Eric Louw

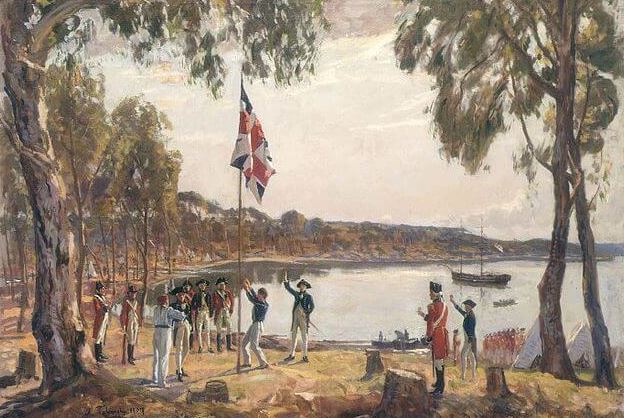

In 1788 the British established the Colony of New South Wales when the First Fleet landed a party of convicts, marines and officials at Sydney Cove.

In dispatching these settlers to Australia, Britain was following a long-established human tradition of founding colonies on distant shores.

The ancient Greeks and Phoenicians had established colonies all around the Mediterranean. The Romans replicated the Greek model when setting up colonial settlements across Europe and North Africa.

And of course, the English nation itself emerged as the result of Saxons, Angles and Jutes sailing across the North Sea to establish colonial settlements on the British Isles.

Australia was born out of Britain’s move into the Indian Ocean region during the 1600s to search for spices and to build Europe-to-Asia trade routes.

After initially focussing on Indian trade. The British went on to expand their interests across the entire Indian Ocean region from Cape Town in the west to Perth in the east.

British settlers moved to many new colonial cities that Britain founded across the region, like Adelaide, Durban, Bombay, Calcutta and Singapore.

Importantly for us, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the British founded six Australasian colonies in New South Wales, Tasmania, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and New Zealand. These were Pax Britannica exercises in colonial settlement.

When the colonial model is deployed, settlers take their old culture with them and plant this culture in a new place. So Pax Britannica colonies were deliberately created to replicate the culture of Britain – they were designed as “overseas” colonies, where copies of home were built in new places.

The six Australasian colonies were an exercise geared to building a New Britain on the other side of the world. Importantly, colonists are not migrants.

Colonists do not have to adapt to new cultures because they carry their culture with them to a new society that is built to be the same as the society they left behind.

Colonists may have to adjust to new climates, vegetations and geographies, but they do not have to adjust or assimilate into an unfamiliar culture.

Colonists do not leave their old homes with the expectation that they will need to abandon their existing cultures in their new homes.

This is because they are simply moving from one part of the empire to another part of the same empire, and in the case of the British Empire, Boston, Sydney, Toronto, Auckland and Durban were as much British cities as was London.

So colonisation is not the same experience as migration because English colonists systematically recreated their old Anglo social worlds across the seas in far-away colonies like Massachusetts, Virginia, Ontario, New South Wales and South Australia.

Hence whereas migrants do have to abandon their old cultures and adjust to/assimilate into the culture of a new society, colonists did not have to experience the pain of migrating into a new culture.

Today’s advocates of globalism, multiculturalism and mass migration love to claim Australia is a “migrant nation”.

This is at best a partial truth because the designation “migrant nation” really only (partially) applies to post-1990s Australia.

In truth Australia is more accurately described as a “colonial nation” or “settler nation”. Of course it is true that some migrants did come to colonial Australia.

Prussians migrated to South Australia in the 1830s and 1840s. Italians migrated to Queensland in the 1930s.

Europeans displaced by World War II were recruited as migrants in the 1950s. But these were never mass migration phenomena of the sort we have seen since the 1990s.

So these European migrants were simply absorbed into the overwhelmingly dominant Anglo society that had been born out of the British colonial-settler experience of the nineteenth century.

Even after the past three decades of mass migration into Australia, most Australians still do not trace their ancestry to migrants (in contradistinction to the propagandistic hype of the globalist multiculturalists).

Instead, a majority of Australians can still trace their roots to the British Isles.

The bulk of Australians remain descendants of Anglos from one of two sources.

They either moved directly to Australia as colonists during the Pax Britannica era, or they came to Australia via one of the other parts of the Pax Britannica after the demise of the British Empire (such as New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Rhodesia, British-India or British Malaya).

As late as the 1960s Australia was still importing Anglo settlers (not migrants) as part of what were effectively Anglo-colonization schemes such as the “Ten Pound Pom” scheme (1940s and 1950s) or the “Bring out a Briton” scheme (1950s and 1960s).

