On Thursday night I saw Professor Jordan Peterson speak at the Melbourne Recital Centre for the Melbourne leg of his tour promoting his book 12 Rules For Life. The punters crowding the foyer were of a refreshing sort compared to the usual attendees I see at classical music concerts at the venue – generally unattractive people speaking to each other in poor affectations of the British upper class.. Instead I saw confident looking young people with about a 70:30 ratio of men to women.

Antifa were nowhere to be seen. I assume the professor lasered them with his eyes before I arrived.

Jordan Peterson entered the stage to a standing ovation, and appeared genuinely humbled. He immediately launched into exploring an extremely important question: Does he believes in God? He said it was a question he hadn’t answered before, so I found it quite telling that he chose to address it: He obviously considers it a very important question and he has taken his time to think it through before answering it. Did he deliberately chose Melbourne, tHe poz capital of Australia, to address it for the first time? We should have asked him.

What follows is my best attempt at summarising his answers. I will do so as accurately, chronologically and succinctly as I can, with the understanding that it will not be a perfect representation of what he said.

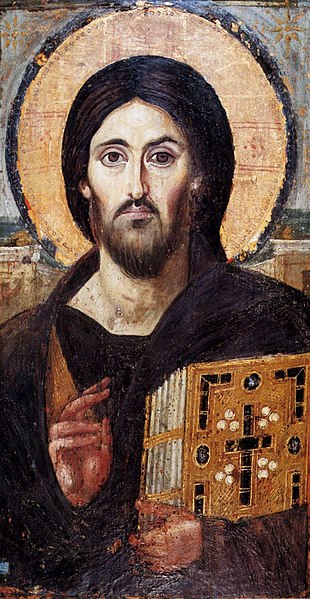

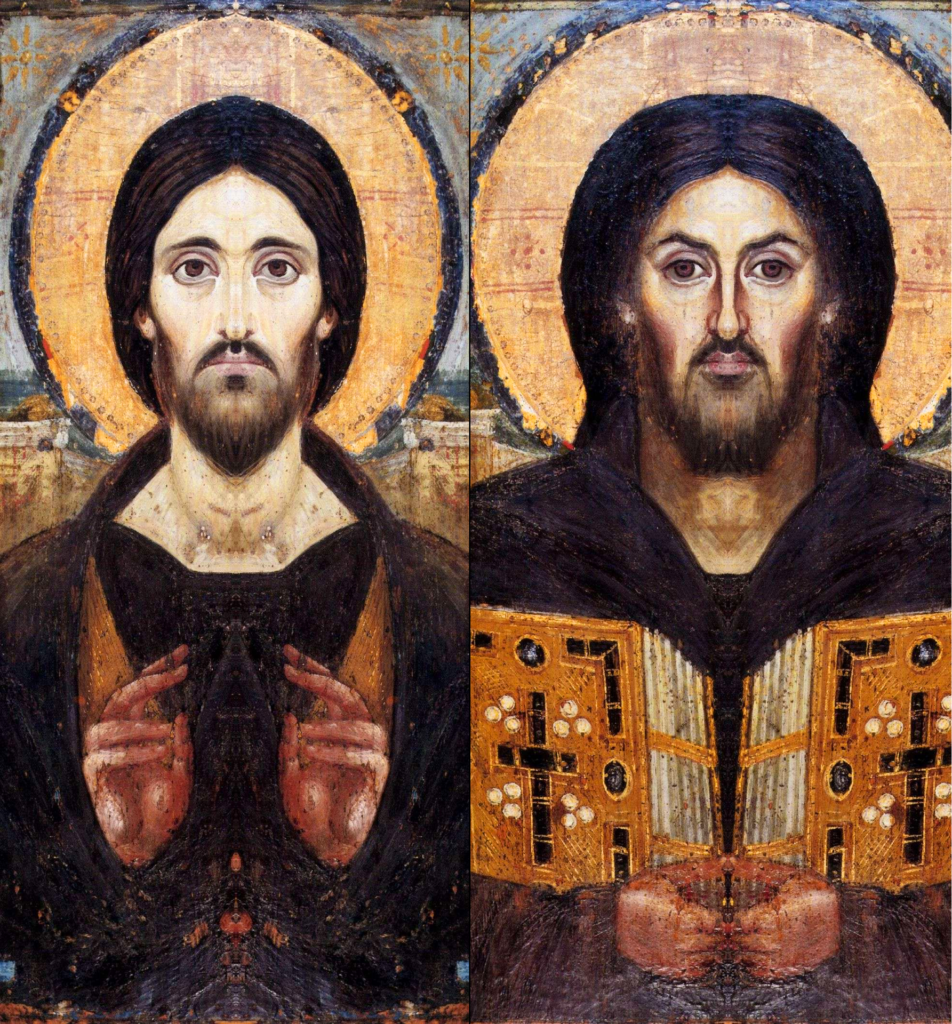

He opened his answer by defining what he means by ‘belief’, and he used two images to illustrate this. The first was the oldest known icon of Christ Pantocrator, believed to have been created in the 6th century AD. Its distinguishing feature is that Christ’s face is asymmetrical:

Here is a mirror image of each side of His face:

This represents the dual nature of Christ, as God and human. He used this to talk about the division in the human brain between left (logic) and right (a connection to the infinite) and in a series of steps discussed the universality of human religious experience, and the fact this experience is easily and readily induced, as evidence for the infinite. You can tell what someone believes by observing their actions; people matter, and our actions should reflect this; heaven and hell are a reflection of the infinite possibilities that exist to choose either good or evil; in this respect heaven could be defined as being a point at the maximum distance from hell.

He prefaced discussion of the second image with the point that there is a price to pay for abandoning meaninglessness. Abandoning meaning gives us the freedom to do whatever we want, but embracing meaning burdens us with responsibility. It means our choices matter.

