John Elsegood

If old cowboys never die but merely ride into the sunset then Wynand Du Toit epitomises the fact that old soldiers being hard to kill simply write into the sunset.

Du Toit joins another famous POW, South Vietnam’s Colonel Vo Dai Ton, to turn wordsmith and both had their freedoms curtailed fighting communists during the Cold War.

South Africans were engaged in the Cold War in Angola, on a limited scale, from 1975, to prevent further problems in the SWA (Namibia) a territory then controlled by the RSA . The South Africans had no wish to see SWA insurgents gain help from a Marxist Angolan state receiving USSR and Cuban help. If SWA also became inflamed by communist insurrections and foreign troop penetration then incursions across the Orange River would duly follow into South Africa.

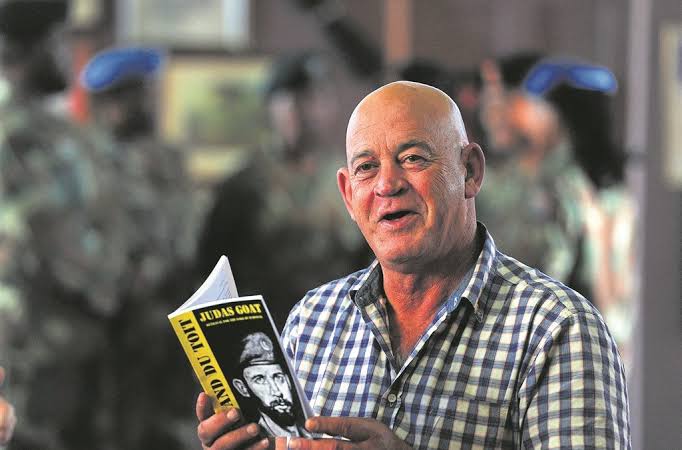

Apart from defending the RSA against the Cubans and Marxist MPLA forces in the Border War in Angola, Du Toit quipped during a Perth visit, promoting his books, that he usually only used English in self defence which was fine because some of his audience that were rooineks, could only laugh in Afrikaans! Fortunately the former elite SADF soldier caters for his uitlander reading public with English editions available.

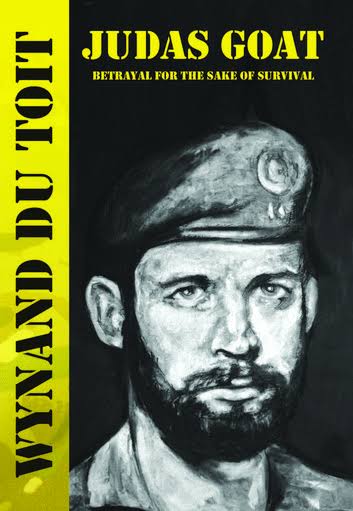

In his first book Judas Goat, Du Toit considers the mission was betrayed from within, hence the title.

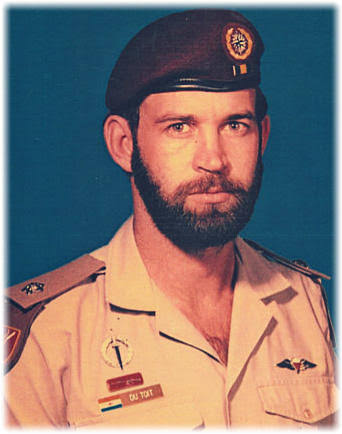

In May 1985 a Special Forces team consisting of nine operators landed on a beach in the oil rich province of Cabinda, (Operation Argon) in Angola. Their target was to blow up six massive oil storage tanks. In the fire fight two SADF soldiers were killed and Captain du Toit captured. Indeed he was lucky to survive, after being wounded he was deliberately shot in the neck by a FAPLA (Angolan Marxist) soldier.

“It should have been easy, get in, blow them up and get out by submarine, instead I spent over 800 days in captivity.”

Told by his captors “your government told us you were coming,” Du Toit told the Russian officer ‘where to go’ in two short words. “But it made me think,” he said.

Du Toit knew the operation was a department of Foreign Affairs project, rather than Defence.

What concerned him was the fact that he was landed 21km from the installation and the fact that he was told specifically where to take cover by the chief of the SADF General, Constand Viljoen, and was threatened with removal as leader if he did not follow those instructions.

Instead of having current photos of the oil installations he had none and found out years later the photos had been removed prior to the operation.

He details some notorious press conferences that were divided between East and West. Not surprisingly, the Soviet bloc hacks focused on South African ‘aggression’ towards neighbouring states to which the captured SADF captain invariably replied, correctly, that South Africans were the victims of Soviet aggression.

It was the small SADF presence in Angola that prevented the Marxists of SWAPO, from marching to the SWA capital Windhoek and on to, and across, the Orange River into NW South Africa.

That didn’t stop American politician Rev. Jesse Jackson, from a disgraceful attack on the prisoner, who was a US ally in the Cold War, no matter how much Jackson may have disliked that fact. In fact it was the Cubans who were the invaders on African soil unlike the South Africans who were engaged in forward defence to safeguard their soil.

Yet for two hours Jackson and his press poodles berated du Toit with political questions about how racist and fascist the South Africans were, despite the fact the Afro-American minister once derisively referred to Jews as ‘Hymies.’

