Originally published March 17, 2018.

If you’ve been on a university campus in the last five years, you won’t have been able to ignore them.

If you’ve ever disagreed with them in person, regardless of whether you’re on the left or the right, you’ve likely never forgotten the experience.

If you’ve ever torn down a poster in disgust and wondered why they seem to coat the inner cities like wallpaper, then most likely you’ve encountered their handiwork.

If you’ve ever tried to hold an event that the left doesn’t like, regardless of whether you’re a sitting senator, an elected representative of an overseas parliament, a local anti-immigration campaigner, someone who disagrees with gay marriage, someone worried about Islam, or even the left-wing sister of a conservative former Prime Minister, then you’ve met them.

In the last case, not only have you met them – it’s likely you’ve smelt their wretched stench up close and looked into their feverish eyes as they screamed, pushed, shoved, punched and kicked at you in a mob consisting mostly of bad hair, hate-filled self-righteousness and placards.

They are the group that shuts down meetings with which they disagree using violence and the implied threat of violence. They are the group that is allowed to do so by Victoria Police, and increasingly other police forces across Australia as well. They are the group that decides whether or not you are allowed to speak in our country or whether you will have to pay $50,000 for the privilege.

They and their allies de-facto control the public square of our society and make certain that the political conversation drifts ever further to the left by intimidating and ultimately culling any voices on the right that dare step out of line.

They are the reason that universities are not simply left-leaning, but so far to the left of mainstream Australian society that I doubt you could find a single humanities student or staff member who would openly support the current date of Australia Day, despite that being the position of 70% of the wider population.

They want to destroy everything in our society. They hate our country; they hate the people who founded it and the culture they created. They hate our constitution, our history and our flag. They hate the police, the armed forces and the memory of the Anzacs.

And if you are of the demographic that typically reads this website, they hate you. They can’t wait for you and everyone like you to die off or be swamped by imports so that they can take control of the society you and your ancestors built and demolish it.

They are Socialist Alternative, the biggest, best organised, most fanatical and most violent political extremist group in Australia today.

So where did this group of extremist lunatics come from?

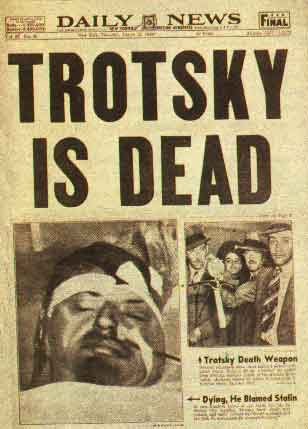

From the day of the Ice Pick to the fall of The Wall

To find out the origins of the group we have to go back a fair way.

The first thing to understand about Socialist Alternative is that they are Trotskyists.

The left-wing British writer Nick Cohen correctly described the followers of Trotsky as the loneliest force on the 20th century far left. After Trotsky lost his factional fight with Stalin and was forced into exile, his supporters were a tiny group of strange oddballs, even by extreme left standards. After old Leon met his doom in Mexico City by way of an ice-pick wielded by a Stalinist assassin, most people expected them to fade away altogether.

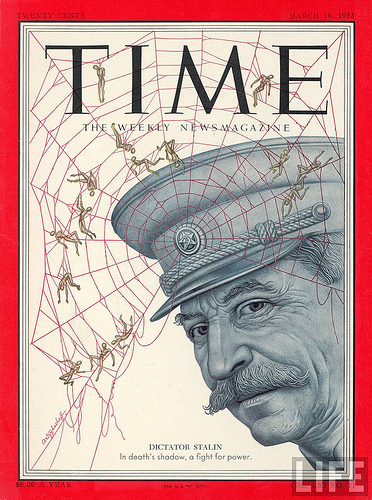

Most Communist parties throughout the world had already expelled Trotskyists from their ranks by the time of his death. They were alone, shivering in the cold. Most of the world’s left-wing intelligentsia considered Stalin’s Soviet Union to be the way of the future, and most outside leftish circles found the Trotskyists’ insistence that if only Leon had been in charge of the secret police then everything would have worked out perfectly to be unconvincing.

