First off, this article is intended as a criticism of comfort. It is directed against the impulse we all share to crawl into the comfy blankets of our history and pretend that all the answers we seek are there. It is not a criticism of the traditional values of the Western world, nor is it a cynical attempt to proffer some new political system as so many have done before. With that out of the way, allow me to begin with the primary distinction in mind between Tradition and progressivism.

Progressivism is not merely moving forward for movement’s sake, nor should it be solely thought of in the way we think of it today. To be progressive is now a byword for being a liberal of the deconstructive leftmost stripe, but a glance through the policies of many so-called “regressive” or “traditionalist” political movements shows that they were for the time far more progressive than we give them credit for. It gives us a lot to think on, as some of the most radically pro-Western movements of recent history were far from what we’d expect in an appeal to traditional Western society.

There must be some acceptance among us of the nature of Westerners. We are outward-striving, constantly seeking open spaces and expansion – not just geographically or politically, but spiritually, scientifically, and mechanically. No matter what happens in the future, the footprints of Western man will forever remain on the moon, as a humble monument to our innermost nature. It doesn’t occur to most people that such ideals and strivings do not naturally appeal to other cultures, and they feel no innate need to do these great feats. There are strategic reasons behind Chinese moon probes, for example, or Indian rocket technology, but they feel no impulse to push humanity into the stars for its own sake. Were we to cease being a global power, a nation such as China would reach its zenith and simply stay there, its technology and society maintaining the current level for probably a thousand years. We are doomed simply by the fact of who we are to be constantly looking for the next horizon, wherever it may be. It is for this reason that our societies have often broken tradition, and although this rarely happens with ease, it happens more easily for us than probably any other. Within us there is some sense that the old ways cannot always bear us hence, and that isn’t just childhood liberal indoctrination but often innate, ruthless Western pragmatism.

There must be some acceptance among us of the nature of Westerners. We are outward-striving, constantly seeking open spaces and expansion – not just geographically or politically, but spiritually, scientifically, and mechanically. No matter what happens in the future, the footprints of Western man will forever remain on the moon, as a humble monument to our innermost nature. It doesn’t occur to most people that such ideals and strivings do not naturally appeal to other cultures, and they feel no innate need to do these great feats. There are strategic reasons behind Chinese moon probes, for example, or Indian rocket technology, but they feel no impulse to push humanity into the stars for its own sake. Were we to cease being a global power, a nation such as China would reach its zenith and simply stay there, its technology and society maintaining the current level for probably a thousand years. We are doomed simply by the fact of who we are to be constantly looking for the next horizon, wherever it may be. It is for this reason that our societies have often broken tradition, and although this rarely happens with ease, it happens more easily for us than probably any other. Within us there is some sense that the old ways cannot always bear us hence, and that isn’t just childhood liberal indoctrination but often innate, ruthless Western pragmatism.

In the West, traditionalist movements have often lost out to progressive ones. This is self-evident. We rarely ever have successful movements that argue for the wholesale reinstatement of old values and old systems. Whether the Bourbon Restoration or the English Civil War, some concession is made to the loser, and the old way never truly comes back. Many in our times take the redpill and immediately begin looking back in history for solutions to our ills, whether it’s reevaluating the World Wars and their ideological battlegrounds, or poring over the history of the late Roman republic to see which modern-day figure corresponds to Caesar, who is Crassus or Pompey, what role Cicero would play today, whomever else may have been our Cincinnatus, and so on.

In the West, traditionalist movements have often lost out to progressive ones. This is self-evident. We rarely ever have successful movements that argue for the wholesale reinstatement of old values and old systems. Whether the Bourbon Restoration or the English Civil War, some concession is made to the loser, and the old way never truly comes back. Many in our times take the redpill and immediately begin looking back in history for solutions to our ills, whether it’s reevaluating the World Wars and their ideological battlegrounds, or poring over the history of the late Roman republic to see which modern-day figure corresponds to Caesar, who is Crassus or Pompey, what role Cicero would play today, whomever else may have been our Cincinnatus, and so on.

We risk worshiping history as an omnipotent guide, rather than a collection of principles and their consequences. By binding ourselves to an anachronistic way of life, however principally correct it may be or have been contemporaneously, we preclude ourselves from proactive measures in the present. If tradition is “not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire” then we must consider that said fire is not intended to be our funeral pyre, but a light into the darkness of times to come. To that end, we must act in the present, on the problems of the present, with solutions that are novel and particular to our time. In a way, this form of progressivism is traditional for the Westerner.

