Why should you care about the Spanish Civil War?

Short answer? Because somewhere out there, there’s a little rich kid arts student with a black mask in his wardrobe who wants to smash your head in with an iron bar, and he still thinks he’s fighting it.

If you’ve been paying attention to the extreme left, you may have noticed their preoccupation with the events of 1930s Spain. Especially amongst the black-clad Anarchist thugs both here in Australia and around the world, the symbols and slogans of the conflict are still regularly used in the weirdest of contexts.

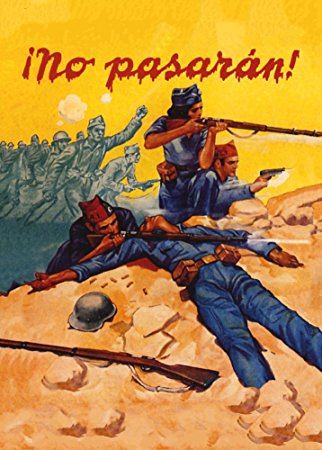

A few months ago, the Israeli-Australian provocateur Avi Yemeni was protested against by a crowd of Anarchists and Communists waving the flag of the International Brigades and chanting, “¡No Pasarán!” – the slogan of the failed Communist defenders of the Siege of Madrid.

For a variety of reasons, the extreme left seems culturally and mentally trapped in 1937, perpetually fighting a war that their side lost. In leftist mythology, the conflict has taken on a symbolic significance well beyond what it deserves. As the crimes and corpses of the Soviet Union and later Mao’s China began to stack up, and the true horror of the “worker’s revolutions” around the globe began to become undeniable to even the most fervent true-believer, the Civil War in Spain has taken on an almost iconic status.

Much like the modern leftist reverence for Chilean Communist leader Salvador Allende, Spain became special because in the eyes of leftists the “good” side lost. This allows the left to imagine how wonderful it would have been if they had won without dealing with the messy realities that inevitably popped up whenever they did.

In the mind of modern leftists, the Communists and Anarchists of that conflict are pure, unadulterated heroes fighting a doomed and noble struggle against an evil fascist/capitalist/military/monarchist conspiracy to overthrow a democratically elected leftist government. As usual when it comes to leftist fantasies, the actual situation was slightly more complex.

After World War I, it seemed as though Communism was the coming wave of the future. The Revolution in Russia had inspired copycat movements all over Europe. A flurry of short-lived revolutions took power in parts of Germany. Bela Kun and his murderous thugs had a brief reign of terror in Hungary. Communists precipitated a seldom heard about yet impressively bloody civil war in Finland. In Italy the “two red years” saw Marxists and Anarchists try and take over the country, only to inspire a backlash that led to Mussolini. Even sleepy Holland managed to have an aborted Marxist coup during the period of “De Roode Week” (the Red Week).

While these revolts failed, the left-leaning intelligentsia and the increasingly extremist union movements across the continent genuinely believed that the revolution in Russia had brought a bright shining new future and that its spread across the remainder of the world was only a matter of time.

Across the West, observers seemed to be waiting with bated breath to see where the next spark that would engulf the world would be lit. As the roaring ’20s turned into the Great Depression ’30s, the progress towards a Communist future seemed even more inescapable. The only question seemed to be where the new era would begin. Many educated people believed Germany would be the first to rise in revolution. After Hitler scuttled that option, most assumed that either an increasingly unstable France or even Britain would be the first western country where “the workers” would take control. Nobody thought it would be Spain.

By the time the second republic was formed in 1931, Spain had been suffering through a bad couple of centuries. The once-mighty superpower of Europe had lost its colonies, lost its gold and had an economy that was backward and stagnating even before the onset of the Great Depression. Spain had wisely stayed out of the First World War, but the once-mighty nation had been rocked by domestic leftist agitation in Catalonia and a seemingly never-ending war in Morocco.

As a last gasp, the highly unpopular King Alfonso XIII backed a military coup in 1923 that brought Miguel Primo de Rivera, a highly eccentric aristocrat, to power. While he wasn’t the worst leader, Primo de Rivera certainly didn’t solve any of the underlying problems of Spain, and was forced to step down in 1930, taking the last of the King’s credibility with him.

The Left wins power

So an abdication happened, a republic was proclaimed, and in a reasonably fair election a Centre-left coalition was elected. The new government attempted to assist the rural poor of Spain by instituting an eight-hour day and giving tenure to farm workers. They also drafted a new constitution that banned religious groups from being involved in education and began moves towards the confiscation of church property by the state. This was accompanied by a wave of anti-Catholic violence and church burnings by Communists and Anarchists who bitterly hated Christianity and thought that the march towards revolution was moving too slowly for their tastes.

Exiled King Alfonso was tried in absentia and condemned to life imprisonment as the Government lost the support of centrist parties and started sliding ever further to the left. Prime Minister Manuel Azaña pushed more moderate republican forces aside, and with the support of the Socialists, came to power in late 1931. One of his first actions was to declare that Spain had “ceased to be Catholic”. The new rulers changed the flag, the anthem and the symbols of Spain. All old things were to be destroyed, all new things to be exalted.

