From Patriotic Alternative.

From Patriotic Alternative.

Matthew Lovecraft

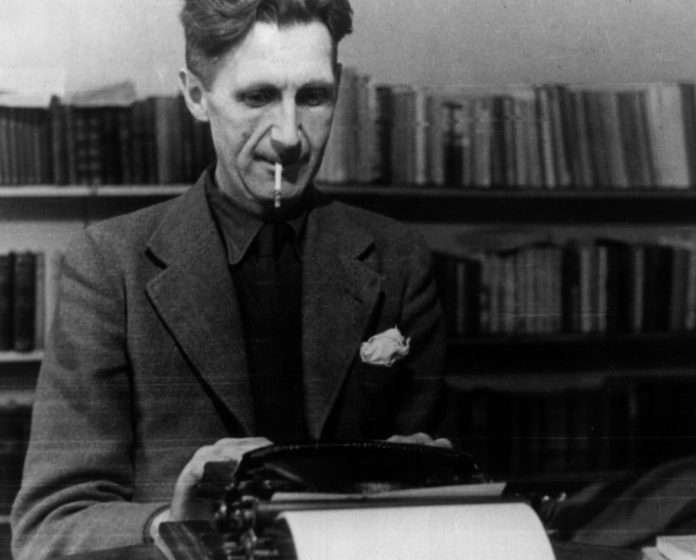

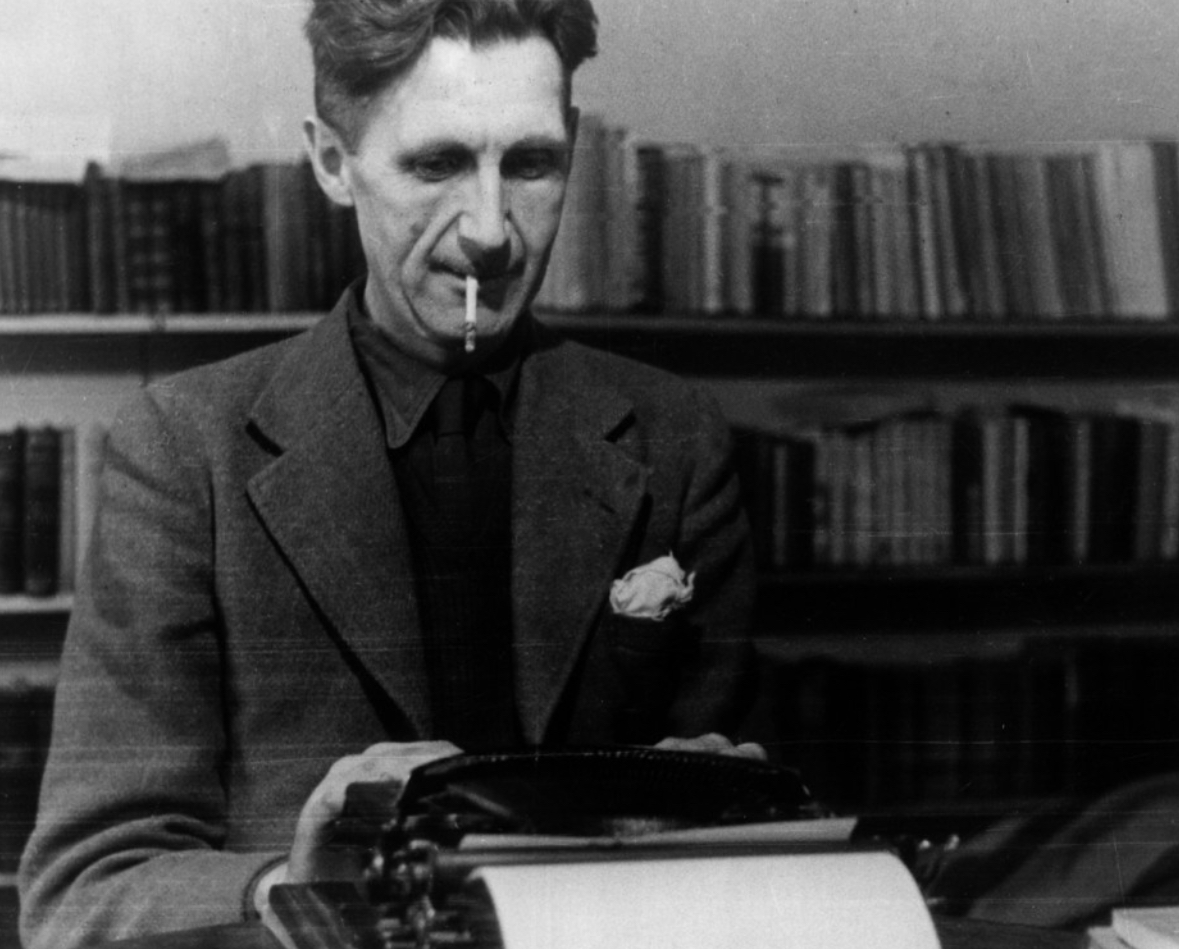

George Orwell is probably best known for two of his novels in particular: that published in 1949, Nineteen Eighty Four, based on what he imagined as a future nightmarish totalitarian dystopia; and Animal Farm (1945), the thinly disguised ridicule of Stalin’s Soviet Union. Both novels said something of Orwell’s own experiences and his subsequent disillusionment with the political Left-wing. These writings also articulated his fears as he looked forward to the post-World War II years and the second half of the twentieth century.

In addition, Orwell wrote numerous short pieces, many characterised by their political and cultural insights. One of the most well-known is his England Your England (1941) which revealed his own seemingly contradictory views that attempted to hold together his socialist convictions on the one hand, and his clear English patriotism on the other. The essay is also interesting in the way in which it brought these themes together with a profound critique of the English Left-wing intelligentsia of his time, the latter being a subject Orwell regularly touched upon elsewhere in his writings. While Orwell could subscribe to many of the socialist views of the intelligentsia, he was scornful of both its lack of patriotic convictions and contempt for the working class it purported to support. England Your England, then, is worth reflecting on – and there are other of his essays too – in which he seemingly also speaks to us on such matters in these uncertain times we live in.

First, consider Orwell’s patriotism. In this respect he is at pains to separate patriotism from the more aggressive and expansive forms of nationalism obsessed with the acquisition of power. It was his loathing of the authoritarian manifestation of Franco’s nationalism in Spain of the 1930s that drew him to fight for the Republican forces and join Leftist elements – Stalinists, Trotskyist, socialist, anarchists among them – a short lived coalition that crumbled under internal rivalries as the country’s civil war unravelled.

Definitions

Orwell’s definition of nationalism which he viewed as a malignant force, espoused most cogently in his Notes on Nationalism (1945), is somewhat muddled, confused, and so broad that contemporary political scientists would probably challenge its main criteria. Whether his definition is workable or not, Orwell distinguished aggressive nationalism from patriotism. Patriotism was, for Orwell, about love of country and he loved his country, England, despite its profound class divisions