Kenny Liew

Like most slogans from social justice warriors today, the call for the abolition of negative gearing is designed to virtue signal rather than to actually consider the practicality and consequences of such a proposal. It is a catchphrase which decides whether one is compassionate or a greedy, evil capitalist. However, a more sustained look at the issue of negative gearing counters the prevailing media narrative.

Negative gearing refers to the deduction of interest expenses on money borrowed (geared), in the purchase of an investment property, from the taxable income of the investor, in particular when the interest expense exceeds rental income (negative). There is nothing contentious about this. It is settled in taxation law that income is taxable, and the expenses earned in assessing that income are deductible from that income. Negative gearing has been part of the tax code since there was a federal tax code in the 1930’s. Therefore, it is false to claim that negative gearing is a cause of housing un-affordability over the last thirty years. If indeed negative gearing is the scapegoat then one would also have to blame the original Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 that harmonised a federal income tax for the first time in Australian history. It is common sense that taxation causes housing un-affordability by decreasing disposable income.

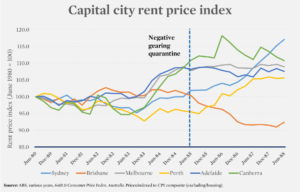

In fact, all that happened thirty years ago in July 1985, was that the Hawke/Keating government experimented with abolishing negative gearing in order to increase tax revenues to support the burgeoning federal deficit. This was short-lived and the legitimate deduction was quietly returned in September 1987 after rental prices rose. This is unsurprising because renters form the other side of the transaction with investors. An attack on investors, once you follow through the logical and empirical evidence, is an attack on renters. When investors leave the property market, there will be less construction of new homes and less conversion of owner-occupied housing stock to the rental market. As Bob Hawke puts it in a post-budget dinner on 16 September 1987, the ‘restoration of negative gearing, and retention of a still generous depreciation allowance should combine to provide a powerful boost to the supply of rental accommodation, thus pushing rents down in real terms over time.’

One counter argument is that the rental feedback is over-exaggerated. Saul Erlslake claims that rents increased only in Sydney and Perth due to a lack of vacancy in those cities. However, all that argument is saying is the uncontroversial fact that there are many factors affecting rent. This does not undermine the logic nor do away with the empirical evidence from Sydney and Perth. In fact, one could say that once you control for vacancy, as in the case of Sydney and Perth, the abolishment of negative gearing will lead to an increase in rental prices.

Since renters are often the young, single mothers, the poor; the abolishment of negative gearing merely transfers the burden of housing from richer home-buyers, who have a significant cash deposit and an income worthy of a mortgage; to renters, who do not. The problem of affordability does not go away. It merely shifts to a silent and poor minority who are unable to save the difference in order to move up the ladder of opportunity.

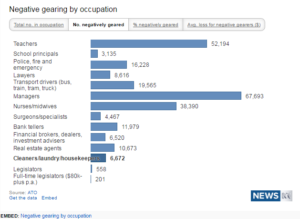

Not only does abolishment transfer wealth from the poor to the middle class, it transfers wealth from the middle class to the rich. For negative gearing only applies to small time investors in their first foray into a large investment as they try, in the short term, to build a tax-effective asset to save more of their income from personal exertion; and after paying off the investment mortgage, are looking long term at building a more financially independent life. Sinclair Davidson observes that the median Gross Total Income for all Landlords (all income before any business or personal deduction) was $78,618. They are predominantly nurses, teachers and child carers, managers, midwives and aged care workers, emergency service workers and clerical staff.

Meanwhile, the rich do not need negative gearing. The rich do not, relatively, derive their income from personal exertion but rather from multiple passive investments and businesses. They positively gear – no one gets really rich by negatively gearing (aka. making losses) forever. Quarantining income does not affect them as they invest through corporations and trust structures that do not pay the highest marginal tax rates. They have the best professional accountants and lawyers to advise them. Even if the government ‘successfully’ closes all ‘loopholes’, such investors simply move to other investments (say, the share market) or offshore (with further implications on the rental market). Thus, if one is concerned about the Gini coefficient, this is one of the worst proposals to suggest for the middle class will be unable to catch up to the rich.

Rather than playing off the rich against the middle class and then playing the middle class against the poor, we ought to be looking at the real causes of housing un-affordability. Firstly, the crisis is a result of factors beyond our control. Sydney is a city in a basin surround by sea, plateaus and mountain ranges. We are therefore constricted in our supply of land to build houses. This restriction has always been there since settlement but it probably took the baby boomers to finally discover our limits in the 1980’s.

Rather than playing off the rich against the middle class and then playing the middle class against the poor, we ought to be looking at the real causes of housing un-affordability. Firstly, the crisis is a result of factors beyond our control. Sydney is a city in a basin surround by sea, plateaus and mountain ranges. We are therefore constricted in our supply of land to build houses. This restriction has always been there since settlement but it probably took the baby boomers to finally discover our limits in the 1980’s.

Secondly, this crisis is a result of our own decisions. If we want a city surrounded by nature and pristine forests then this will cost. To the north and south, what land we can build on is covered by the great national parks leaving only specific corridors to build. We could solve this land shortage by building higher and create a Hong Kong style population density but most of us want a backyard. We want to live close to the city. We want bigger houses, air-conditioning and Caesarstone bench tops. We want better transportation and infrastructure to the tune of $20billion. Regrettably, we increasingly choose to live alone. These decisions all cost. And to pay for them we have to do what previous generation did – a combination of patience, increasing your income (e.g. by getting a good job), decreasing your expenses (don’t go on overseas trips and eat a modest breakfast) and being realistic. There are no simple answers here, suffice to say that life is a series of trade-offs that we choose, but at least they are a product of our own choices.

What is less justifiable is when the crisis is also the result of government decisions. As David Leyonhjelm recently pointed out, the NSW state government collects $8billion in stamp duty each year despite promising to abolish it in the advent of the GST back in 2000. To buy a Sydney house at the median price of $850,000, you need an additional $33,000 in stamp duty. Further, instead of releasing land to ‘make residential land available at the lowest price practicable’ as designed to in the 1970’s, the law now requires it to maximise net worth for the State Government. Naturally, Urbangrowth (formerly the Land Commission) which drew in revenues of $658 million, purposefully restricts the release of land in order to drive up the price. All this along with passing development costs to developers and land taxes ($3 billion) further creates a higher cost base that’s passed on to home buyers, investors and renters.

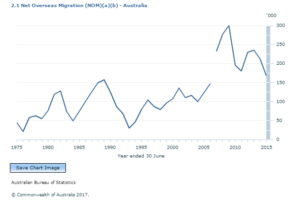

While the State government restricts supply, the Federal government stokes demand by continuing mass immigration even though many Australians are asking for a reprieve from the stresses of increasing congestion, competition and crime. In the last thirty years, we have had unprecedented migration, with most settling in Sydney. This, along with the Federal government’s dependence on foreign investment and the Federal Reserve’s artificially low interest rates create an insatiable demand for real estate.

This housing affordability crisis therefore is in some ways normal because of the nature of the city and because of our own choices. Sydney is expensive to live in because a lot of us want to live here and to a certain style we are accustomed. This is something we all have to tackle individually and together as we consider what sort of a nation, city and family we want to be. The State and Federal government however could help us by not interfering with the supply of land and housing; and not artificially boosting demand through immigration. The media should be aiding this conversation by going through the facts and the pros and cons of various proposals. The demonisation of negative gearing is a distraction from that conversation.