From Patriotic Alternative.

From Patriotic Alternative.

Johnny Alba

When you look at the recent history of the United Kingdom with COVID restrictions, years of austerity, falling living standards etc it is easy to forget that the people of our nation once had a proud history of rebellion against authority and perceived injustices.

Today we seem more than happy to put up with restrictions on our liberty, our jobs being taken away by offshoring or automation, rising taxes and many other things without a murmur of protest. But it was not always that way and one such occasion when the Scottish people rose against authority was the Radical War, also known as the Scottish insurrection of 1820.

For many years leading up to 1820 unhappiness at the current situation in regards to voting rights, pay and work amongst the working classes in Scotland had been on the rise. Scotland had at this time one of the most educated working classes anywhere in the world. This is due to many factors, one being that a lot of the skilled tradesmen at that time worked on commission and were free to set their hours. This allowed many of them to spend time reading and debating with other workers who had been similarly spending their time. The Church of Scotland had a long tradition of encouraging education and also of supporting and encouraging the rights of individuals. So many new and at the time radical ideas spread quickly amongst the working classes of Scotland.

Around this time the world had been shaken by a series of events that saw the working man stand up against authority and win with both the American and French revolutions taking place. These events encouraged many people to support the Radical movement, an early precursor to what sadly became the modern scourges of society Liberalism and Progressivism. One of the main complaints of the Radicals was that in Scotland only one in 250 people had the right to vote. A situation that was of course very wrong, though when you look at the decisions of the voting public today one may wonder if creating universal suffrage wasn’t that good an idea in the end of the day.

Towards the end of the 18th century, there were organisations such as the Scottish Society of the friends of the people and the Society of the United Scotsmen agitating for parliamentary reforms. Though in most cases their activities were short-lived as they were harshly repressed by the Government with many of the leading agitators sentenced to transportation to Britain’s then colonies.

Economic depression

Events would eventually come to a head after the end of the Napoleonic wars when the United Kingdom experienced a period of economic depression. Many workers were experiencing the negative effects of the industrial revolution with the loss of many jobs and falling wages. A situation made worse by the ongoing existence of legislation such as the corn laws that led to very high food prices and of course the lack of representation of the working classes in the parliamentary system was an ongoing gripe.

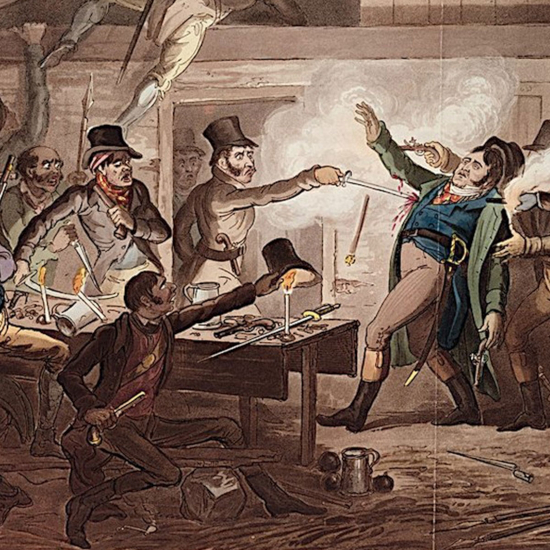

The Peterloo massacre of 1819 caused widespread protests across Scotland with meetings held in Stirling, Airdrie, Fife, Renfrewshire, Dundee and a memorial event in Paisley ending in rioting and the use of Cavalry against the Workers. The political class and gentry were startled by these events and started to see the spectre of revolution hang over the United Kingdom. They quickly moved to raise volunteer regiments to protect their interests. The action, which became known as the Cato Street conspiracy, to murder the Prime minister and all the British cabinet ministers at the start of 1820 led to further waves of repression across the country.

At the same time, the so-called Radicals became more organised forming a 28 man committee to form a provisional government and arranging military training for their supporters. Though the committee was short-lived when they held a meeting in Glasgow on the 21st of March 1820 all of them except a weaver named John King who left the meeting early were arrested. A second meeting occurred a day later on the 22nd and the attendees were told that an uprising was imminent and that they should be prepared for it. The following day a further meeting was held on Glasgow Green and then at Rutherglen close by where they unveiled plans to form a provisional government and showed the draft of a proclamation to such an end that they were to have printed. They also exhorted their followers to make pikes for the upcoming uprising.

