BJ

On the 19th of December, the Electoral College will meet to officially elect the next President and Vice President of the United States. The Electoral College is made up of 538 individuals as electors, and a majority of 270 electoral votes is required to elect a President and a Vice President. The votes cast in the Electoral College are counted in a joint session of Congress on the 6th January. The result of the election is not official until the Electoral College has voted and the votes are counted in the Congress.

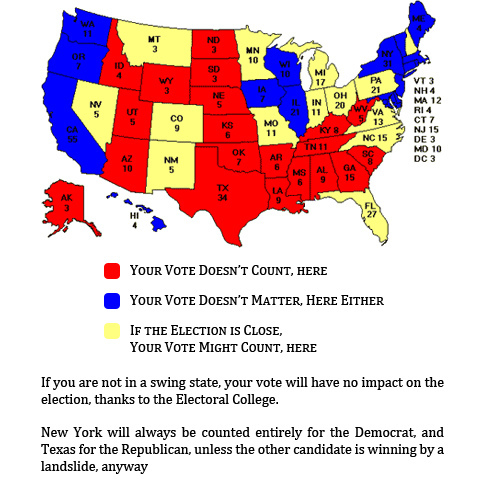

The electors come from each state, and under the 23rd Amendment to the US Constitution, from the District of Columbia, which is for this purpose treated as if it is a state. Electoral votes are allocated to states based on the number of Senators and Congressmen from that state, which is in turn a function of the population determined in the last census, taken in 2010. It follows that the most populous states have more Senators and Congressmen, and therefore they have a larger number of electoral votes in the Electoral College; New York has the largest number with 29 electoral votes, and, at the other end of the scale, a number of states with smaller populations have only three.

The electors come from each state, and under the 23rd Amendment to the US Constitution, from the District of Columbia, which is for this purpose treated as if it is a state. Electoral votes are allocated to states based on the number of Senators and Congressmen from that state, which is in turn a function of the population determined in the last census, taken in 2010. It follows that the most populous states have more Senators and Congressmen, and therefore they have a larger number of electoral votes in the Electoral College; New York has the largest number with 29 electoral votes, and, at the other end of the scale, a number of states with smaller populations have only three.

In every state, each Presidential candidate has a group of electors chosen by their party. When the states hold their elections, the votes cast for the Presidential candidates are actually used to choose between the various tickets of electors, chosen by the political parties, to be the state’s representatives as its electors in the Electoral College. In most states, the Presidential candidate who wins the most votes takes all of the electors for that state, although Maine and Nebraska allocate their electors based on the proportion of the votes won by the each Presidential candidate.

The Electoral College sounds unnecessary, and arguments periodically arise about the fairness of the process – most often when a Presidential candidate wins the popular vote, but does not obtain sufficient electors in the Electoral College to become President, which is the position in which Clinton finds herself. The disappointed then claim, often loudly and indignantly, that the President should be the person who obtains the most votes, and the process of the Electoral College ought not defeat them. The argument is well-worn, tired, and suffers from one major flaw. The Electoral College was the deliberate creation of the US founding fathers who, in drafting the US Constitution, sought a compromise between the two competing views concerning the method of electing the President; by a vote of Congress or by the popular vote of qualified citizens. When the history and the process are both properly understood it is clear that the Electoral College contains elements of both.

There is no Federal law that compels the electors to vote according to the results of the election in their state, and an elector in the Electoral College who does so is called a ‘faithless elector’. Among the states, 29 bind their electors to cast their vote for the winner of the popular vote in that state, under threat of fine, or disqualification and replacement by a substitute elector. In others, a vote cast by a faithless elector is rendered invalid. The remaining states do not seek to bind their electors, although when a party chooses candidate electors, they usually bind themselves by pledge to vote for the party’s candidate.

While ‘faithless electors’ are rare, there have been 156 faithless votes cast in the history of the Electoral College, the last being in 2004 when an unknown elector from Minnesota, who was pledged to vote for John Kerry, instead cast his Presidential vote for Kerry’s running mate, John Edwards.

Since Trump’s victory, there have been media reports that a group of approximately sixteen electors from states won by Clinton have been canvassing other electors not to vote for Trump and to instead cast their vote in the Electoral College for Hillary Clinton. Yesterday, the New York Times published an op-ed by one Christopher Suprun, a Republican elector from Texas, who has announced his intention to cast a faithless vote, by stating that he will not vote for Trump in the Electoral College in accordance with the result of the popular vote in Texas. That position is the last in a series of statements made by Suprun made between August and October in which he has vacillated between an intention to cast a faithless vote for Clinton and voting for Trump.

Suprun’s reasoning for his latest position is that the election of the next President is ‘not yet a done deal’ and ‘Electors of conscience can still do the right thing for the good of the country. Presidential electors have the legal right and a constitutional duty to vote their conscience.’ The latter point is certainly wrong, as the US Supreme Court has held that the US Constitution does not require that electors be free to vote as they choose and Suprun, as a Republican elector, has pledged himself to vote for Trump. It remains to be seen whether Suprun casts a faithless vote for Clinton or further vacillates, and he might now be pressured to relinquish his position as an elector for Texas, given the very public statements of his intention to defy the wishes of the voters in Texas. We will have to wait and see.

For all the excitement at the New York Times and in the Democrat strongholds, the margin of Trump’s victory means it is extremely unlikely that electors will go rogue in sufficient numbers to deny him the Presidency. And once again, the public have yet another reason to feel betrayed by the political establishment and see them as unworthy of the trust the voters have every right to expect.

Photo by KAZVorpal