Cut off from relevance and persecuted by their mainstream Communist brethren, the Trots contented themselves with building small, ever more fanatical parties, participating in power plays for control over said parties, and of course splitting the parties into even smaller parties whenever there was the most minor disagreement.

One of these tiny splits in Britain was prompted by a disagreement between notorious rapist and megalomaniac Gerry Healy and the boringly ascetic yet no less of a megalomaniac Tony Cliff (birth name Yigael Gluckstein).

The doctrinal differences were small: Cliff believed that the Soviet Union and the new Stalinist Communist states of Eastern Europe should be described as “state capitalist” regimes; Healy on the contrary believed they should be called ”degenerated workers’ states”.

Clearly with such an inseparable divide they could no longer continue as part of the same group, and Healy expelled Cliff and all eight of his followers in 1950. After twelve years of hard effort, mostly recruiting inside the British Labour party, by 1962 Cliff’s fanatically devout congregation had grown to two hundred, and after a reorganisation christened themselves the “International Socialists”.

Internationally they began to spread the Cliff interpretation of “correct” Marxism as part of a network known as the “International Socialist Tendency” which at its height had branches all over the world.

So what does this have to do with Australia?

Well, during the Vietnam War protests in Australia, a whole bunch of small radical groups sprang up. While the war was never as controversial or unpopular in Australia as it was in the U.S., the universities apparently bristled with students who wanted to get themselves some free love, free weed and wave around Viet Cong flags to trigger the squares.

Stalinism had lost a bit of its lustre after Khrushchev’s Secret Speech, the 1956 Hungarian uprising and the 1968 Prague Spring, so most of those young university students being drawn to Marxist ideas for the first time went for the friendlier, nicer, not-at-all-genocidal Maoist version or stayed relatively independent.

One of those new more independent groups was formed in December 1971 in Melbourne (where else?) as the “Marxist Workers Group” by activists Dave Nadel and Chris Gaffney. It was broadly aligned with Trotskyism but mostly because the only other real option in Melbourne at the time was the Maoist “Worker-Student Alliance” set up by the pro-Chinese breakaway section of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA-ML).

That relative independence changed when three immigrants already associated with the British led International Socialist Tendency arrived. Tom O’Lincoln and Janey Stone came from the United States and Ross McKenzie from Britain itself; they joined up immediately and began spreading the gospel of St Tony Cliff. At this stage the group was fairly loose and even contained some Anarchists. As internal struggles for dominance raged the name of the group was changed first to “Socialist Workers Action Group” and then after the followers of Cliff had achieved the ascendancy to “International Socialists”.

It was the time of Whitlam and the left was on the march. Monash University in Melbourne became a fierce battleground as Trotskyists and Maoists struggled for the ascendancy. Eventually the former out-recruited the latter, in no small part due to the fact that the Maoists actually had to defend Maoist China, whereas the Trotskyists then as today were free to build ideological castles in the air.

That’s more or less the origin to the “Real Socialism has never been tried” meme. Because Trotsky never had the chance to fail, his followers down to this day never have to base their claims on anything more substantive than the dreams of decades of deluded utopian fanatics.

The mid-seventies saw the I.S. spread to Sydney, where they recruited former Communist Party of Australia member Graeme Grassie who then started a Brisbane branch. Two further British I.S. members migrated to Australia and set up an Adelaide branch in 1977. Smaller Marxist groups in Hobart and Canberra joined as well. Despite all this impressive activity, the national membership still didn’t top more than seventy in 1977. Each new recruit was an effort, each new branch a reach.

In the early 1980s the pro-life group “Right to Life” became a favourite target for the I.S. Despite their small numbers they found that the Christian families protesting for the rights of the unborn were easy to intimidate with a minimum of bullying violence and a maximum of yelling. The younger activists attracted by these new events began to fetishise the violent stomping of defenceless opponents into the ground. This was a sign of the evolution the group was undertaking that would influence its activists well into the future.