Proclamation

A few days later on the 2nd of April, the proclamation was displayed throughout Glasgow. It read

“Friends and Countrymen! Rouse from that torpid state in which we have sunk for so many years, we are at length compelled from the extremity of our sufferings, and the contempt heaped upon our petitions for redress, to assert our rights at the hazard of our lives.” by “taking up arms for the redress of our common grievances”.

“Equality of rights (not of property)… Liberty or Death is our motto, and we have sworn to return home in triumph – or return no more…. we earnestly request all to desist from their labour from and after this day, the first of April in possession of those rights…”

It called for a rising “To show the world that we are not that lawless, sanguinary rabble which our oppressors would persuade the higher circles we are but a brave and generous people determined to be free. ”

A footnote added: “Britons – God – Justice – the wish of all good men, are with us. Join together and make it one good cause, and the nations of the earth shall hail the day when the Standard of Liberty shall be raised on its native soil.” It was signed by order of the Committee of Organisation for forming a Provisional Government. Glasgow April 1st. 1820.

General strike

On Monday the 3rd of April a general strike began across large areas of central Scotland. Workers carrying out military drills and making weapons were spotted in many areas. Wild rumours spread across the country such as that England was up in arms in favour of reform and that a French army of 50,000 was mustering outside Glasgow commanded by one of the Marshalls of France who was from a refugee Jacobite Family. None of these was true of course but they spurred the workers on. The Government was ready for these actions though with troops prepared and martial law imposed in many areas.

A group of workers attempted to march from Glasgow to the Carron ironworks in Stirlingshire intent on seizing weapons they believed were there but were intercepted by a police patrol and scattered. The next day a group again left Glasgow heading for the ironworks, though part of the group grew dispirited on the march and dropped out. A further small group did join them on the 5th of April as they continued their march to Carron but they had been spotted and reported to the authorities by people they met along the way.

A group of Dragoons and Yeomanry left Perth to defend the ironworks against this ragtag insurgent force. But before reaching it they ran into the radicals just outside Bonnybridge and the radicals opened fire on them, the Government troops returned fire and a small skirmish entailed. The workers were no match for the troops and soon they were overpowered. Nineteen men were captured and taken to Stirling Castle to be imprisoned. The army stood on high alert expecting more unrest in the Glasgow area but it failed to materialise. Some small disturbances did take place in other areas such as a government volunteer unit, that had arrested radicals in the Paisley area, was ambushed in Greenock while transporting prisoners and their prisoners released but no large scale uprising occurred as had been promised by the leaders of the radicals.

Punishment

The Radical war was mainly over a few days after the initial proclamation was posted and many young radicals fled the country on ships from Greenock to Canada to avoid arrest. For many, though that was not the end of their struggle for Political reform, one figure who went on to become a leader of the Canadian rebellions of 1837-38 was a Scot called William Lyon Mackenzie

