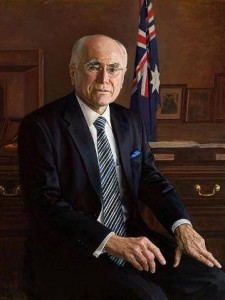

Among the portraits of Prime Minister’s past hanging in Canberra’s parliament house, that of John Winston Howard, Australia’s second longest serving Prime Minister, is the only one to feature an Australian flag. The presence of the national flag in the context of his portrait speaks volumes about the man, his values, and his legacy.

John Winston Howard was born in 1939, in a very average Sydney suburb. After training and working as solicitor for several years, he was first elected to parliament in the safe Liberal seat of Bennelong in 1974, and served the constituency continuously until famously losing the seat, and government, in the 2007 election. John Howard was Australia’s treasurer during the government led by Malcolm Fraser from 1977 to 1983, and was then an unsuccessful leader of the opposition, losing the 1987 election to Labour’s Bob Hawke. For many, lesser men, that loss might well have been career ending. But not for John Winston Howard. After several years in the political wilderness, he was again entrusted with the leadership of his party in 1995, and led the Liberal-National party to victory in the 1997 election, defeating one of the greatest narcissists in Australian politics, Paul Keating.

Last year this correspondent heard the aforementioned Paul Keating give a speech at a black tie dinner raising funds for a public building and institution. In addition to reminding the room, containing many of the city’s most influential and powerful people, that his was undoubtedly the largest intellect present, Keating went on to give a speech premised entirely on the notion that every achievement of an Australian government in the last few decades of any lasting merit, was made during the years of his Prime Minister-ship, whilst his successor (John Howard), it seemed clear in the world according to Paul Keating, had contributed absolutely nothing of any substance to public life whatsoever. At one point, with his face shining in the spotlight of a photographer’s flash, it seemed highly likely an angelic choir would appear singing the Hallelujah chorus mid speech. The contrast with John Howard could not have been greater. In public, Howard is gracious to past opponents on both sides of the political fence, and willing to give credit to others for their achievements. Whereas Keating exhibits the typically embittered and egotistical and self-entitled persona of the political left, Howard is gracious, humble, and impeccably decent.

Last year this correspondent heard the aforementioned Paul Keating give a speech at a black tie dinner raising funds for a public building and institution. In addition to reminding the room, containing many of the city’s most influential and powerful people, that his was undoubtedly the largest intellect present, Keating went on to give a speech premised entirely on the notion that every achievement of an Australian government in the last few decades of any lasting merit, was made during the years of his Prime Minister-ship, whilst his successor (John Howard), it seemed clear in the world according to Paul Keating, had contributed absolutely nothing of any substance to public life whatsoever. At one point, with his face shining in the spotlight of a photographer’s flash, it seemed highly likely an angelic choir would appear singing the Hallelujah chorus mid speech. The contrast with John Howard could not have been greater. In public, Howard is gracious to past opponents on both sides of the political fence, and willing to give credit to others for their achievements. Whereas Keating exhibits the typically embittered and egotistical and self-entitled persona of the political left, Howard is gracious, humble, and impeccably decent.

The contrast between Howard and Keating has also been played out politically on the national political stage, and is a matter of the historical record. Keating won a single election, and was then voted out at the next one in a landslide. Howard won four elections, including the 1998 ‘GST election’ in which he triumphed with a policy platform that would have been electoral poison and meant certain political death in other hands, including as it did, the introduction of a new broad based consumption tax.

John Howard achieved a great deal during the course of his years as Prime Minister – actual economic reform, gun control legislation that has become the envy of the world, and a successful asylum seeker regime that left only four people in detention at the time he left office. The mark of the success, and rightness, of the policies implemented and pursued by the Howard government are clearly evident in the manner in which they, and he as their architect, are so often recalled. ‘The Howard government got this right’ is a sentence heard many times, especially in the context of the asylum seeker debate, and in light of the public policy disaster inflicted on the nation by the catastrophic Rudd-Gillard-Rudd government.

But it is not so much his policies, as significant and successful as they were, that are the continuing legacy of John Howard and ‘the Howard years.’ As the portrait, with the Australian flag in the background, symbolises, John Howard steadfastly refused to indulge in the politically correct game of attributing blame for current social ills to the past. His instinct was never to see and think the worse of those who had gone before him, nor of his fellow Australians. As he put it himself, he refused and repudiated the ‘black armband view of Australian history.’ Australians have never been given to emotive and public displays of patriotism. John Howard made it acceptable and, further, gave a sense of rightness to being proud of, and grateful for, the enormous achievements of Australia since white settlement, contrary to the cultural elitists, who wanted only to talk about the very worst expressions of white Australian history. With John Howard at the helm, Australians felt good about themselves, about their history, about the principles of free speech and the rule of law inherited from Britain, and about their flag and all it represents and continues to represent.

The particular genius of John Howard as a political leader was the manner in which he was able to sustain a narrative of aspiration and hope, whilst taking the people with him, including, famously, ‘Howard’s battlers,’ the largely middle or working class suburban folks looked down upon with derision by inner city leftists and elitists, who felt abandoned (with good reason) by the so-called ‘workers party’ (Labor), now captive to careerist unionists. John Howard was the quintessential ‘everyman,’ embodying the values and principles of the largely silent majority of decent, hard working, law abiding people. John Howard is, and always will be a genuine Australian hero.