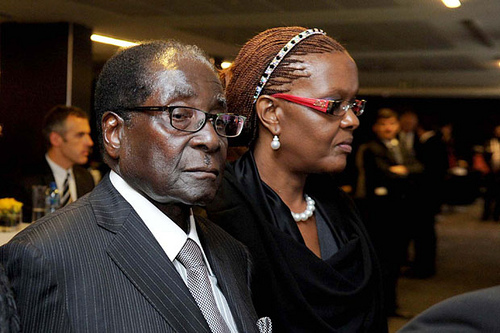

With the fall of Zimbabwe despot Robert Mugabe, late last year, John Elsegood reflects on the impact of that regime in the beautiful town of Mutare, after he arrived there in 1986 following a disturbing church invasion in that beautiful city.

The demise of Robert Mugabe’s gangster rule, after 37 years, is no guarantee of any improvement for that country, once considered the jewel in Africa’s crown.

An incident in Mutare (formerly Umtali in Rhodesian days), a delightful eastern highlands city of Zimbabwe, during a stay in 1986, epitomised the excesses of the regime’s long misrule and the area’s dramatic history.

During the last days of Ian Smith’s government in the Bush War of 1972-80 the beautiful tree-lined streets of Umtali came under mortar and rocket fire , from the adjoining heights, of neighbouring, and Marxist, Mozambique.

With majority rule in 1980 came a temporary peace for the 70,000 people of this city.

However peace in Mugabe’s state was always illusory for both black and white citizens and seeing the impact on a community of the gangsterism of his ruling party, ZANU-PF, was educational, to say the least.

On February 16th of that year, a 500 strong mob descended on St John’s Anglican Cathedral, and other church premises, assaulted parishioners and priests while the police looked on.

The spiritual heirs of the mob that once supported Barabbas, 2000 years ago, were there at the behest of the local strong man, Edgar Tekere (1937-2011), the local chairman of the party in Manicaland.

This historical cameo gives ample proof of the breakdown in the rule of law of a beautiful country.

Tekere was a cabinet minister in the early days of the Mugabe Government and no stranger to controversy. Charged with the murder of a white farmer, Gerald Adams, he was controversially acquitted and although sacked from the cabinet continued on as political power broker.

On the day he organised his rent-a-mob he arrived at the Cathedral and entered. Invited to attend the service and restrain the chanting mob he declined on both counts. In fact he went outside and invited the mob to take over. They did.

Pews were over turned, two priests assaulted-one being dragged down the full length of the church on his face, children thrown around and an old lady severely buffeted and carried out in shock.

The mob then danced on the altar and drank 16 bottles of altar wine. The Dean, John Knight and 20 parishioners stayed behind to see what the mob wanted. No clear picture emerged except false stories told to the squatters at St Augustine’s Mission that the Bishop wanted the land they were on for his own for his own (non-existent) cattle.

The police declined to intervene because it was “Tekere business” and “orders from above.”

The Asst Commissioner advised Dean Knight to move leave his home as Tekere had ordered an invasion of it.

Later the same afternoon two church members were captured outside the church’s office and assaulted by Tekere while held by his henchman. Police watched as those two victims were hurled into a car and taken away.

The bishop’s house was over run and stayed that way. When, after four days passed, a female SPCA inspector went to feed the dogs and chickens, she was forcibly evicted before being able to tend to the animals.

Mob rule ended on March 2 when the police were granted permission to move in against the thugs.

The matter did not end there, On Sunday, March 16, 1986, Dean Knight was contacted by a high ranking member of the politbureau, Didymus Mutasa, Speaker of the House of Assembly.

Mutasa informed the cleric that he had been responsible for critical international exposure the country had received on the BBC.

Accordingly, the Dean no longer felt safe in his own home and again vacated it and went into hiding. He was incommunicado during my visit and there were many fearful parishioners.

The background, to this madness in Mutare, centred over a dispute relating to control over St Augustine’s Mission School and its rebel headmaster, and Anglican priest, Keble Prosser.

Prosser belonged to the Community of the Resurrection, a British missionary organisation active in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe for, at that stage, 80 years. In September 1983, the mission pulled out and control of the school was handed back to the Diocese of Manicaland.

Prosser was recalled but did not go back as expected. As a ZANU-PF supporter during the Bush War he had local village support and also from Tekere.

When the diocese appointed an African headmaster, the lorry containing the new principal’s goods was turned back by the mob.

Mugabe, (then PM), sent a letter in January 1984, instructed Bishop Elijah Masuko and his school governors, to retain Prosser.

Prosser in the middle of the year then chose a new board without reference to the diocese. This comprised of local villagers, despite the fact that only five per cent of the pupils were locals, as the school was a national institution.

The compromise reached left the school with two boards of governors, including one of the country’s leading witchdoctors – a novel touch for a Christian school!

Apart from some commentary on the BBC there was a near deafening silence from the local, national and international media.

At the time the Deputy PM, Simon Muzenda, said the police had done their job lawfully and fairly and that they could hardly take sides in a purely administrative wrangle of the Church.

A pity the sorry cabal of criminal cranks that constituted Mugabe’s ministry didn’t heed the grandiloquent words of one of their ministerial colleagues, Herbert Ushewokunze (once under parliamentary investigation,and attack, for railway property fraud), who told a Police Seminar (2/11/82), grandiloquently:

“The police must respect liberty and the freedom to exercise one’s rights without hindrance provided the rights of other people are not invaded. The police have the paramount ethical and legal duty to ensure that law enforcement is carried out impartially and equally without regard for social standing, race or class. There should be no favouritism towards those of influence (be it political, social or economic) and neglecting the less able and less influential.”

The Mugabe regime, both in the relatively forgotten case relating to the mayhem in Mutare, and on so many larger issues, remains the antithesis of those words throughout the long era of corrupt misrule.

This article was originally published at Something Else with John Elsegood.

Photo by GovernmentZA