and the acute social inequalities that he observed. Thus, he cared desperately about the English working class as noted in another of his famous works, The Road to Wigan Pier, detailing the appalling conditions – the mass unemployment, poverty and slums – under which that class toiled and lived. But Orwell noted that, despite their social environment, it was a class which was inclined towards patriotic loyalties which, in reality, turned out to be a more constructive and authentic form of nationalism.

Orwell further defined patriotism in his Notes on Nationalism:

“By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force upon other people.”

In England Your England Orwell outlines the significant and impact of patriotism, claiming that it was no trivial matter. It is worth quoting what he had to say at length:

“One cannot see the modern world as it is unless one recognizes the overwhelming strength of patriotism, national loyalty. In certain circumstances it can break down, at certain levels of civilization it does not exist, but as a positive (emphasis original) there is nothing to set beside it. Christianity and international Socialism are as weak as straw in comparison with it. Also, one must admit that the divisions between nation are founded on real differences of outlook. Till recently it was thought proper to pretend that all human beings are very much alike, but in fact anyone able to use his eyes knows that the average of human behaviour differs enormously from country to country. Things that could happen in one country could not happen in another.”

The essential elements of patriotism and its enduring appeal and the virtues of an organic national and cultural loyalty, Orwell insisted, was a fact that the Left-wing intelligentsia failed to recognise. This was a tendency, he suggested, particularly evident among the English intellectuals with their engrained hatred for country, King, and empire. In England Your EnglandOrwell observed that:

“The mentality of the English Left-Wing intelligentsia can be studied in half a dozen weekly and monthly papers. The immediate striking thing about all these papers is their generally negative, querulous attitude, their complete lack at all times of any constructive suggestion. There is little in them except the irresponsible carping of people who have never been and never expect to be in position of power. Another marked characteristic is the emotional shallowness of people who live in a world of ideas and have little contact with physical reality. And underlying this is the really important fact about so many of the English intelligentsia – their severance from the common culture of the country.”

