From Patriotic Alternative.

By Carl Wilkinson

Saturday 27th November marked the 89th anniversary of the Holodomor, an atrocity which took place between 1932 and 1933 in the then Soviet province of Ukraine. It is a historical event that is important to remember, because it is still pertinent today, especially for nationalists.

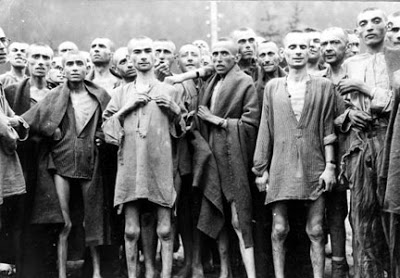

The Holodomor (literally death by hunger, in Ukrainian) resulted in the mass killing of some 3.5 to 10 million Ukrainians for the “crime” of wanting to preserve their own ethnic, national, and cultural identity. It was the consequence of the Soviet Union’s ideology of Internationalism and its policy of Russification – the goal being the destruction of the very idea of Ukraine itself.

As early as 1930 the Soviet secret police where busy targeting Ukrainian nationalists, academics, and other politically incorrect dissidents, “disappearing” them. We know this only because of the mass graves that have been discovered around cities such as Kyiv, some containing up to 200,000 bodies. Not much is known about these brave ethnic Ukrainians, in some cases not even their names; a true testament to the ruthless and callous efficiency of an authoritarian Left Wing regime in pursuit of the flawed utopian dream of equality.

The murderous events preceding 1932 had in fact shown the Soviet’s deep misunderstanding of nationalism and where it originates; the regime believed that all it needed to do was wipe out the history of Ukraine and those it deemed the bearers of it, but as the Ukrainian nationalist movement grew it quickly dawned that the true nature of nationalism was in fact bottom up and not top down.

Persecution of Kulaks

At first Stalin ordered the acceleration of collectivising farms into communes, between 1931 and 1932, which led to the cruel and unjust persecution of the Kulaks – a community of some 1.5 million farmers and their families. During this time one third had been arrested and deported from 11 regions. The main drive of this policy was to prevent any sort of insurrection, which Stalin now believed would come from the Kulaks after previously believing it would be the academics.

As nationalist sentiment grew, Stalin began to target the communes themselves. From the 18th November 1932 the communes were required to hand over all grain the farmers had previously earned for themselves, leaving them with none to eat – a task that state police and true believerswhere more than happy to carry out. Within a few days Stalin ordered that all those who did not meet their quotas had to surrender any remaining livestock too. A week later any communes that failed to meet these demands were placed on blacklists, and blacklisted communes had no right to trade or receive deliveries, meaning food production could not continue.

That same November it was announced that the Ukraine would be responsible for 1/3 of all Soviet grain supplies, and it was proudly proclaimed that “the Soviet state would fight “ferociously” to fulfill the plan”.

By December, Stalin’s security chiefs had terrorised Ukrainian officials into complete compliance by accusing those who did not meet the required quotas of treason and threatening them with execution.

In January 1933 the borders were closed and some 190,000 Ukrainians were forced to return to their villages and face the brutal prospect of starvation. Although it was offered, the Soviet regime callously rejected foreign food aid. This, combined with the previously mentioned mass executions, makes it clear what the aim of the policy really was.

If the progressive Soviet regime could not destroy the idea of Ukrainian Nationalism, then it would destroy the ethnic Ukrainians themselves – a fact many Left leaning academics today would like to wipe from history. It’s a very bitter pill for them to swallow that more ethnic cleansing took place under a Left Wing “progressive” government than any other.

For nationalists, it’s important to remember the Holodomor because of what it represents – an attempt at the complete and wholesale destruction of a nation state, something which can only be achieved by the eradication or replacement of its indigenous people. Progressives know that nationalism is not theory or method; it’s emotional, spiritual and organic and comes from nature itself. For this reason nationalism will always be a threat to those who wish to condition man into becoming the fulfilment of Marx’s doctrine.

In the shadow of the 89th anniversary of the Holodomor we remember the resolve and courage of the Ukrainian people who, despite the relentless efforts and policies of forced starvation by the Soviet state, prevailed and lived. Today they enjoy national sovereignty, but more importantly, they enjoy and celebrate their identity as ethnic Ukrainians.