Consequently, it is more correct to call Australia a “colonial nation” rather than to call it a “migrant nation”.

There is, however, always the danger that this might change in the future if Australia is foolish enough to continue importing millions of culturally non-proximate migrants through mass migration of the sort we have seen since the 1990s.

So when did Australia shift from a colonial settler model to a migrant model?

Although there is no exact date, broadly the beginning of this shift can be traced to the 1960s.

What is more, the origins of this shift seem to have everything to do with the way the Pax Americana replaced the Pax Britannica.

The Suez crisis marked the moment when Washington informed Britain that henceforth London had to accept the dominance of the Pax Americana.

This shift naturally impacted Australia as well. As a creation of the British Empire, Australia had always followed London’s lead.

Unsurprisingly, this meant Australia looked to Britain for its settlers. Hence during the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s Canberra looked to Britain as its primary source of settlers within a policy framework that mixed the old colonial-settler model with a new migration model.

The mix reflected that transfer of power from London to Washington that Australia was having to adjust to in the 1950s.

Effectively we saw Canberra learn to follow Washington’s lead instead of London’s lead. Whereas before the mid-1950s Australian policy-making had a distinctly British feel, after the mid-1960s Australian policy-making acquired an American feel.

Amongst the changes was Canberra’s shift towards US-style migration policies and an abandonment of the British colonial model (as seen in the “Ten Pound Pom” and “Bring out a Briton” schemes.

As it turns out, Canberra’s realignment towards American-style immigration policy occurred just after the USA revised its own migration policies with the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act.

This new American immigration policy encoded the impact of the civil rights movement and the new mood of the Kennedy administration’s leftist non-racially discriminatory ‘progressivism’.

Importantly, this 1965 Act removed from America’s migration policy the 1920 National Origins Formula which had sought to preserve America’s existing culture by promoting immigration from culturally-proximate western and northern European nations.

At the same time, it discouraged immigration from the non-culturally proximate peoples of southern Europe, eastern Europe and Asia.

And so Canberra’s 1960s realignment towards American-style immigration policies ended up encoding into Australia’s new migration policy the Kennedy administration’s progressivist bent towards non-discriminatory immigration.

For Australia this involved a big shift away from the British colonialist model towards the deliberate importation of culturally non-proximate people in order to virtue-signal to the world that Australia was not a racist nation.

Unsurprisingly, accompanying this new virtue signalling approach to migration was the promotion of the ideologies of multiculturalism and anti-racism.

The impacts of this were, of course, profound. Once migrants were not selected for cultural proximity to Australia’s Anglo culture, then a shift occurred towards cultural diversity.

Over time such a shift would necessarily erase the Anglo-Australian society that had been created by the Pax Britannica.

This represents a profound change and yet curiously Australian politicians never deemed it a good idea to have Australians debate whether they wanted such a change.

Seems to be the time has come to have such a debate because the adoption of American-style migration policies in the 1960s became a problem when combined with post-1990s mass immigration into Australia.

The small- scale arrival of non-culturally proximate immigrants is not a problem because small numbers can be assimilated.

But when large numbers arrive through mass migration programs such assimilation no longer happen.

That in turn produces uber cultural diversity that lends itself to social conflict. It is time to debate to what extent Anglo-Australian culture is threatened by the following:

- Australian migration policies have adopted and internalized the guiding spirit of America’s 1965 Immigration Act and the ideology of multiculturalism.

- Australia has adopted the idea that there is no danger in encouraging the mass immigration of people who are culturally non-proximate to our Anglo-Australian culture. This idea and the policies built upon it seem naïve.

- What are the dangers of adopting multiculturalism which allows huge numbers of culturally non-proximate people to both migrate and to keep their original cultures? Does this create cultural Balkanization and the potential of future social conflict?

- The dangers of copying USA migration-type policies; plus adopting mass migration and multiculturalism are greatly exacerbated by also importing and adopting the products of USA universities like Critical Race Theory; DEI and other Woke thinking. (There is no reason for Australians to adopt American guilt which underpins CRT, DEI, etcetera).

We are a colonial nation (not a migrant nation) and should be proud of it.

We should celebrate our colonial past and reject the propaganda of leftists, globalists and advocates for mass migration who tell us that our British Empire colonial legacy is bad.

Australia is the outcome of one of the most successful colonial projects in history. We should be proud of this and teach our colonial history with pride in our schools.

Originally published at Richardson Post.