Chips O’Toole

It is somewhat serendipitous that the AFL has chosen this coming weekend for its latest act of political folly, the inaugural Pride Game.

With the match set to fall right in the middle of the Rio Olympic Games, it’s a scenario that provides a perfect juxtaposition between two vastly different approaches to the vexed issue of politics in sport.

In the case of the AFL, we have a sporting organisation embracing an ever-growing agenda of social engineering; in the case of the International Olympic Committee, a governing body that has fought doggedly to keep politics from the field of play.

Of course, it would be foolish to suggest the Olympics are completely free of politics. Indeed, the Games may well be the most politicised sporting event in the world. Even if we accept the Olympic ideals of egalitarianism, pacifism and nationalism as part of the broad terms of reference for all international sport, we are still left with a legacy that includes the Nazi Games of 1936, multiple boycotts by various countries, the ban on South Africa through the apartheid era and, most recently, the Russian doping scandal.

Still, for its part, the IOC has been largely successful in ensuring the focus inside Olympic venues remains firmly on the sporting action. This has been achieved through the implementation of Rule 50.3, which states that “no kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.”

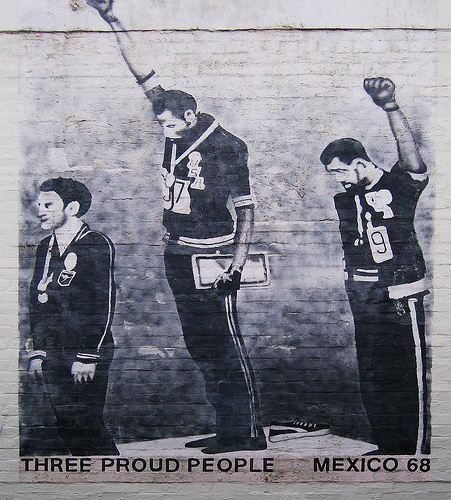

As exemplified by the infamous Black Power salute at the 1968 Mexico City Games, this stance has not always endeared the IOC to the wider public. While the gesture received a savage reaction at the time, popular opinion has shifted dramatically over the years. Today, the salute is widely regarded as one of the most iconic sporting images of the 20th century, with the three men involved – Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who performed the salute, and Australia’s Peter Norman, who stood in solidarity with his rivals by wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge – praised as civil rights heroes and the officials responsible for banning Smith and Carlos from the Olympic Village as villains.

As exemplified by the infamous Black Power salute at the 1968 Mexico City Games, this stance has not always endeared the IOC to the wider public. While the gesture received a savage reaction at the time, popular opinion has shifted dramatically over the years. Today, the salute is widely regarded as one of the most iconic sporting images of the 20th century, with the three men involved – Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who performed the salute, and Australia’s Peter Norman, who stood in solidarity with his rivals by wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge – praised as civil rights heroes and the officials responsible for banning Smith and Carlos from the Olympic Village as villains.

However, such views miss the point, seeming to paint the disciplinary action of the IOC as a specific statement against civil rights rather than a matter of principle.

It’s entirely possible officials were riled by the symbolism of the gesture. Contemporary views of the US civil rights movement tend to focus on the broadly positive outcomes of the end to racial segregation and discrimination and the peaceful protests advocated by leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr, ignoring the militant black nationalistic elements that often resorted to violence and undermined white support for the cause. Smith himself has even gone to some length to paint his actions as a “human rights salute” rather than a Black Power salute to distance himself from the controversial Black Panther Party, which used a strikingly similar gesture.

That, however, is neither here nor there. Whatever Smith and Carlos’ intent, and however their cause sat with the upholders of the IOC law, failure to hand down punishment would have been a betrayal of the IOC code. It would have sent the message that, rather than relying on a consistent approach, the IOC was content to use its own subjective judgement to determine which political causes were acceptable and which were not. More significantly, it would have removed any deterrent for other athletes, potentially opening the floodgates on similar protests that detracted from the sporting spectacle and threatened both harmony between competing nations and the overall viability of the Games. With the IOC having acted as it did in laying down the law, it is telling that few overt athlete protests have appeared in the 48 years since, despite a myriad of controversial issues surrounding host nations over that time.

It would be a stretch to suggest an organisation such as the IOC should feel compelled to let athletes usurp the Games for whatever political agenda they desire, but there is still something about the hard-line authoritarian approach of a blanket ban on all political statements that sits uncomfortably alongside the value we place on freedom of expression.

Perhaps, then, it’s worth considering the alternative as presented by the current state of the AFL. Far from even attempting to take any form of consistent approach to the use of its game as a political tool, the league has openly embraced and campaigned on whatever issue of the day it sees fit, in the process showing a stunning lack of self-awareness.

It has used the already-divisive concept of Indigenous Round to promote an equally divisive cause, the Recognise campaign, brushing aside the concerns of the many Australians who don’t want our nation’s legal framework to elevate people on grounds of race and Indigenous activist groups that believe constitutional recognition will undermine efforts to achieve real change for disadvantaged Indigenous Australians. It has refused to address the cynical brand of racial politics practised by Adam Goodes and his band of followers while implementing draconian sanctions on spectators who have dared challenged its agenda of unchecked multiculturalism. And now, after launching its inaugural Pride Game, it has collaborated with a complicit media to dismiss any criticism of the initiative as homophobia, apparently failing to recognise that concerns over issues such as gay marriage and the constant expansion of both the LGBTQI acronym and its accompanying causes do not amount to an outright hatred of gays.

Perhaps most concerning, it has done all of this while completely oblivious to the threat of alienating scores of fans who simply want to forget the heady issues of the wider world and sit down to enjoy a game of football without having a political agenda rammed down their throats, regardless of whether or not they agree with the sentiment.

For those fans, should the Pride Game prove a bridge too far, at least they can flick over to the Olympics for the night.

Chips O’Toole: Australia’s favourite son and a real dirty, rotten scoundrel.

Photo by Newtown grafitti