The I.S. had failed miserably in its attempts to get inside the union movement. Workers didn’t want to listen to them and the students they sent into the factories and trades to “industrialise” them resented being ordered out of a nice comfy university classroom and were resented by their workmates in turn.

In wider Australia, Bob Hawke had won the Prime Ministership and had done deals with the unions that seriously reduced the incentive to strike. The days of always having a strike to sell their paper at were gone, and along with them any delusion that their group was anything but a small bunch of university students and middle-class paper-pushers with no real power.

The I.S. retreated into itself, developing the “propaganda group” idea where every recruit is indoctrinated to a far greater extent than before. They had always fought against other far-left groups but now the hostility came to a new level.

Some members, amongst them the American import Tom O’Lincoln, split from the main group for a few years as internal faction fights and arguments over smaller and smaller points of doctrine or tactics attempted to distract their members from the fact that outside their meeting halls the world was turning away from Marxism. Both the original I.S. and the splinter group intensified their activism and asked more and more of each one of their members. Forcing them to pursue the sunken cost of so many hours of activism, so much time wasted in absurd meetings bickering with each other, that the stakes, at least in their own minds, became ever higher, ever more severe.

In the wider world of the ’80s, Hawke in Australia, Thatcher in Britain and Reagan in America had begun to shift the window of argument away from governments nationalising the commanding heights of the economy. Union power was dwindling, and when your entire ideology predicts that Unions will eventually conquer the state, that can be a little dispiriting. The orders and dictates that continued to flow through from the parent group in the U.K. began to have less and less relation to the reality on the ground in Melbourne and Sydney.

Eventually, against the wishes of the British hierarchy, in 1989 the splitters re-joined, the holes were patched over and a new start begun with a new name: the International Socialist Organisation.

Then the Berlin Wall came down. The Soviet Union dissolved, and in the eyes of the wider public, Communism as a system was entirely discredited.

Much like those cultists who wait all night for the end of the world then double down twice as hard when it doesn’t come, the ISO and other Trotskyist groups took the end of the USSR as a validation that they were right all along. The long struggle against Stalin that had begun before any of them had been born was finally over! Trotsky had been right!

If the rest of society disagreed well that was just their bad luck.

For the ISO at least there was a bit of genuine cause for celebration. The turn away from union work and towards student activism that they had decided to undertake after reuniting with their splitting comrades paid fruit with the coming of the Gulf War. A number of left-wing students were apparently hungry for activism, and as one of the few far-leftist groups left standing, the ISO was in a position to pick up quite a few recruits, increasing their numbers from 150 to 250 in under a year.

But as the ’90s began, trouble was on the horizon.

1995: The birth of Socialist Alternative

The ISO entered the post-Soviet era full of uncertainty and without clear direction. They were still the second-largest extreme left-wing group in Australia, and as the old Stalinist and Maoist holdouts began to fall away or dissolve themselves into the ALP and the Greens, it appeared that the organisation had reached a crossroads.

In the U.K., the ISOs parent group had been shell-shocked by John Major’s 1992 election victory. They had been certain that after the decade of Thatcherism, an ongoing recession, a war in Iraq and rising unemployment, that the country would be ripe not only for the British Labour Party but for outright unadulterated Communism. When Major and the Conservatives not only won but received the largest number of votes in a general election in British history it sent the wider British left into a spiral of depression and despair.

Grasping for hope, the now elderly Tony Cliff sent out the word that all was not lost, and that the world was now entering a period he described as the “1930s in Slow Motion” where Capitalism would falter again just as it did during the Great Depression. The message was sent out both to the Australian party and to all other member organisations of the IST that this perspective was now official holy writ and that all comrades should change their strategies accordingly.

According to Cliff, a great uprising of the worldwide working class was imminent and all Trotskyist groups needed to prepare themselves accordingly. The 1990s were apparently going to be the decade that finally saw the death of Capitalism and the triumph of “true” Trotskyist Socialism.

It’s fair to say that some members of the ISO found this new strategic approach (where a group of only about 250 people was being asked to begin preparations to take over Australia) to be slightly over-optimistic.

