Ever wonder why it doesn’t seem to matter who’s in power, things always keep moving in the same direction?

Ever stop to ask yourself why, after the supposedly “social conservative” John Howard had been in office for eleven years, the country was still further to the Left than when he started?

Ever wonder how gay-marriage went from an absurd joke that even gay-activists laughed at in the 90s, to a moral litmus test for polite society today, to probably a staunchly defended “conservative” position in ten years’ time?

The answer is simple. Elected politicians rarely if ever actually change anything themselves; they only use the power of the state to enforce changes that have already happened in the culture.

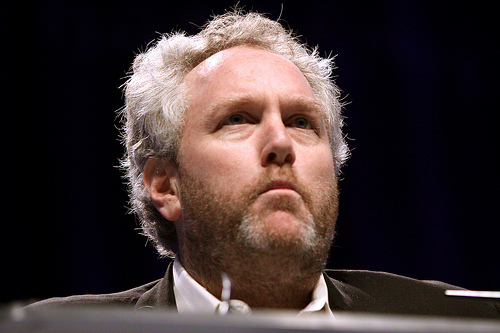

It’s been said in one form or another by everyone from the late Right wing bomb thrower Andrew Breitbart to French philosopher Alain De Benoist to the Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci. Politics is downstream of culture. It is difficult if not impossible to institute a lasting political change unless support in some form exists in the culture of the community itself.

The total inability of almost any faction at all on the Right to realise this and do something about it is why we keep losing the Culture War and suffering the political consequences that go with it.

Gramsci probably articulated it best. Writing from prison (into which Mussolini had rightfully thrown him for being a dirty Communist) Gramsci used his theory of “Cultural hegemony” to try and explain why stupid working class people kept persistently refusing to follow where enlightened Marxist philosophers (such as himself) were trying to lead them.

Gramsci argued cultural wins precede political wins. He understood that Marxists were failing to overthrow the bourgeoisie because they hadn’t gained control of the culture. The support of the people must be gained first, Gramsci argued, and the best way to achieve that is to slowly change their ideas, values, culture, and worldview.

You do this through societies’ institutions, of which political parties are only one small part. Normal people don’t have the time or the inclination to think through every idea floating around so mostly we take our cues of what is normal and acceptable from the institutions we trust in our society.

Gramsci though the best way to change the ordinary people’s worldview (full of stupid irrelevant things like God, nation, family and tradition) was to build new parallel “proletarian” institutions which would indoctrinate people in a properly “proletarian” culture. Only then, in his view, could the glorious Communist revolution proceed.

In the years following the Great Depression, Communists around the world generally did try this, working from within the union movement when they could and outside it when they couldn’t. They had some success and kept their ideologies alive in the Western world, but in most countries, it was not enough to change their ideas from being “Slightly Weird” to “Normal” for the majority of the public.

The problem was ordinary people still had too many other institutions influencing them. Churches, community organisations, schools and especially the family all had far more influence on people’s moral development, values and worldview than a few professors ranting about long dead bearded economists or the one bloke in the workshop constantly preaching revolution.

Then came the generation of 1968. Less orthodox Marxist thinkers such as French philosopher Louis Althusser and German student leader Rudi Dutschke argued that a better strategy than trying to build parallel institutions was to by simply take over the ones that already existed (and which ordinary people already trusted) through infiltration.

Dutschke even coined a term to describe this process, “The Long March through the Institutions”, taking his inspiration for the name from the march carried out in China by the mass murdering dictator Mao Tse Tung.

This strategy was taken up eagerly by the university radicals of the early baby boom. The appeal is easy to see; not only did they get to be “radical revolutionaries” but they also got to work in nice jobs and enjoy a comfortable middle class existence. What’s not to like?

Most of those who were inspired by this idea and chose this path eventually moved the economic ideas of Marxism into the background while replacing the evil bogeyman of the oppressive “bourgeoisie” with the even more evil bogeyman of the oppressive “White male” to create what we today call Cultural Marxism.

Slowly but steadily they spread from the Universities through to the educational system, the arts, the public service, the media, the NGOs, the philanthropic networks and other charities, and eventually went so far as to influence the boards of sporting organisations as well as the hierarchies of the police, intelligence services and the military.

Eventually even the Churches, once the great cultural opponents of the extreme Left, began to fall in line.

Most of those “Marching” were not by this stage Marxists themselves but had been educated and immersed in an environment where a neo-Marxist and later Cultural-Marxist worldview was acceptable or even dominant.

The process took many decades, but eventually what had begun as a strange idea by beardy hippie types in Europe led to our modern world, where the commanding heights of our society’s institutions are on the verge of making it immoral to disagree with the idea of five year olds undergoing “gender reassignment”.

But the situation is not hopeless. The experience of Trump, Brexit and the ongoing populist revival in Europe shows what can happen when the Left tries to move politics faster than they’ve already moved the culture. Most Leftists are now so secluded in their bubbles that they genuinely thought they’d moved the window of opinion further than they already had. This led them to overreach which then almost inevitably sparked a backlash.

But that electoral backlash means nothing without cultural change. Most of the West exists in some form of two party system. Even in the more multipolar European political structure the pendulum does swing back and forth.

The Left will win power again and when they do they will continue to use the apparatus of the state to enforce the cultural changes they have made and are continuing to make right now via the media, the education system and all the other institutions they have captured over the last 60 years.

The solution is not to start yet another minor political party on the Right (I think we already have about six) but to begin a march of our own.

Most of the times I suggest this I hear Right-wingers whinge: “But we don’t have enough time! It’s impossible! The Left has too much of a stranglehold! Something something blah blah demographics! Only by founding yet another tiny micro party can we save Australia!”

It amuses me because these arguments are so similar to the more orthodox Marxist attacks on the “Long March” strategy back in the late 60s when it was first suggested. In the eyes of the old reds the revolution was always just around the corner, and these bearded no-good young’uns were distracting energy that could be better used preparing for the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The only real way to make long term, permanent changes to society is to change the culture. To do this you can either change the people (as though immigration) or change the institutions the people trust. Coups, revolutions, riots and elections all fail as mechanisms for change unless the culture has already changed first.

The moment the Australian Right wakes up to this fact, the moment the Right stops thinking that all we have to do to win is drop a piece of paper in a box every few years, the moment we stop arguing about conspiracies on the internet and get off our arses to organise one of our own, is the moment the long road to positive societal change can begin.

Photo by Abode of Chaos