Originally published May 19, 2020. Since publication the trade war and war of words between Australia and China has only intensified. As such the argument made here only becomes more relevant. If Australia is full of foreigners and our political system is founded on multiculturalism – favouring foreigners over the Australian people – our traditional understanding of foreign relations becomes meaningless.

Australia pushes for an investigation into the outbreak of the Chinese Diversity Flu. China responds with an 80% tariff on Australian barley, restricts beef imports and threatens our tourism, education and wine sector. Multiple countries rally to Australia’s side to support said enquiry, China backs down and says it will support an investigation and even acknowledges concerns with regards to its wetmarkets.

Yay we won or something.

Aside from the fact that they don’t appear to be backing down on the whole trade war thing just yet, there is something I can’t quite put my finger on.

Chris Kenny has given us some solid analysis, pointing out that Federal Labor, Labor state governments, some unions and some business leaders are undermining the government’s response to China, openly collaborating with the Chinese and defending their own business links to China, in part as a Cold War hangover and continuation of the so-called “cultural cringe”.

Cultural. There is something about that term.

Greg Sheridan points out that criticising the Australian government for being at odds with the Chinese government displays an ignorance of how the Chinese government operates. If the Chinese government is displeased with you, all it means is that the Chinese government wants something from you.

But I am trying to remember what the difference between Australia and China was in the first place.

Social media has lit up at George Christienson’s suggestion that the Australian government nationalise the Port of Darwin as a first step towards taking back vital infrastructure from foreign ownership.

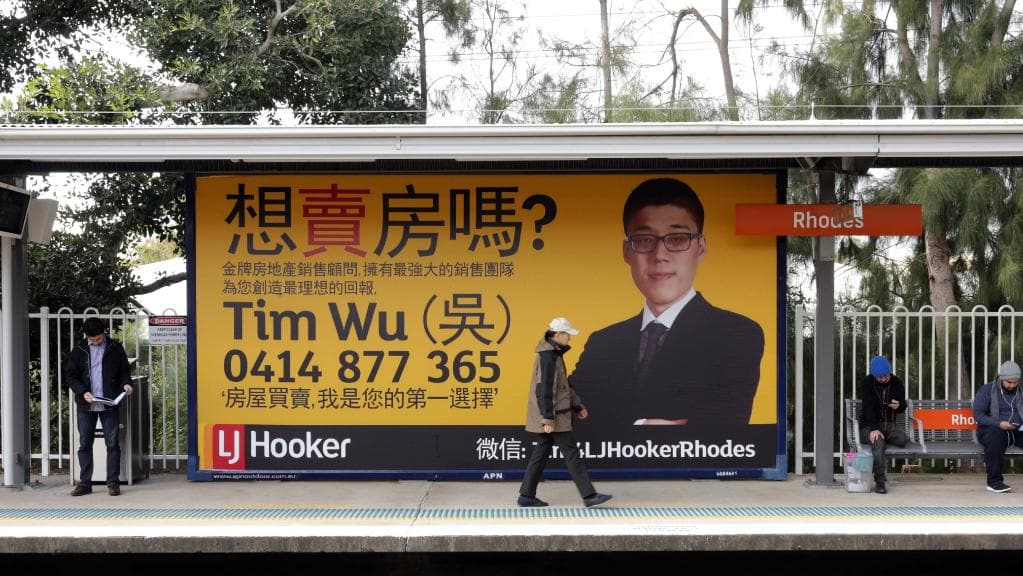

It is vital that we prevent foreigners from overseas buying up Australia so that the foreigners already here can buy up Australia.

We’re starting to get a picture here. Let’s return to Chris Kenny’s analysis:

“Now, we can see the Cold War hangover but it is infused with a dose of 21st-century identity politics. This is the self-loathing of those who prefer shame about a white, Christian and Anglo nation in the wrong place at the wrong time, rather than pride in a multicultural success story, founded through British institutions in a land of indigenous heritage, that helps to forge a better world.”

Kenny’s point here seems to be that Australia’s self-loathing classes cannot accept the fact that they won. Real Australians are indeed white, Christian and Anglo but Australia is no longer a white, Christian or Anglo country.

Multiculturalism is not a success for Australia or Australians. It has however successfully turned the homeland of Australians into a multiracial economic zone, in which multiple races are encamped sharing an uneasy peace. This economic zone is mostly still led (nominally) by Australians, but they hold their positions on the understanding that they must never advocate for the interests of Real Australians.

If this looming trade war was to escalate and Australia’s government was overthrown in a Chinese invasion, Australia’s government would not become any less anti-white, anti-Christian or anti-Anglo. It would simply turn its favour from every other non-Australian race of people that lives here towards one, the Chinese.

It is in this context that our traditional understanding of International Relations becomes meaningless. There is no longer an Australia to speak of. Australians are a people but Australia is not a country. Our task as Australians is to continue to advocate for the political interests of Australians, while working to ensure that our people survive whether or not we hold political power.