Over the last few days, the Australian Government’s campaign to address domestic violence has been plastered throughout our local media. The campaign ads at this point focus on domestic violence perpetrated against women, by their male partners.

Combined with the government’s new campaign, we are told almost every day of the epidemic rates of police call-outs relating to domestic violence, and we are reminded of the horrific number of women killed by their (male) partners each year. It will be interesting to see how much impact this approach to address the problem will have on the rates of family violence in the community.

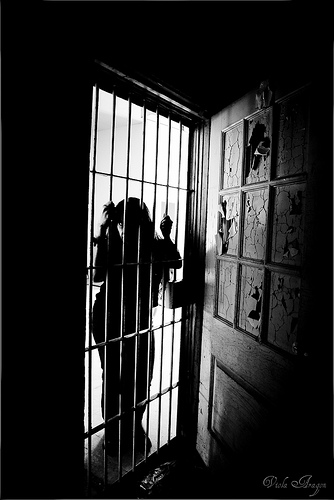

Yet, when it comes to overall instances of domestic violence, a significant part of the problem is invariably left out.

A case in point was illustrated today when the Victorian Supreme Court set free a mother who stabbed her partner to death. The woman pleaded guilty to manslaughter after killing her partner with a broken piece of glass. We are told that it was a violent relationship, and that the woman had killed her partner after he had assaulted her. The court sentenced the woman to 18 months time already served and a community corrections order.

Can we imagine if this situation was reversed, and a man who killed his partner, pleads guilty and is then set free by the court? Not likely. Furthermore, if the woman set free by the court had been a man, can you imagine the outcry we would now be hearing?

Unfortunately, this particular instance of family violence is not simply a matter of the lighter sentences which are generally given to women, compared to men, for the same crime. Rather, it goes to the heart of how domestic violence campaigns have to a large extent become distorted and selective in their focus.

A further point which illustrates the way the issue of family violence has become distorted can be seen with the campaigns of 2015 Australian of the Year, Rosie Batty. Batty used the killing of her son by her mentally disturbed former partner as the basis of her campaign; a campaign, not calling for an end to violence against children, or family violence in general, but a campaign which was overwhelmingly focused on addressing violence against women.

While Batty would probably claim that her campaign was about addressing all forms of family violence, the reality is that her campaign and the speeches she delivered focused almost exclusively on violence committed against women, and not on violence committed against children or other forms of domestic violence.

Unfortunately, family violence campaigns like Batty’s (and now the Australian Government’s) persist in failing to address adequately issues like the unacceptably high number of children killed or abused by their mothers, or who die as a result of neglect. These victims of family violence are not given a voice, and are abandoned in favour of a more ideologically based narrative.

While family violence campaigns continue to be couched in vague terms such as ‘equality’ and persist in being founded on the basis of feminist and other theories of oppression rather than the perpetration and causes of actual violence, we will continue to fail to properly address the very real problem of family violence in our community.