Originally published October 15, 2016. Enjoy these days of Weimar Australia.

From an anonymous contributor

If you’re like me, you might have wondered where and when modern Leftism originated. You’ve probably heard a few ideas and a few names tossed about.

But sometimes you wonder, why are they so irrational? Why do they hate reasonable debate? Why are they so darned angry? What’s with all the swearing? Why is academic writing so bad? Why are they so emotional, and why do they love ugliness? Why are they so fond of hedonism, drugs, and homosexuality? Why are they so fond of topsy-turviness?

Stefan Zweig was an Austrian, secular Jewish, upper-middle class writer who was born in the Belle Époque; the ‘beautiful epoch’ of peace and prosperity in Europe between the Franco-Prussian War and the Great War. He was a 1st-wave feminist, artistic and sensitive, pacifist, married twice, had gay friends, and was not hostile to communism (though not a communist himself); he was that era’s version of a progressive. He lived through World War One, watching firsthand as his prosperous, lovely, free country was ruined by that war. He wrote all through that time, but achieved his highest popularity during the Weimar Republic period; in other words, between the end of World War 1, and the ascension of Hitler’s NSDAP in Germany in 1933. When the Nazis were in power, Zweig’s books were banned. When they took over Austria, he fled to London. When World War 2 commenced, and the bombs began to fall on London too, he fled for the Americas, winding up in Brazil in 1942, where finally, in despair, he and his wife killed themselves.

Before he did, he finished his last book, called The World of Yesterday. It’s a memoir, and also an eyewitness account of how Europe slid from what seemed like a golden era into destruction and totalitarianism, in such a short time. It’s an invaluable piece of primary-source evidence, and it provides some insights into the questions I asked above.

Broadly, before the war, Austria and Germany had been cultural centres. Artists and intellectuals were abundant in Vienna and Berlin before the war. But by 1919 youth, particularly Austrian and German, were utterly cynical of the old ways, which had brought them the Belle Époque, but had then brought them the Great War. Why would they do anything the old way? What other response could there be but reversal of everything? And then, the humiliation of hyper-inflation made everything worse.

Broadly, before the war, Austria and Germany had been cultural centres. Artists and intellectuals were abundant in Vienna and Berlin before the war. But by 1919 youth, particularly Austrian and German, were utterly cynical of the old ways, which had brought them the Belle Époque, but had then brought them the Great War. Why would they do anything the old way? What other response could there be but reversal of everything? And then, the humiliation of hyper-inflation made everything worse.

Here are some quotes from the book. All boldface is mine; these are things which particularly relate to issues in Australia in 2016 which I wanted to highlight; Safe Schools, same-sex marriage, etc. All quotes are from the 1953 Hallam edition, published by Cassell & Company, Ltd.

“Small wonder, then that the entire youthful generation looked with exasperation and contempt at their fathers who had permitted first victory, then peace (i.e. President Wilson’s first peace plan) to be taken away from them; who had done everything wrong, had been without prescience and had everywhere miscalculated. Was it not intelligible that the new generation lost every trace of respect? It doubted parents, politicians, teachers; every decree, every proclamation of the state was read with a dubious eye. The post-war generation emancipated itself with a violent wrench from the established order and revolted against every tradition, determined to mould its own fate, to abandon bygones and to soar into the future.

“It was to be quite a new world in which fresh regulations were to govern every phase of life; and, as was to be expected, the new life began with gross excesses. Anybody or anything older than they were was put on the shelf. Children as young as eleven or twelve went off in organized Wandervögel troops which were well instructed in matters of sex, and travelled about the country as far as Italy and the North Sea.

“Following the Russian pattern, “pupils’ councils” were set up in the schools and these supervised the teachers and upset the curriculum, for it was the intention as well as their will to study only what pleased them.

“They revolted against every legitimated form for the mere pleasure of revolting, even against the eternal polarity of the sexes. The girls adopted “boyish bobs” so that they were indistinguishable from boys: the young men for their part shaved in an effort to seem more girlish; homosexuality and lesbianism became the fashion, not from an inner instinct but by way of protest against the traditional and normal expressions of love.

“The comprehensible element in everything was proscribed, melody in music, resemblance in portraits, intelligibility in language.

“In that epoch of wild experiment in every field everybody desired to surpass, at a single impetuous leap, whatever had been achieved in the past; the younger one was, the less he knew, the better he suited the situation because of his freedom from all tradition: at last youth’s vengeance against the world of parents raged itself out triumphantly.