Orwell continues:

“In intention, at any rate, the English intelligentsia are Europeanized…. In the general patriotism of the country they form a sort of island of dissident thought. England is perhaps the only great country whose intellectuals are ashamed of their own nationality.”

In a further essay, James Burnham and the Managerial Revolution (1940), Orwell noted that the English intelligentsia, at the height of the Second World War when prospects looked bleak for Britain, were far more defeatist than the mass of the population. He thus saw the intelligentsia as “chipping away” at English morale and morality, stating that “Within the intelligentsia, a derisive and mildly hostile attitude towards Britain is more or less compulsory.” In his time Orwell sensed the decay of the British empire partly due a stagnating military middle class, adding “.… but the spread of a shallow Leftism hastened the process.” Moreover, he insisted at the same time that the attitude of the Left-wing intelligentsia towards the Stalin’s totalitarian Soviet Union was one of “genuinely progressive impulses mixed up with admiration and cruelty”. This was accompanied by what Orwell discerned as widespread anti-Semitism among the ranks of the intellectuals.

Bourgeois elitists

This Left-wing intelligentsia, needless to say, were not drawn from the English working class they claimed to support. Orwell referred to such people in various places in his writings as the “Bloomsbury highbrow” and “the pansy-life circles”. In short, they were little more than well-healed bourgeois elitists. He also spoke of the ingrained Anglophobia of Left-wing parties insisting that, in turn, themselves often reflected the hypocrisy of the Left intellectuals. As he writes in his essay Rudyard Kipling (1941):

“All Left-wing parties in the highly industrialized countries are at bottom a sham, because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not really wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life which those aims are incompatible.”

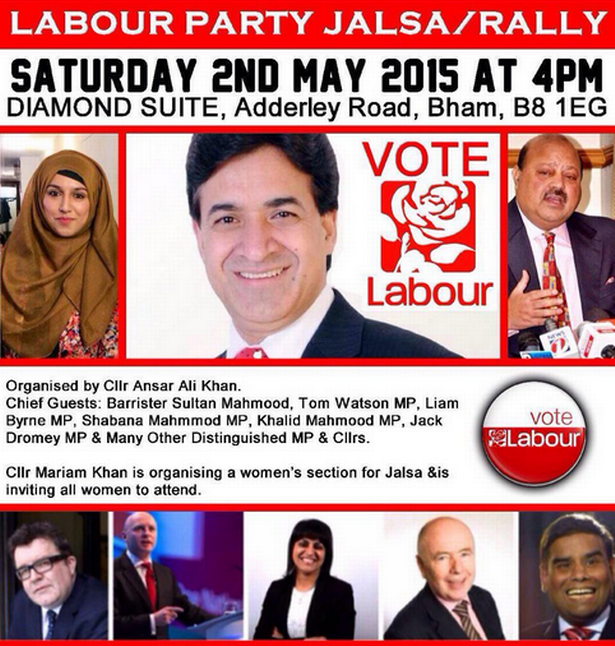

What would Orwell have made of his subject matter in the political atmosphere of today: patriotism, the working class, the leftie intelligentsia? Some matters he spoke of have changed but not others. He would no doubt have noted that segments of the English (indeed British) working class and the Labour Party that historically support it are increasingly going their own different ways. One development is that many in the working class are more affluent or at least feel affluent and as a result have increasingly voted Tory since the Thatcher years. To this, more recently, there is the matter of Labour’s resistance to Brexit, so that in the 2019 general election many traditional Labour seats, including poorer sections of the working class, fell to the Tories as the so-called Red Wall across northern England crumbled.

The other dilemma for the Labour Party and the Left in general is that the size of the working class as a component of the British population has dwindled, especially as the nation’s industrial base and subsequently working class communities collapsed in the face of neo-liberal policies of recent governments. To win political power, explained leading Left-wing intellectuals (and not just the British variant), the Leftist parties had to solicit the support of minority and “oppressed communities” to be found in all classes in forging a coalition to propel Labour into power: women, immigrants, LGBTQ sorts and other minorities (there is certainly a dilemma in holding these groupings together of course) – to be won over by identity grievance politics and a curious mix of liberally infused human rights and the old socialist “progressive” imperative. Both liberalism and socialism have no room for meaningful and authentic patriotism of a particular ethnic people: the white indigenous British. Labour Party conference speakers are now less likely to be trade union leaders with true working class roots and more likely to be queer as folk people, gender confused types, rampant feminists, middle class environmental nut jobs and adherents to the religion of perpetual peace and harmony, each of whose identities clinging to imagined oppression rather than any commitment to patriotic loyalties.