Jackson’s disapproval of US-South African ties was frankly irrelevant. Both the Reagan and Botha administrations were allies in the Cold War involvement against the Marxist regime in Angola and its communist allies, Cuba and the USSR. Therefore, Jackson betrayed his own country and denied another human the dignity he should have been afforded by a fellow Christian, particularly one calling himself a Man of God.

Jackson simply demeaned himself, while du Toit’s conduct was impeccable. Indeed, he was reminiscent of Colonel Vo who, after being coached in what to say by his captors, was paraded before the media, in 1982, by the communist Vietnam regime but simply refused to denigrate the US or its allies.

Vo was beaten for his performance but du Toit, while naturally upset at Jackson’s abuse, was later cheered up by a Cuban colonel who said, “who the hell is Jesse Jackson anyway?” As the then SADF captain noted: “It made my day.”

Indeed, both men show how lonely being a political prisoner can be and writing became an escape from deprivation.

The recent death of RF (Pik) Botha (12 October), at one stage the longest serving foreign minister in the world, when the National Government fell in 1994, would not have seen the former SADF officer shed a tear.

DuToit makes it clear, by insinuation, in many places in his book, he has little love for the former foreign minister and his feelings of betrayal, from the top, is sheeted home to Botha.

Bitterness, loneliness, worry are clearly evident in men like du Toit, Vo and, perhaps the great prisoner-writer of all, Albert Speer, Hitler’s Armaments Minister, who spent 20 years in Spandau Prison after WW2.

However, Wynand du Toit and the serving men of the SADF have nothing to reproach themselves over.

They simply deserve, and have, respect for holding the line in the Cold War.

Despite the jaundiced opinion from western liberals and Marxists the SADF neither started the war in Angola and neither, as some alleged, were they defeated at Cuito Cuanavale. But in a sense du Toit’s feelings of abandonment is a microcosm, or mirror image, of the treatment that his nation received in the long conflict.

From small beginnings as an essentially police operation in August 1966 the conflict escalated over the following 23 years to include the SADF three factional Angolan forces and the USSR and Cuba with some 55,000 soldiers of the latter involved, at the end.

Some four US administrations were also engaged – Ford,Carter, Reagan and Bush Snr, with the South Africans being their proxy in the long running Cold War engagement.

The fall of the Portuguese regime in April 1974 led to the new left wing military regime in Lisbon to pull out from its African colonies –Angola and Mozambique immediately.

Both saw Marxist regimes take over and in Angola the MPLA had no intention of adhering to the Alvor Agreement to reach a constitutional power sharing with the FNLA and UNITA. The result of that classic piece of Marxism was a messy civil war.

Contrary to the manic and maniac claims of the communists and their fellow travellers in the West the South Africans did not predate the Cuban presence in Angola. Academic researcher Piero Gleijeses claimed Fidel Castro’s decision to use force was on 5 November 1975 some two weeks after the South Africans crossed the border. However, he says nothing about the decision by the USSR, to ensure that their friends the MPLA should be the only power in Angola. Hence, from December 1974 there was a flow of arms, instructors and advisors to the MPLA, accelerated in March 1975, a fact that was duly noted by the SADF.

With skirmishes at the Calueque hydroelectric dam in Angola, which supplied electricity to SWA, the South African Government sent in 1000 of their troops into Angola to protect that site.

In early October the Cubans sent in 1000 troops and equipment- still before any appreciable SADF response.

The Cubans intervened on one side in a three cornered dispute and was never there at the invitation of an established Angolan government but rather as a blatantly opportunistic act because the US had been weakened by the Watergate trauma and resignation of President Richard Nixon, in August 1974.

The subsequent failure of a craven Democratic Congress, plus the Ford and Carter administrations, to deal with the problem led to a protracted struggle because South Africa, rightly, was not prepared for external communist interlopers to threaten its territory (SWA) with the concomitant potential to then mount incursions into the RSA in the Northern Cape region.

The Border War eventually finished with a diplomatic solution, signed at the end of 1988, although even then SWAPO guerillas ‘pushed the envelope,’ in the first nine days of April 1989, by invading SWA, from Angola, before being comprehensively dealt with by South African police and security forces for their blatant breach of the peace process.

For once, PW Botha’s Government received international support for dealing with the cross border outlaws, an appreciation hitherto lacking by the West.

If du Toit is correct in describing himself as a pawn in an international chess game then perhaps too the grandiose plans for southern Africa of Fidel Castro also fell victim to the ‘cocktail set,’ due to an unlikely duo –Pretoria’s man in Washington, ambassador Donald Sole, and Reagan’s National Security Advisor, William Clark.

Clark and Assistant secretary of state for African Affairs, Chester Crocker, accepted the linkage proposal that Sole was propounding. The veteran South African diplomat made it clear that South Africa would not withdraw from Namibia while so many Cuban troops were just over the northern border in Angola. Indeed, if SWAPO and Cubans ever marched into Windhoek the South Africans would come straight back over the southern Orange River border and it would not be the limited response, as in Angola.

The Nine Day War had been a small portent of things to come for the Marxists if they had wanted to further escalate conflict in SWA.

Despite all the boasting of Castro about spurious Cuban ‘victories,’ he had, in fact, been thrown a lifeline by the New York Accords, of 22 December 1988, which led subsequently to all-race elections in Angola, Namibia and South Africa; while men like du Toit paid a heavier price for defending freedom against totalitarian thugs, masquerading as liberators.

John Elsegood writes at Something Else.