“Nothing was more tragi-comic in this riotous carnival than the attitude of the elder intellectuals who, in a panic of fear of being considered behind the times, rushed desperately to the cover of an artificial egregiousness and dragged themselves through devious paths in the hope of keeping up with the procession. Respectable, proper, grey-bearded academicians painted over their now unsaleable still life with symbolic cubes and dice, because the young curators—they had to be young, and the younger the better—regarded all other pictures as too “classic” and were removing them from the galleries to the basements. Writers who had used plain, direct language for decades obediently hacked their sentences apart and excelled in “activism”, complacent Prussian Privy Councillors expounded Karl Marx from their lofty university seats, old-time ballerinas in a state of undress performed stylized gyrations to Beethoven’s Appassionata and Schönberg’s Verklärte Nacht.

“Every extravagant idea that was not subject to regulation reaped a golden harvest: theosophy, occultism, spiritualism, somnambulism, anthroposophy, palm-reading, graphology, yoga and Paracelsism. Anything that gave hope of newer and greater thrills, anything in the way of narcotics, morphine, cocaine, heroin found a tremendous market; on the stage, incest and parricide, in politics, communism and fascism, constituted the favoured themes; unconditionally proscribed, however, was any representation of normality and moderation.

“But I would not for anything wipe out that era of chaos, neither from my own life nor from art in its onward movement. (pp 299-301)

“But already (in 1919) there were groups strong in (Germany) that knew that they would secure followers only by assuring the vanquished people again and again that they really were not vanquished and that negotiations or compromises were treason to the nation. Already the secret organizations—strongly under homosexual influence—were far more powerful than the then leaders of the republic suspected and the latter, in their conception of freedom, gave free rein to those who sought to do away with freedom in Germany for good. (p 310)

“(Hyper-inflation in post-war Germany) produced such madness in such gigantic proportions. All values were changed, and not only material ones; the laws of the State were flouted, no tradition, no moral code was respected, Berlin was transformed into the Babylon of the world. Bard, amusements parks, red-light houses sprang up like mushrooms… Along the entire Kurfürstendamm powdered and rouged young men sauntered and they were not all professionals; every high-school boy wanted to earn some money, and in the dimly lit bars one might see government officials and men of the world of finance tenderly courting drunken sailors without any shame. Even the Rome of Suetonius had never known such orgies as the pervert balls of Berlin… In the collapse of all values a kind of madness gained hold particularly in bourgeois circles which had been unshakeable in their probity. Young girls bragged proudly of their perversion, to be sixteen and still under suspicion of virginity would have been considered a disgrace in any school of Berlin at the time, every girl wanted to be able to tell of her adventures, and the more exotic the better. (pp 313-314)

“But the most revolting thing about this pathetic eroticism was its spuriousness. At bottom the orgiastic period which broke out in Germany simultaneously with the inflation was nothing more than feverish imitation; one could see that these girls of decent middle-class families would much rather have worn their hair in a simple arrangement than in a sleek men’s haircut, that they would much rather have eaten apple pie with whipped cream than drink strong liquor; everywhere it was unmistakeable that this over-excitation was unbearable for the people, …(who) actually only longed for order, quiet, and a little security and bourgeois life. (p 314)”

***

Now, you could argue that the above is just one man’s subjective view of history, that he may have been mistaken about some things, and that a history which quotes from more sources would be more balanced and accurate. And you’d be right.

But there is something truthful in the basic idea: in 1919 civilised, advanced Europe had torn itself to shreds after four and a quarter years of horrifying carnage and self-mutilation. It would be tempting for any person in that time, especially one on the losing side, to abandon the old ways and traditions, when those same old ways and traditions had led to unprecedented destruction and humiliation. Why not go topsy-turvy in those circumstances? Why not create brand new values that were the opposite of the old ones? If there’s nothing to live for or work towards, why not live for pleasure and do what you will?

“Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” Well, in those circumstances, why not?

And does it not seem that the Left’s values of 2016, one of which is constantly to reject the old traditions, are not that far away from those new ‘values’ of Germany and Austria in 1919?

But I wonder, can man create his own values? The Left of 2016 thinks so, and seems to have thought so in 1919, too. But are human values really subjective, as the Left thinks, or are they objective? Are they as firm a law of nature as the law of gravity, or can you change them up every few years?

It’s a topic for another essay. In any case, it seems like 1914-1919 was a critical time in the history of Western civilisation, of which Australia is a part. From 1914 on, things in the West were never going to be the same again; and in 1919, in the ashes of the defeated European countries, some strange new notions about how to be human arrived. Those notions changed and developed in the almost century since, and went to America and Australia, but never went away.

Lest we forget.

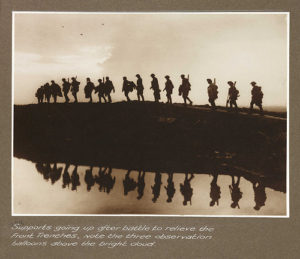

Photo by National Media Museum