From Patriotic Alternative.

From Patriotic Alternative.

Matthew Lovecraft

“This is the final struggle

Let us gather together, and tomorrow

The Internationale

Will be the human race”

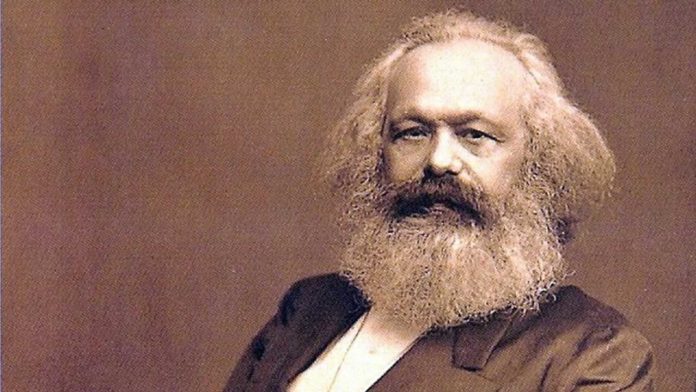

So goes the official anthem of the Communist Internationale, adopted by the Second Internationale – founded as an organisation of socialist and labour parties in 1889. While attracting anarchists and socialists of a variety of hues, the movement was heavily inspired by the writings and political platform of Karl Marx as the words of this anthem would more than suggest. For that reason it is often assumed that Marx was an internationalist in the sense that he believed that all peoples of the world would sooner or later embrace Communism with England and Germany, the most industrialised countries, leading the way through the proletariat revolution. It was commonly believed that Marx was referring to a movement forged to unite humanity, bringing social equality and justice by grasping the common ownership and control of the means of production. While Marx denounced utopianism, he appeared to predict, in works such as The Communist Manifesto (1848), that the entire human race would be liberated by Communism as an inevitable path to universal progress. Yet a deeper reading of Marx (especially those works written with his co-author Friedrich Engels) returns some statements in which he denigrates a number of races and with a tone that, in common parlance imposed by our current political and cultural elites and embraced by the Left-wing in general, would be regarded as ‘racist’.

The Jewish Question

Where Marx’s view of race is perhaps certainly strident is his much discussed work On The Jewish Question (1844). This publication constituted Marx’s first attempt to develop his materialist interpretation of history which underscored his anti-capitalist and revolutionary programme. He argued that political emancipation was insufficient for the liberation of man. What was needed, he maintained, was economic emancipation and a class consciousness freed from religion. The Jews, Marx insisted, were a fine example of how religion, in this instance Judaism, was intrinsically linked to economic life. Throughout his discussion there are strong indications, according to his critics, of anti-semitism expressed via Marx’s apparent stereotyping of Jews. For instance he says of the Jew:

“What is his worldly God? Money….Money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist. The bill of exchange is the real god of the Jew….The chimerical nationality of the Jew is the nationality of the merchant, of the man of money in general.”

While Marx’s On The Jewish Question is open to considerable interpretation, Hyam Maccoby, a British-Jewish writer, conjectures that this work indicated Marx was embarrassed by his own Jewish background and used the Jews as a “yardstick of evil”, reflecting discussions widespread across Europe, especially Germany, concerning the ‘problem’ of the Jews in diaspora.(1)

Race and Economic Development

Other attempts to trace Marx’s negative views of a number of races are few and far between. Perhaps the best analysis is presented in an academic journal article (on-line and well worth a read) by Erik van Ree. This author maintains that Marx’s theory of history contains strong racist references. He points out that in Marx’s (and Engels’s) view racial disparities surfaced under the impact of shared natural and social conditions, thereafter evolving into hereditary and blood lineage. In such an analysis, they played tribute to Darwin’s findings regarding natural evolution and connect this with social evolution. Thus Marx and Engels racialised skin colour groups, ethnicities, nations and even social classes, while endowing them with either superior or inferior characteristics. Races endowed with the former boosted economic development, while the lesser held humanity back. In conclusion, van Ree states that Marx and Engels view of a diverse range of races – Negroes, Slavs, Chinese, Bedouins, the Irish and others – as “horrendous”.

Marx and Engels remarks on race are scattered and unsystematic. But we can take a few indirect quotes by way of illustration:

– Engels insisted, in his Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), that the rich meat and milk diet of the Aryans and Semites accounted for the superior development of both races while, he claimed, the vegetarian Pueblo Indians had smaller brains than meat-eating Indians.

– Marx and Engels in their German Ideology (1846) suggested that the United States became the centre of the “most advanced social formations”‘ because of the energy brought about by ‘racial hybridisation’ of the English and the Germans and such hybridisation might indeed, be a way forward for the human race. The speculation seemingly comes close to a notion of racial breeding to spur on human evolution.

– Engels in Revolution and Counter Revolution (1851-52) characterised such nations as Slovenians, Poles and Czechs as “essentially an agricultural race” without proper appreciation for trade and industry and were some kind of developmental cul-de-sac, never to progress to higher economic forms typified by capitalism as a means of production.

– While using the ‘N’ word Engels, in a letter, described the typical black person as “a degree nearer to the animal kingdom than the rest of us, he is undoubtedly the most appropriate representative of that district”. For such reasons, Marx and Engels were able to justify slavery in the southern states of the USA.

Marx and Engels as ‘Racist’

Marxist scholars advance little or no discussion of Marx’s and Engels’s view of race in their literature. It remains a wholesale embarrassment, to be ignored like some badly behaved uncle. For those in the Dissident Right, Marx and Engels’s view of race is a gift in offering a critique of the Marxist Left irrespective of its various manifestations. Marx and Engels simply insisted through their writings that races differed in their abilities and hence civilisational potential. Or otherwise put, they regarded race as an element underlying the economic basis of society and possibilities of economic development or, indeed, a lack of it. It is worth pointing this out to our adversaries. If they respond by saying that Marx and Engels were after all a product of their own time and place and thus this explains their theory of race, the retort is: well then, was this similarly the case with their other theories, not least of all those of an economic and political nature related to the direction of human social evolution?*

(1) Hyam Maccoby (2006), Antisemitism and Modernity: Innovation and Continuity, Routledge.

* Since I wrote this article, and although not read the volume, I have become aware that the popular commentator and best selling author, Douglas Murray, deals the relevant writings of Marx and Engles in his recently published book The War on the West: How to Prevail in the Age of Unreason (HarperCollins publishers).