C. S. Lewis, in his Narnia series, created a world of more than just talking otters, fauns, and Father Christmas. To the south of Narnia lay a desert, on the other side of which lay the vast Calormene Empire, populated by cruel, dark-skinned, turbaned warriors – who bore a remarkable resemblance to Arab or Turkish Muslims. The Calormene god was a demon with the body of a four-armed human, and the head of a bird, whose name they invoked when going into battle, “Tash, Tash, the great god Tash. Inexorable Tash.” In the final book of the series The Last Battle, the Calormenes invaded and overran Narnia.

Lewis’ friend and colleague, J.R.R. Tolkien, in his own works, depicted an idyllic rural England in The Shire, the home of the Hobbits, set in a relatively safe corner of a far from safe Middle Earth. Again to the South, there lay the kingdom of the Haradrim, a race of cruel, dark skinned, turbaned warriors, who joined forces with Sauron in his attempt to wipe out Gondor.

It is all too easy these days to write off such obvious literary allusions to the Islamic Caliphates as some old racist, colonialist throwback, or a quaint, paranoid fear of the Green Peril. But for Europe of the 1930’s, the time when Islamic empires constituted an existential threat to Christian Europe was still in living memory. This mindset, which seems so foreign to us, speaks to the remarkable success that the West achieved once it surpassed its long militarily-superior nemesis.

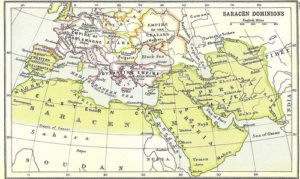

Within the “Prophet” Mohammed’s lifetime, much of the Arabian peninsula had been taken by military conquest, and by a little over a century after his death, the Islamic empire stretched from Spain and Morocco to the borders of India. The Caliphate smashed its way into France before it was stopped at Tours in 732. A Muslim army sacked parts of Rome in 846, and it took until 1488 to push it out of the Iberian Peninsula.

Within the “Prophet” Mohammed’s lifetime, much of the Arabian peninsula had been taken by military conquest, and by a little over a century after his death, the Islamic empire stretched from Spain and Morocco to the borders of India. The Caliphate smashed its way into France before it was stopped at Tours in 732. A Muslim army sacked parts of Rome in 846, and it took until 1488 to push it out of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Crusaders were able to retake Jerusalem and the Biblical lands briefly in the 11th and 12th centuries, but then Byzantium, after centuries of assault (during which time its territory had been reduced to a finger of Thracian land), fell to the Turks in 1453.

Europe’s Dark Age is generally attributed to the fall of the Western Roman Empire at the hands of the barbarian Goths. But this ignores the fact that although the Roman Empire was dissolved, the Goths largely integrated into and maintained the system of the old empire. North Africa was still essentially ‘European’ until it was overrun by the Caliphate in the 7th and 8th centuries. This loss of vast stretches of territory, and Islamic naval domination of and piracy in the Mediterranean was the ultimate cause of the dramatic plunge of Europe into poverty, decay, and disease.

Well over a million Europeans were taken as slaves to serve in Muslim empires, captured either in the process of invasion, or by raids on coastal towns. The men were used as forced labour, while the females augmented extensive harems, suffering a life of sexual slavery. The number of slaves the various Caliphates took from Africa and Asia are estimated to dwarf not only the number of Europeans, but also that of the trans-Atlantic slave trade to the Americas.

Even as Europe entered its Renaissance, the Ottoman Empire continued to expand throughout Eastern Europe and Russia, being stopped twice at the gates of Vienna, most famously in 1683. This event provides one of the best insights into Tolkien’s work. In Return of the King, Tolkien depicts the siege of Minas Tirith, the capital of Gondor, in which a cavalry charge led by the king of Rohan, whose forces come to Gondor’s aid, help to save the city from destruction. Tolkein makes it clear that the fight for Minas Tirith is not just a battle between two empires, but a battle for the survival of the human race, and all good creatures of Middle Earth.