It has often been said that it is not so much a matter of Labour voters have departed the party but that the Labour Party has betrayed the working class, subsequently the party has left it feeling increasingly alienated. In the context of multi-culturalism the white working class became marginalised and neglected – to the cost of the Labour Party. For the Left-wing intelligentsia all cultures are to be welcomed, embraced and valourised. Except one: that of the white working class. And what has not changed are key elements of much of that class’s core culture. One such element is that it is not easily duped by spurious claims that “diversity is our strength” or “Britain has always been a country of immigrants”. Orwell claimed all of those years back, in so many words, that the genius of the working class was that it could smell manure a mile off. He claimed that it “blew raspberries” at radical Left-wing manifestoes and platforms as much as it did at the rancour of dictators and Prime Ministers.

Much of the political orientation become clear as many working class people voted for Brexit. This was to the derision and of the condemnation of the Left-wing intelligentsia who were convinced they knew better. The “leave” the European Union vote was about patriotism and resisting mass immigration, as much as democracy and national sovereignty. The intelligentsia failed to understand this, despising the white working class bloke with his white van and the English flag draped from the front of the house that he bought from the local council back in the ‘80s. The intelligentsia saw only stupid peasants, the ‘gammon’, who were inclined to wander off the plantation, kept departing from the revolutionary path as identified by the Left. They don’t know what’s good for them. Uneducated stupid bastards that don’t know their own interests! If only they read Marx, Trotsky and Marcuse!

Us and them

The Leftie intelligentsia has not fundamentally changed since Orwell wrote. Its ideology may have evolved from conventional Marxism into cultural Marxism with an input from radical feminism, Foucault waffle, intersectional wokery and rampant bourgeois hyper-liberalism. But this elite still hates British patriotism, particularly English patriotism. It is comprised by “nowhere people” who seek the like-minded across borders (and preferably without borders). Everywhere they see “us” and “them”. Elsewhere, in his essay Politics and the English Language (1946), Orwell includes a discussion of “meaningless words”. One such word, he pointed out, regularly used by the intelligentsia was that of that of “Fascism” which, he said was used to describe everyone and everything they disliked and everyone who disagreed with them. Nothing has changed in this respect. Neither, it seems, has the Left intelligentsia abandoned anti-Semitism.

This intelligentsia is a closeted elite. For the “Bloomsbury highbrow”, Orwell spoke of, now substitute the “Islington set” in London and similar oligarchies to be found in other metropolitan areas and they often dominate local Labour Party leaderships. Middle class university educated Momentum types. They fail now, just as they did in Orwell’s time, to understand the patriotism of the English working class and unable to realise that they are out of touch with it. It is an elite lacking self-awareness, unable to reflect on its own failings. The poverty of their so-called intellectual thought cannot recognise this because it cannot see outside of its own international worldview in which it is entrapped in a globalised world and, ironically, dovetails with the interests of corporate capitalism. The intelligentsia continues to entertain utopian fantasies not embedded in sense of reality since it rarely recognises the virtues of the nation state, borders, tradition and moral culture.

Orwell is remembered because he turned political writing into an art. People of different ideological perspectives have emphasised various aspects of his writing which suit them. But perhaps above all, he is remembered because of prophetic talents that predicted a growing totalitarianism in the modern world. For instance, the threat to freedom of speech now evident even in so-called liberal democracies. Some seventy years after he penned the work England Your England many of Orwell’s insights remain valid for patriots. He was, of course, an internationalist himself, with sympathy for the working class elsewhere besides England. However, Orwell would probably have been a Brexiteer as were later “Old” Labour socialist in the 1960s and ‘70s. He remained a patriot to the end. He loved the country pub, the Sunday roast, ‘saucy’ seaside postcards, the moderate temper of the English. This is why his England Your England is written in honour of the English. In it he shows an understanding that layers of national experience, history and culture do matter. Much of this continues to be maligned by the Leftish intelligentsia who are attempting to make their loathing of the nation’s culture mainstream. Here is our struggle. English culture, as described by Orwell, cannot be reinvented in these times, but it can be rediscovered if we dig deep enough – including the inspiration of the writings of a great English author.