This second image he chose was of Saint Joseph’s Oratory in Canada.

It is a massive cathedral, built on top of a hill. Miracles are said to have occurred there, and the church itself is littered with the crutches left behind by pilgrims over the last century. There is a staircase leading up to the cathedral, and people experiences suffering ascend this staircase, one step at a time, to get there.

That, he said, was belief; to struggle up the hill under burden, of striving through suffering to reach our aim; to make that aim a point which is heaven, the maximal distance from hell, by making choices based on the belief that we as individuals matter, that people matter; that it is our responsibility as individuals who embrace meaning to make good choices and ultimately make the world a better place.

Along the way he discussed the importance of being precise in one’s speech, to aim well in order to hit your target. He referenced experiments into change blindness:

This demonstrate the fact that your values determine what you see in the world, thus in order to improve on problems in your life you must look at your value structure; do what is meaningful, not what is expedient; put yourself together and aim at the best thing you can.

He lambasted relativism with the simple observation that suffering is not an opinion, it is real. He defined hatred as punishing people pointlessly, punishing them for their virtues; thus he defines love as being the opposite of this. And he alluded to Dante’s Divine Comedy, and the necessity of examining the potential for darkness within oneself in order to appreciate the potential for good, ie the process of going through hell in order to reach heaven.

His talk was dense and there is much I have omitted. It is the kind of lecture one meditates on for a long time, and many essays could be written on one or two points.

He stated that we in the West have become disconnected from our past and in particular our Christian heritage, and we are suffering because of it. He did not explicitly affirm tenets of the Christian creed, but he did his best to make a logical case for them. Tellingly, he argued that accepting meaningless is a bad choice, and the unwillingness to embrace responsibility inherent in this justified unbelief.

Thus, given he presents meaning and responsibilty as good (although difficult) things to embrace, he is justifying belief in God.

Importantly, he kept his analysis for the entire evening at the level of the individual and advocated for achieving a better world through the improvement of decision making by idividuals – stop making decisions which make things worse – and he focused his discussion of belief in God on the level of the individual.