Despite much debate among both Tolkien buffs and history buffs, this is a clear reference to the largest cavalry charge in history, led by the King of Poland, during the 1863 battle of Vienna, in which the massive attacking Ottoman force was defeated and Vienna was saved. Given that Vienna was itself the gateway to the heart of Europe, the role Vienna would play over the following two centuries as one of the fountains of European culture, and that the battle initiated the gradual, fatal decline of the Ottoman Empire, this battle is one of the most important turning points in history. Thus Tolkien not only depicted Muslim-like men fighting for the ultimate form of evil in the world, he effectively depicted these Muslim fighters as orcs.

What we can take from this depiction is that although Europe had been able to surpass, and eventually occupy, much of the land of its once seemingly invincible foe, a scar had been left deep in its collective psyche. Of course, there had been incessant conflict within Europe, just as there had been within the Arab world, and sometimes alliances between Arabs and Europeans against other Arabs and Europeans. Europe only very rarely saw itself as Europe, and much less often and to a lesser extent to which the Muslim/Arab world viewed itself. Pockets of enlightenment and intolerance existed in Christendom and the Caliphate, and atrocities were committed by both sides. But none of this can diminish the significance of the existential threat posed by a civilisation which racked up a worldwide body-count of 270 million in its 1400 year existence. Lewis and Tolkien were merely reflecting the collective cultural memory of their time, an understanding of where Europe had been, and an appreciation of just how significant its pre-eminence was, given how close it had come to destruction.

This understanding has diminished over the last century of Western domination of world affairs. We have been taught to view our colonial history as one of the greatest injustices inflicted on humankind, rather than simply one civilisation surpassing others. We have been taught to view actual injustices of the past, such as religious intolerance, slavery, and denial of the vote to women as a damning indictment of our own barbarism, rather than admiring the bravery and virtue of our ancestors who strove to overcome these injustices.

But our collective memory is finding a way to re-emerge, like the symbolism of a nightmare, in the literature of our day- television and film. Game Of Thrones has become immensely popular, despite its violence and near nihilism. It depicts a world where tyrants defeat the noble, and threats to human existence lie in every corner. And again, a race of cruel, dark skinned, often turbaned warriors lives to the south, across the narrow sea in a desert-like land.

But our collective memory is finding a way to re-emerge, like the symbolism of a nightmare, in the literature of our day- television and film. Game Of Thrones has become immensely popular, despite its violence and near nihilism. It depicts a world where tyrants defeat the noble, and threats to human existence lie in every corner. And again, a race of cruel, dark skinned, often turbaned warriors lives to the south, across the narrow sea in a desert-like land.

Zombies have replaced orcs as the threat that dare not speak its name (both for fear of inflaming the threat of Islamists, and incurring the opprobrium of the self-appointed guardians of political correctness). A common theme from Islamist terrorists is that their advantage lies in the fact that they love death as we love life. Stories from the Hadiths talk about how Muslim fighters would throw themselves into battle, seeking death, in order to be rewarded in heaven.

Likewise, zombies are depicted as having no concern for their own well-being – obsessed only with killing and eating humans, and spreading the virus within them. They will bash through glass windows with their heads, throw themselves off buildings, and charge a hail of gunfire en masse just for a bite. It is precisely this disregard for their own life/unlife that gives them an advantage over humans when they have the numbers. It is this disregard which so paralyses and decimates human civilisation, robbing it of the technology and organisation to fight it. Even more terrifying than a kamikaze aeroplane, which you can at least identify, is the idea of a threat that could come from someone who looks just like us, whether it is a zombie, suicide bomber, or just a guy with an axe.

Our society is far safer than it was a century ago, whether it be from disease, predators or foreign powers. Yet that dark scar deep in our psyche remains, and it is telling that when the actual threat has re-emerged, we have made ourselves incapable of even naming it – “this has nothing to do with Islam”.

Photo by vtdainfo

Photo by prince_volin