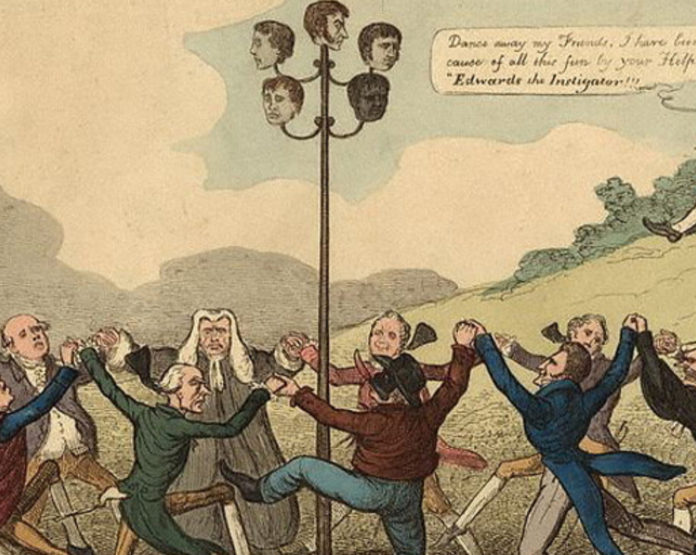

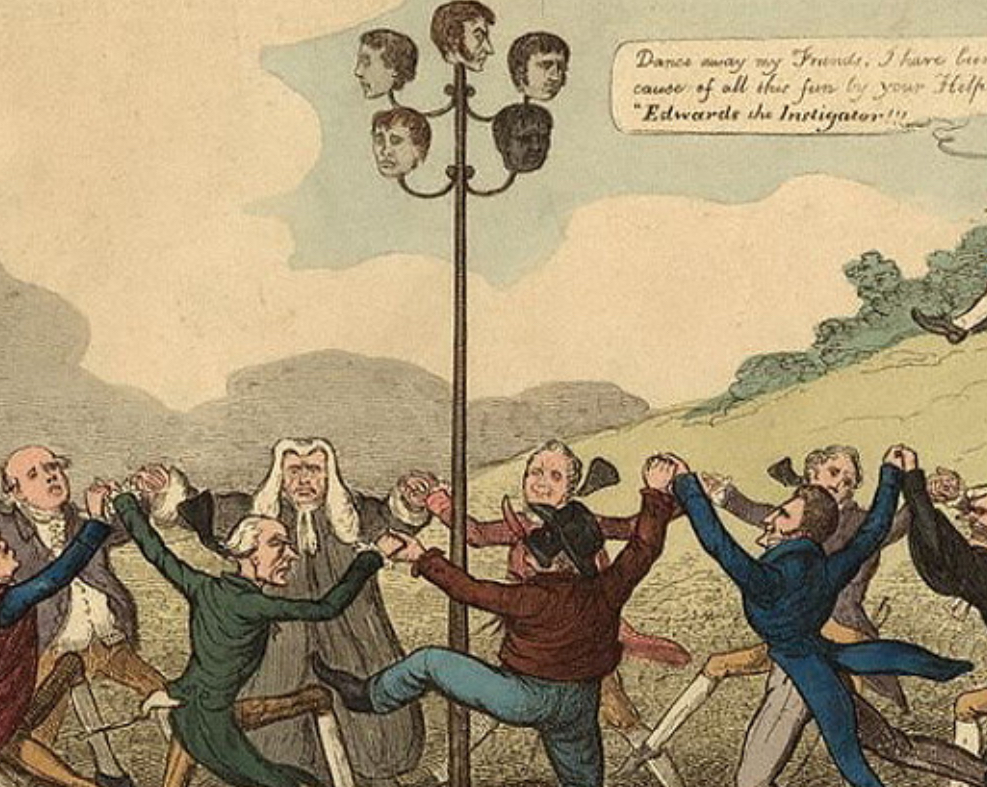

88 men were charged with treason and a few of the ringleaders such as James Wilson, Andrew Hardie and John Baird were executed by hanging and beheading. Hardie and Baird had the dubious honour of being the last victims of beheading in the UK. Others were lucky and were either found not guilty or were discharged, but 18 men were transported to the Australian colonies as punishment for their part in the uprising.

Though ultimately a failure the uprising did add to the pressure for reform which though slow in coming did happen over the subsequent years. Radical unrest did die out for a period in Scotland but the Scots were at that time not ones to cow-tow to authority. In later years such actions as the rent strikes of world war one, the 1911 singer sewing machine factory strike, the strike for the 40-hour working week, the Leith dockers strike, the Timex strike of the 90s and the land raids of the 19th and 20th centuries being just a few examples of the Scots’ spirits to fight for their rights.

Sadly that spirit seems to have been lost of late with the majority happy to sit by as they are told how to live by the government and their quality of life deteriorates. What action there still is, is mostly hijacked by the so-called “socialists”, a situation that we cannot let continue. It is us Nationalists who are the defenders of our people and our nation and we need to step up and lead the way in opposing the ongoing Government infringements on our freedoms and fight for a better standard of living for our people.

The International Socialists of the left have mainly abandoned our people, unless it suits their wider agenda, to fight for the rights of incomers over the indigenous population. But many people still believe the unions and the Labour/ socialist parties to be their friends, they are not. We need to work to make the people of Britain realise this and that it is only the Nationalists of this country who can lead them to a better future.