Two members of the leadership, Sandra Bloodworth and Mick Armstrong, began to speak up against the new approach, and as a result they were demoted in 1993. They continued pushing against the new strategy outside the leadership with the support of activists such as Jeff Sparrow, his sister Jill Sparrow and Tony Hartin. In July 1995, in an initiative led by Ian Rintoul and backed by the ISO National Committee, all five were expelled.

This caused uproar amongst the wider ISO membership. Those expelled had been given no chance to appeal or even defend themselves. Armstrong and Bloodworth had been activists in the group for decades and the Sparrow siblings were heroes to the younger rank and file due to their exploits during the Austudy Five controversy.

In less than a week, another eleven members were expelled, this time by telephone. Included in this round were university campus activists Jerome Small, Linda Memery, Asok Rao and Fleur Taylor. These members were directed to make loyalty oaths or face expulsion. They refused. A meeting in Sydney on the 2nd of August, attended by 25 current and former members, condemned the Melbourne purge, and many indicated their intention of resigning from the ISO.

The expelled members in Melbourne met on the 10th of August 1995 to discuss setting up a rival organisation. Including those from outside Victoria who had defected, those willing to start a new group numbered around fifty, mostly confined to the Melbourne metropolitan area. They were predominantly young, full of outrage and firmly behind the new leadership of Bloodworth, Armstrong and the Sparrows.

And Socialist Alternative was born.

It’s worth thinking about what would have happened if that split had not occurred in 1995. The ISO and the other Marxist groups in Australia would have likely continued on the trajectories that have seen them decline to this day. To be sure, if the activists who left had stayed on board the ISO, it might have helped that organisation limp on a little longer (it finally voted to dissolve itself in 2008) but it’s possible that extreme left politics would be far weaker today in this country than is otherwise the case.

A large part of this is due to Mick Armstrong. Armstrong joined the ISO as a student at La Trobe University in 1974. He worked his way up the ranks and was a part of the group of Melbourne activists who moved to Sydney to “colonise” it with a new branch. In the early 1980s he was a leader of an internal group advocating for more violence against political opponents (particularly Christians), arguing that once the extreme left had enough boots in the street, “military” considerations were all that mattered. At one point he was sent by the national leadership to Brisbane to take control of the Branch there. He was unpopular in the Sunshine state and was quickly replaced, but not before coming into conflict with one Ian Rintoul (then a rising young hard-line activist from Ipswich) for the first time.

He was, in short, an ISO man to the core. Fanatical, violent, disciplined and committed.

Armstrong had watched with mounting concern as the ISO had begun to follow the orders from Britain and had changed almost everything which he considered to have been successful in the past. Now that he had been expelled, he decided to base his new group on the three principles that he believed had stopped the ISO from growing and had led it towards irrelevance:

- That the most important task was to individually brainwash every new recruit into the “correct” form of Marxism as thoroughly as possible. That a smaller group of hard-core activists is less likely to be affected by outside trends in society and so is more likely to keep the “true” Marxist faith than a larger group with less focus.

- That trying to pretend that you are a huge mass Communist party with strong base in the union movement is ridiculous when you aren’t, and that doing so leads to tactical and strategic mistakes. That the most important thing for a small group to do is to realise that it is a small group and act accordingly.

- That a group needs to recognise where its best recruits are coming from and orient themselves and whatever resources they have in that direction. In Socialist Alternative’s case, this was the university campuses.

Looking back twenty years later, it’s clear that Armstrong was correct. His main rivals and the then largest leftist extremist group the DSP (Democratic Socialist Party) along with the ISO founded the Socialist Alliance in 2001 in the belief that Australian workers really were ready to vote for a big dose of unreconstructed Communism. They were wrong, and the decision to pour all their resources into elections ended up killing the ISO (even Ian Rintoul jumped ship in 2003) and crippling what was left of the DSP, which eventually folded itself into the Alliance in 2010.

Meanwhile Socialist Alternative now stands almost uncontested as the largest, best organised and most violent political extremist organisation in Australia.

How did that happen?

You can read part 2 here.