People often joke about how royal families are inbred, or wallow about wealthy people coming from wealth. Indeed, the truly self-made man is rare. But how does this come about? How does a noble bloodline form? What distinguishes them from everyone else? What does “good breeding” actually mean? This will be a very stuck-up, arrogant essay, so if that’s not to your liking then turn back now. The reasons these families form is itself very selfish though, so we have to adopt that mindset somewhat in order to understand it.

First, how do you begin an aristocracy? This is actually the simplest part. Get wealthy. That’s it, that’s pretty much all it takes to start. One ambitious, driven person making a few good moves, one after another, throughout their lifetime can ensure that their family is set up for the next thousand years. Generally, someone of means will be recognised by an authority – this could mean knighthood or some other commission. Sure, I grant this is a lot easier said than done, but relatively speaking this is easy. What’s hard is maintaining it.

There are hundreds of Rockefeller descendants. Due to the hard work of their patriarchs, virtually none of them live in want. They still hold immense power.

Alright, so how do you maintain an aristocracy? This happens when the wealthy, ambitious founder instructs their children in how to be responsible and virtuous in handling their inheritance. He then selects the most responsible child – generally the eldest – to hand the greater part of the fortune to. These children are not reared in the common sense. A good new aristocrat, probably emerging from the normal schooling of society at large, will not subject his children to the same conditions. Unlike him, his children are not expected to take a generalised route through life, but are instead expected to inherit and manage enormous tracts of wealth, business, and property. This is a specialised set of skills, and requires a unique education which is particular to their situation.

The bloodline is established after the first generation is successfully raised in this unconventional way. This is the point where someone is given their father’s name and becomes “the second”. However, it must be understood that the family name only lasts as long as this special rearing endures. How do you ensure that future generations are also given this understanding? Breeding.

We’re used to using this term about animals. We sometimes hear it in fancy Victorian dramas. The best way to make sure your descendants learn the same lessons you meant for them to learn is to marry them off to people who also had to learn those same things. You see, for the common folk it’s enough to marry over things like love, and values, and culture, and interests, and so on – I say this as common folk myself. But someone with a lot to lose doesn’t want to gamble it on someone who can’t possibly know how much work goes into building and keeping it. These people will form societies, hold dinners and dances, introduce their children to each other, and encourage keeping their blood wealthy. You can understand why marrying a commoner would be seen as shameful. It’s not just pride at stake, it’s the practicalities of having to somehow communicate the living sensation of wealth and privilege. It’s simply impossible to do for most people.

The old elite of America are concentrated in the maritime North East, the oldest parts of the country. They are generally polite, quiet people (for Americans, at least).

These lessons are indeed lost on most people. In a country like the USA, despite there being many thousands of millionaires, there are only a few families that ever hold onto their wealth after a generation. It’s precisely because of these illiberal lessons. In working class society, money is hard to come by, and it is saved under the mattress for a rainy day – or it’s blown as soon as it comes in. In bourgeoise society, the lessons taught about money are very different again, and it is usually either held in slowly appreciating assets or spent on lavish experiences and accoutrements, in general to look good in front of others. Where the aristocracies differ – and make no mistake, there are certainly aristocracies even in the liberal United States – is that wealth is handled very differently from these first two classes. For one, money is seen as something that can always be gained if more is needed – a stark difference from the working class. For another, money is converted into real assets – business empires, beautiful aesthetic works of art or architecture, vineyards and natural reserves, and so on. Real places and things that can’t just be taxed or inflated away.

Bear with me as I indulge some personal stories. I hope they are demonstrative. I once met a seemingly ordinary Australian man who had come from good money, and for whom money came easily, and I made the typical mistake of a working man’s son in asking him where he invested – after all, that’s what the gurus tell us that all wealthy people do, right? To my surprise, he didn’t invest it anywhere. He did not own a single stock or share. After all, he said to me, why trust someone else to use his money better than he could? If he had spare money, he’d fire up another small business and get it going. It was a shock to me. My father, strict about his finances and counting every precious cent, too suspicious to even delve into bluechip stocks, had unwittingly engendered in his children that money was hard to come by, and probably just as well given it was also the root of all evil. But he had also taught us that businesses were necessarily hard, unforgiving graft, and much too risky. It was a lesson that had been well-meant, but ill-learned.

I once met a German countess of a famous industrial family. She was the second child of the fourth-in-line son. She had never wanted for anything, even so removed from the immediate succession. Through her I learned that the family did not simply own their industrial namesake – which alone would be enough to settle anything. They had wineries, collections, properties on every continent, and various other elite services that you or I could never afford. Through my conversations with her I learned that past a certain amount of wealth, it was difficult to actually, practically, lose money in the day-to-day of owning these assets. The easiest way to lose it, which I learned from her direct experiences, was from misjudgements of breeding. Someone who knew nothing about money getting into their family was enough to cause a lot of trouble, and I saw it happen albeit briefly.

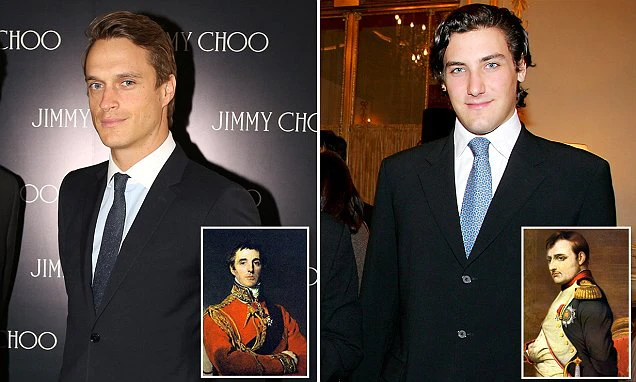

The heirs of Wellington and Napoleon are both wealthy traders in London. Even dispossessed nobles still own much of their old property – they are simply dispossessed of political power. They have a royal claim to that, but no physical armies to back it up.

Now one last story – let me tell you about the middle class Englishman I met. He was a young man my age, living in a shared flat in London, and worked his job to the best of his ability. It was a niche job for which he had developed a very good set of skills. Thinking he could easily market himself and carve out his own little aristocracy, I asked him if he had ever considered going into business for himself. No, he told me, while he had thought about the whole thing, it was simply too much bother. Managing all that was just a lot more work than he really cared to do. Mind you, he often worked until 9 or 10 PM. His only hobby was going drinking with mates. Couldn’t he have used that time differently? Rather than working for someone else until late, why not manage business affairs? I didn’t ask him this, but respected where he was coming from. After all, it isn’t wrong to simply be content.

For many people, all that differentiates them from inherited nobilities is attitude. You would be surprised to know just how many people have specific skillsets that they could market for themselves and become wildly successful with. Even people who have common skills are able to do something great and lasting, because there are very few people out there who really believe that they can. What separates them from the rest of us is not blood or breeding – not initially – rather, the tempered fire of someone who has the drive not for fast cars and casinos, but for building high castles and old lineages. There is the drive for wealth that fuels hedonism, and then there is the drive for wealth that will last for many lifetimes.

Originally published at Mike Rusade’s Micro Crusade.