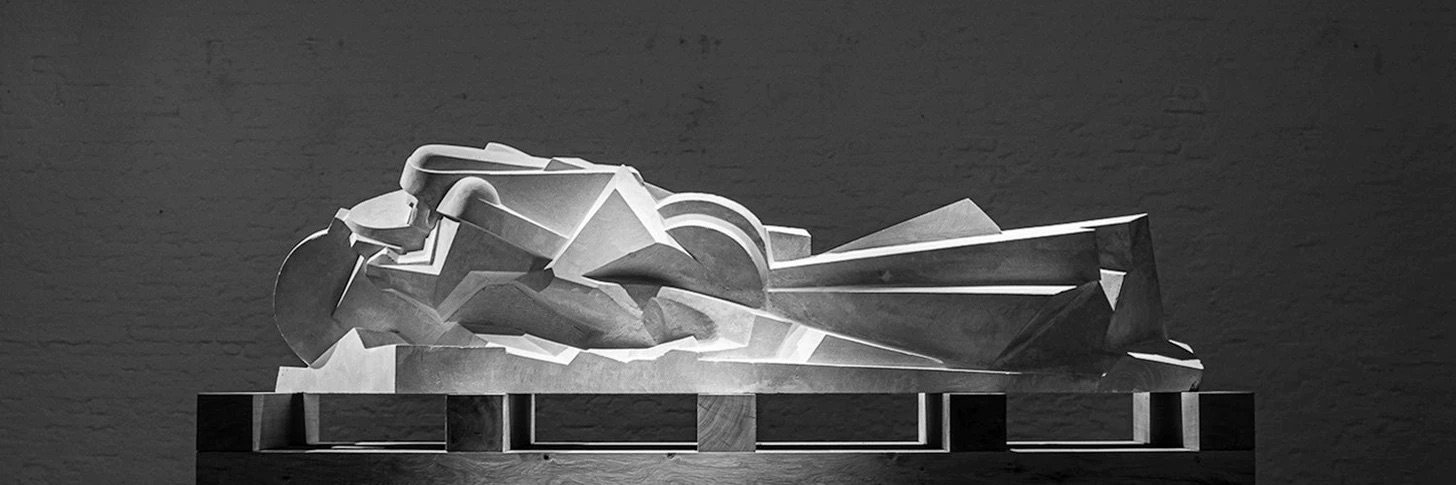

Many of the 20th century movements that are idolised by the newly-redpilled were, at the time, extremely progressive. Italian fascism was accompanied by a modernist art movement called futurism (beautifully expressed in the sculpture above by Fen de Villiers), and Mussolini himself started out as an avowed socialist, a very new movement at the time. Their political system, although nominally respecting the old monarchy of united Italy, superseded it in every way and was focused on developing a fresh, vibrant home culture and expansive empire. It did not confine itself to the artistic glory of the Renaissance, nor the conservative territories of the Kingdom of Italy. Everything was up for the taking, so long as it was deemed healthy for the Italian people and in favour of the fascist state. It was intended to be a beacon of modernism.

In Germany, Hitler was famously dismissive of the former Kaiser, and had no interest in reinstating him as monarch, seeing him as a stodgy figment of the past. National socialism was at the time a revolutionary movement, which delivered policies unheard of even in liberal Western countries – anti-smoking and pro-fitness campaigns, expansive women’s rights, animal rights and environmental protections, vast autobahn networks, state-sponsored family holidays (please read about Kraft durch Freude for a lesson in just how unorthodox NSDAP social policy was), and of course new artistic and architectural movements. It was roughly equivalent to a bunch of guys taking over the Greens party and turning all its goals away from suicidal liberal nihilism and towards the healthy furthering of Western people in balance with nature (what a great idea, but let’s leave that for another time). Both fascism and national socialism are seen by liberals today as repressive, reactionary regimes, perhaps because they feel liberalism alone should have a monopoly on the future! But there was a time when Westerners would look to problems in the present and attempt to overcome them in new ways. These visions, although progressive, were not by necessity liberal or degenerate.

We do face problems eerily similar to those found in the past. It is all too easy to think that Weimar problems require 1933 solutions. It is undeniable that our times are decadent and depressed, a terrible combination for the soul of any nation. However, the solutions presented by such systems are out of date by 100 years now, and the geopolitical factors that motivated them simply do not exist, although the outward appearance of them remains. Nobody alive today remembers an Imperial Western world. Our age of decadence was not immediately preceded by a golden age of innovation and expansion, rather it is a response to decades of undermining and subversion. Our nations are not homogeneously populated by a great swathe of upright, strong people. Weak men create hard times? Hard times last a lot longer than you might think, and a lot of the figures who believe they are reversing the trend of men being weak really have no idea what they’re up against. It’s about to get a lot harder. There’s no ready answer we can pull from history on this one.

Healthy progressive movements often run with new aesthetic visions. When the forms of the past no longer adequately express the world around us, we seek out a new understanding from the most sensitive among us. Once it is expressed in a pure way, a new school is founded on it, and we gain firm ground to build the future on. What aesthetic could sum up the spirit of our time? I am no artist, but I feel in our world a sense of loss, longing, and betrayal that wells up into a fountain of blood and revenge. I feel a great darkness hanging over the soul of Western man, a directionless rage simmering. Slowly we all come to see the many doors of possible recourse and redress closing to us, and before we say it, we feel it and we know: The longsuffering goodwill of the Western man is at its end.

Healthy progressive movements often run with new aesthetic visions. When the forms of the past no longer adequately express the world around us, we seek out a new understanding from the most sensitive among us. Once it is expressed in a pure way, a new school is founded on it, and we gain firm ground to build the future on. What aesthetic could sum up the spirit of our time? I am no artist, but I feel in our world a sense of loss, longing, and betrayal that wells up into a fountain of blood and revenge. I feel a great darkness hanging over the soul of Western man, a directionless rage simmering. Slowly we all come to see the many doors of possible recourse and redress closing to us, and before we say it, we feel it and we know: The longsuffering goodwill of the Western man is at its end.

Originally published at Mike Rusade’s Micro Crusade.