Nathaniel Lucas

The writer Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad (V.S.) Naipaul died last Sunday, Australian time. The author of nearly thirty books, Naipaul won almost every major literary award in the English-speaking world as well as the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001. He was born in Trinidad, an island at the bottom of the Caribbean Sea, at the mouth of Venezuela’s Orinoco River, in 1932. His family were descended from Indian peasants who had been brought to Trinidad by the British in the nineteenth century to work sugar cane plantations. By his father, who read Dickens and Thackeray and had thwarted literary ambitions of his own, Naipaul, received an English idea of education and ended up at Oxford on a scholarship in 1950. In 1961 his novel A House for Mr. Biswas, a sort of comedic Caribbean East of Eden, was published, confirming Naipaul in his vocation. After Biswas he set out writing travelogues of India, the Caribbean, Africa, the U.S.A. and the Islamic world.

Naipaul was one of the major implicitly illiberal writers of our time. The opening line of his novel of post-colonial Africa, A Bend in the River (1979), is a succinct summary of his worldview:

“The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.”

Both in fiction and non-fiction, which he wrote in roughly equal measure, he chronicled newly independent third world nations in an increasingly confused and accelerating world. He was an observer of the shadow thesis of post-colonialism: that the newly independent nations of the third world had merely traded their old masters for new ones, either local tyrants, pseudo-Marxist megalomaniacs or the American State Department. Rather than entering a new phase of nationhood with dignity and mastery over their own circumstances, the third world nations were being ruled by proxy, descending further into despair and chaos and squandering the things—roads, institutions, legal systems—that the Europeans had left behind.

But Naipaul, as he often said in his travel books, had no political system of his own. When he visited a country he had no fixed plan. He would follow his interests and his instincts and arrange to talk with prominent as well as everyday people. He allows dialogue to speak for itself. He is especially sceptical of those with utopian political projects. Every aspect of society comes under his purview—advertisements, roads, newspapers, the interactions of strangers in bars. Often his travelogues are stories of failure—to reach a certain destination, to speak with a certain person, to come to an understanding—Naipaul admits when he has found nothing.

Despite his often forceful judgments he was profoundly sensitive to the societies in which he travelled. Seeking an audience with a particularly holy cleric in the holy city of Qom, Iran in the holy month of Ramadan, in the holy revolutionary year of 1979, Naipaul and his guide puzzle out how to present the strange foreign writer. He cannot say he is a Christian or an atheist. Hindu—pagan—is utterly out of the question.

“Bezhad said, ‘How shall I introduce you? Correspondent? Khalkhalli likes correspondents.’

’That isn’t how I want to talk to him, though. I really just want to chat with him. I want to understand how he became what he is.’

’I’ll say you are a writer. Where shall I say you come from?’

That was a problem. England would be truest, but would be misleading. Trinidad would be mystifying and equally misleading. South America was a possibility but the associations were wrong.

’Can you say I am from the Americas? Would that make sense in Persian?’

Bezhad said, ‘I will say that you come from America, but you are not American.’”

Naipaul was keenly attuned to the subtleties of race and class and totally devoid of liberal sentimentality in such matters. About the third world he was totally unromantic. Where others saw noble poverty or squalid beauty, Naipaul saw petty cruelty, mendacity, disorder and absolute desperation. Predictably, he was accused of all the contemporary sins, racism, misogyny, Western chauvinism, and endured a number of spats with writers and academics incredulous at his class treachery. The famous academic turgitator Edward Said said that Naipaul “allowed himself quite consciously to be turned into a witness for the Western prosecution”. He was probably among the last of writers who could have gotten away with the things he said. Being a colonial himself probably helped him, but the genteel left of the 1960s and 70s piled on when he wrote about things such as the stench of Indian cities or gratuitous cruelty to animals in Africa, or the insularity and magical thinking of the Islamic hardline in Iran.

Among modern novelists few have depicted third world resentment as accurately as Naipaul. Resentment (the French ressentiment is perhaps more accurate, more resonant, less personal, more civilisational)—of men by women, of the first world by the third, of the rich by the poor—drives much of modern political discussion (debate is no longer an accurate word to describe this phenomenon). Contemporary social justice emerged in part out of the former European colonies in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Naipaul chronicled the grotesque “mimicry” of Western forms by disgruntled ex-colonials, frustrated revolutions and failed projects of self-aggrandisement. Just as contemporary social justice warriors lack understanding of how the industrial world of mass prosperity was created, and by whom, Naipaul’s would-be revolutionaries, both in his fiction and non-fiction, have a dim understanding of European success. They feel victimised and doubly so. They want the conveniences and glamour and beauty of Europe without understanding how those things were made, and despise themselves for wanting them. The inadequacy of their own culture is obvious but to admit this is impermissible to the post-colonial psyche. They have a taste of Western education, just enough to be dangerous, as the saying goes. And dangerous they are.

Like all disillusioned children, discovering their parents’ weakness, they resent the current diffidence of the West. We lost to these people?, they ask and feel insulted. The point is not to gloat at Western superiority, but to recognise the danger an untethered resentful population poses to Western stability and cohesion.

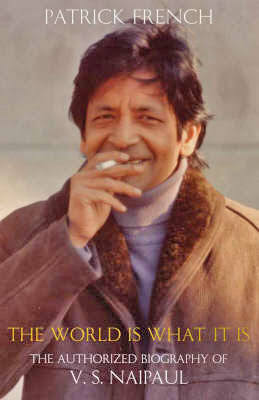

But Naipaul was just as unsparing on himself. In The World Is What It Is (2008), his biographer Patrick French included many details about his affairs, brothel visits, and physical and psychological cruelty to his first wife and his long-term mistress. French sent the draft to Naipaul to be amended in accordance with an agreement they had made so the book could be authorised. It was returned to him unchanged. Naipaul’s ego was perhaps monstrous and outsized. He didn’t care that the world saw his failings, but the story also shows his absolute faith in honesty.

The left-liberal press, in its impregnable confusion, will call Naipaul’s writing about race and the third world, the acidity of his judgements and the beauty of his words, contradictions. But in truth he was remarkably consistent. His schema of value was idiosyncratic but he applied it evenly. Although he was not explicit about his beliefs, he was something of a Western chauvinist. The achievements of Europe and Europeans abroad, and those societies that plausibly maintained European notions of order and enquiry, and had given him and his father their idea of an intellectual life, were to him the highest.

Interested readers should start with A Bend in the River, for fiction, and Finding the Centre, which contains two long essays, one autobiographical about his origins in Trinidad and the other a characteristically foreboding and futile excursion through the newly independent Ivory Coast, for non-fiction. The best of him, as he said, is in his books. The world is bereft of honest observers. We can’t afford to lose more like him. RIP.