The talk itself was excellent. The Q&A was something else. Usually this part of an event makes me cringe, but my fellow Melbournians served up the most intelligent questions I have ever heard. Hold the nukes.

Ok, so there was the guy who asked Jordan Peterson what he thought of the fact that he is in an open relationship (I know, libertarians) to which the professor asked him:

“How old are you?”

“26.”

“Do you have children?”

“No.”

“There’s your answer.”

In essence, marriage is for the sake of children.

When asked what makes a good leader, he listed five requirements:

- To know where one is going

- To be able to communicate that direction to people

- To be able to bring people on board to his vision

- To have a plan and strategy to get to the destination

- To see it through to the end

He was asked what advice he has for young people in the education system who are trying to push back against Cultural Marxism:

- Remember you are in a war

- Pick your battles so you don’t unnecessarily sacrifice yourself

- Take a long term approach, a decades long approach

The two big ones he was asked were on South Africa and Christianity. Regarding South Africa, he was asked, given how dire the situation is there, is it not time to move past focusing on the individual and to stand up for group identity – for white South African identity?

It is here that I keep in mind Peterson’s story of how he could not bring himself to say things he did not believe to be true. This topic seemed to be the one where he took the most care in choosing his words, to the point of agonising over them. He stated that if there is a gun to your head, then obviously you are out of options, but he reaffirmed the principle that in order to improve the world and to solve conflict we should keep our focus on the individual, to make the world a better place by stopping making choices that will make things worse.

What I took this to mean was that there may be a point in the future, if direct slaughter of white people based on their identity is initiated, that there will come a time to intervene on behalf of a group – white South Africans – in order to stop a genocide.

If that is indeed what he meant, (I am wary here of doing a Cathy Newman and reframing his answers to suit my own understanding of the world) then it is here that I differ from Peterson. The time to intervene is now. The time to wield identity politics is now. The foundations for white genocide are already well advanced in South Africa. If we wait until the second last stage of genocide – extermination – it will be too late.

The country would have already been destroyed.

It is a liberal principle that embracing group identity leads to conflict, the most extreme result being genocide. Aside from the fact that this is a false dichotomy imposed on our minds by our Cultural Marxist overseers, if we fail to embrace group identity while our opponents embrace it, we will cease to exist, without firing a shot. Conflict is what will save us.

I make a similar case here to the case I make against Going Galt. If we rule out the use of force against a socialist system brought about by “democratic” means, and instead work to hasten the destructive effects of socialism by removing ourselves frôm it in order to bring down that system, we cause far more damage – the complete destruction of a country – than if we had been prepared to use force earlier.

On Christianity, Jordan Peterson was direct and assured. He was asked – given that he identified the source of the West’s malaise as the fact that we have been detached from our past, from our Christian heritage – whether we needed a Christian revolution or revival in the West.

He responded very clearly and simply in the affirmative.

The question I have been discussing with friends in the last couple of days is: Is Jordan Peterson a Christian? As I mentioned earlier, he didn’t explicitly state ‘I believe in these tenets of the Cristian creed’ or ‘I have invited Jesus into my heart as my Lord and saviour’. However, he presented a systematic case for the existence of the supernatural, the infinite; for understanding the nature of belief, of heavan and hell, sin, good and evil, love and hate; and he repeatedly affirmed that the West needs to reconnect with its Christian roots. He also referenced several readings from scripture in his talk, and attempted to discover the truth in these passages.

Given that he has dedicated himself to spreading this pro-Christian message across the West; given he states that you can deduce the value system of an indiviual by observing their actions; indeed given that the Bible states “You will know them by their fruits”; I conclude that Jordan Peterson is a Christian.

However, I understand that “do you believe in God” and “are you a Christian” are two different questions. If Jordan Peterson ever chooses to answer the latter, I would very much like to listen.