South Africa’s Brave New World: The beloved country since the end of Apartheid, is a political history of South Africa from 1994 – 2009. I’m a bit late to the party with this book having first been published back in 2009, but it has some very interesting information and insights. Normally a reviewer talks about the good, then the bad but I think I’m going to start with the bad, then move on to the good and finish with some minor criticisms.

South Africa’s Brave New World: The beloved country since the end of Apartheid, is a political history of South Africa from 1994 – 2009. I’m a bit late to the party with this book having first been published back in 2009, but it has some very interesting information and insights. Normally a reviewer talks about the good, then the bad but I think I’m going to start with the bad, then move on to the good and finish with some minor criticisms.

The book is far too long, it could have conveyed much of the same information in half the pages and the main reason that it goes on is because it is disorganised. I was interested in what befell the police and the army after Apartheid and he [R. W. Johnson] does talk about these things. But as short detours in the middle of chapters that are quite large, unfortunately this is a recurring theme. The book could have really used a Dramatis Personae or list of characters. So many names are mentioned, who then reappear chapters later in a new job, it is very confusing and could have been done better.

The glossary at the start of the book, where all glossaries should be, was a big help.

I actually think that this book provided a good deal of insight into South Africa, the ANC and the period of ANC rule up until 2009. One insight that I found interesting is his assertion that South Africa has since independence in 1910 been ruled by a Nationalist ideology. The first from 1910-1947 was British Empire loyalty, the idea that South Africa was British or in South African terminology ‘English’. Which was replaced between 1947-1990 with an Afrikaner nationalism, that replaced loyalty to the Empire to one of loyalty to Volk, particularly the Afrikaner Volk. Which in turn was replaced in 1994 with a Black African nationalism, which continues. The period between 1990-94 was one where much of the Afrikaner nationalism was being dismantled. It is an interesting idea that the current government is more of a continuation than a new start.

He also writes about the different factions within the ANC that made up the first government in 1994. The smallest but most prestigious were the prisoners like Mandela, the second largest were the Exiles, who had lived outside of South Africa. Most of these were Communists who believed in the revolution and in the inevitable destruction of Capitalism. The largest group by far, but at the same time the least prestigious as well as the least influential were the Inxiles, who had remained in South Africa. It was to be the Exiles who benefited the most from the end of Apartheid. They were organised and unlike the Inxiles disciplined enough to take control of most of the senior government positions as well as those in the ANC. In effect the Inxiles were frozen out of the victory that they had struggled for.

My favourite subtitle heading in the book is ‘Crony Capitalism for the Comrades’ as it sums up in one little phrase what happened when Communists realised that they could be rich.

Because now that they were back in South Africa they did realise that now was the time to make up for the personal sacrifices that they had made. It also helped that they had seized the commanding heights of the government and the ANC. Which means that much of the history since 1994 has been the efforts of the Exiles to consolidate their position, not just in politics but in money. BEE (Black Economic Empowerment) was meant to be a way for Blacks to get a foothold on the economic ladder. Companies would need Blacks to in effect ‘legitimise’ them. Which meant that the companies wanted the most powerful and connected Blacks, people like the Exiles. Which came to mean that in reality BEE helped a few hundred families in a country of about 50 million people.

The author is scathing in his criticism of BEE and Affirmative Action, I don’t recall him having anything good to say about them. The ANC is not far behind in his criticism. He regards Mandela as a popular non-entity, a man who came to power when he was too old to influence events. To be fair he did influence the peaceful transfer of power and he did believe in the ‘rainbow nation’. Most of his contempt is directed towards Zuma, both as Vice President and as President. He blames him for much of the mismanagement that occurred during those 15 years and while I don’t disagree with him. I do feel that the ANC and its structure is the real issue that has not been addressed and maybe never will be.

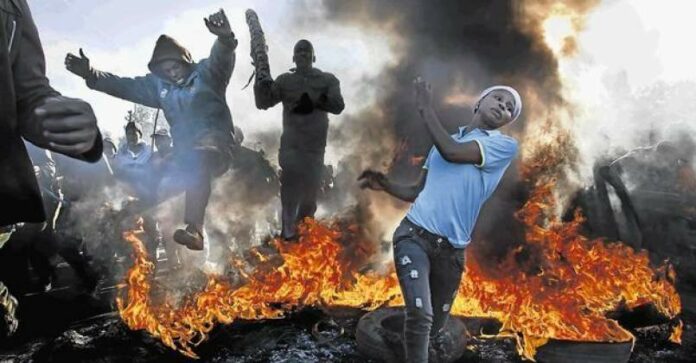

What I find interesting is that he is a Liberal and the Liberal promise of the end of Apartheid was that non-Whites would get to live the lives that Whites enjoyed. It was not that a new select group would arise and take the place of Apartheid, or that Apartheid in a new form would be enacted. But he realises that that is exactly what has happened. He also writes about how galling it has been to see the future that he wanted for South Africa not appear but that the ‘racists’ as he calls them were right. South Africa has become a richer version of the rest of Black Africa, a kleptocracy where theft is the reason that you go into government, mismanagement and race baiting.

Part of the problem is that as a Liberal he keeps trying to be race blind and it is interesting to see him struggle with what he believes and what he can see with his own eyes. Africa is not just a product of its past but also of its present. The civilization that covers the world is not African, it’s European, which means that they are trying to govern under the rules of someone else’s civilization. The truth is that if South Africa was an all White country, it would be a lot more successful than if it was an all Black country, even if those Blacks were of the same ethnic group.

I want to leave you with an excerpt from the book about his attending an Anti-Racism conference in South Africa, September 2001, (p.350):

‘Indigenous people’ were invited from all over the world and the cause of ethnic minorities anywhere in the West was taken up with great indignation. Arriving in Durban for the conference, I found what could only be described as a crazed millenarian expectation and furious blaming. Black Americans, Roma, Inuit and many other minorities were there in strength and were all, apparently, angry. Even many of the whites attending the conference were anti-white. A great theme was the rights of indigenous peoples but this did not seem to work at all. Thus whites were condemned for colonialism abroad, and were also blamed for not making ex-colonial people welcome enough in their own countries. I asked many delegates whether there was anywhere that whites had rights as indigenous people themselves. There was apparently no such place.

Originally published at Upon Hope. You can find Mark’s Subscribesstar here.