Azaña reduced the size of the Spanish Army and purged some of the more outspoken monarchist officers; he also abolished Church-operated charities. The Spanish legislature, the Cortes, enacted an agrarian reform program, under which large private landholdings (latifundia) were confiscated and distributed among the rural poor.

This wasn’t enough for the Socialists and nowhere near enough for the Anarchists. They wanted the destruction of religion, the abolition of private property and the creation of collective farms, and they wanted these things right away.

The anti-clerical extremism of some of its factions and the failure of leftist policies to fix the economic situation eventually tore the first government apart. Another election was called for 1933. The voters were disillusioned with the left and overwhelmingly voted a coalition of centre-right wing and conservative parties into power.

The Right wins power

And that’s when all hell broke loose.

The Anarchists and Marxists had not expected that the left would ever lose an election. As far as they were concerned, the dark, evil conservative chains of the past had been broken and the people had been freed to embrace the new glowing dawn of socialism. They never expected that the people would vote against the wondrous march of progress.

Anyone who observed the leftist reaction to the Trump election or the Brexit victory can recognise the similarities. The far left in Spain was dumbstruck: how could the evil capitalists have fooled the workers and peasants into voting against their own interests? Surely the people understand that we know what is best for them? It must have been fraud! They must have cheated somehow!

When the centrist Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux invited three right-wing representatives into his cabinet, the left went nuts. All over the country Socialists and Communists declared a general strike in an attempt to overthrow the government.

In most places the revolt was put down quickly. Anarchists in Zaragoza held out for four days before the tanks of the Army crushed them, Catalonia unsuccessfully declared independence (sounds familiar), but in the heavily unionised mining towns of the mountainous northern Asturias region the militants held out.

In the Asturias, an impressive 30,000 workers were called up and armed by their socialist unions in less than ten days. They took over police barracks and marched in a column on the provincial capital of Oviedo. The miners took the Soviet Union as a model and set up town assemblies or ‘revolutionary committees’, to govern towns they controlled. Political opponents, businessmen and police were tortured and executed, while churches, convents and part of the university at Oviedo were destroyed.

In the coal-mining town of Turón, eight de la Salle Brothers were involved in an educational mission, living in a community there and teaching in a church school. The Brothers were known to defy the government ban on teaching religion and they openly escorted their students to Sunday Mass.

The Brothers’ school was an irritant to the Communists in charge of the town because of the religious influence it exerted on the young. On Friday 5 October they forced their way into the school and arrested both the Brothers and a Passionist priest who was visiting to hear their confessions. Over the next few days they were tortured, tried by a revolutionary court and sentenced to death. On 9 October 1934, in the early hours of the morning, they were shot and buried in a common grave.

The generally conservative and often deeply Catholic officers of the Spanish Army were not amused. One of them in particular, a younger general and a veteran of the Moroccan war named Francisco Franco, was placed in informal command of the operation to put down the rebellion.

Franco described the miners’ revolt as “a frontier war, and its fronts are socialism, communism and whatever attacks civilisation in order to replace it with barbarism.” He sent in hardened veteran troops from Africa, Spanish Foreign Legionnaires and even columns of the bloodthirsty Muslim Moroccan auxiliaries known as “Regulares”.

The fighting did not last long. The government troops were not gentle. Around 3000 miners were killed and 30,000 taken prisoner. The crackdown was harsh and the troops under Franco showed no mercy. There were reports of looting, summary executions, torture and even the tacit unleashing of the Muslim Moroccan troops to rape leftist women. In the eyes of Franco, and of other officers involved such as the very right-wing Juan Yagüe and the formerly left-wing Eduardo López Ochoa, the Communist rebels had behaved as less than animals and so would be treated as such.

It’s probably fair to say that this event did not do much to cool down the political tensions in the country.

Spain had entered the period known as the “two black years”. The far left, stymied in their attempts at revolution, turned to street violence. Official statistics state that in this period 330 people were assassinated in addition to 213 failed attempts, and 1,511 people wounded in political violence overwhelmingly committed by the left. Those figures also indicate a total of 113 general strikes called and 160 churches, convents and monasteries burned.

The centrist republicans under Lerroux were rocked both by the increasing chaos and by a series of corruption scandals. The left was getting more and more extreme in their demands, and the right was beginning to organise to defend themselves against the ever-increasing leftist violence. The centrists began to look ever more like corrupt con-men without the passion of their opponents on either side, and their government fell apart. New elections were called in early 1936, which the increasingly radical and better-organised left won handily.

The Left wins power again

The centre left and centre right had faded into nothingness. Everyone was drifting towards the extremes. Manuel Azaña attempted to form another Government but was blocked by the extremist Socialist leader Largo Caballero. Caballero, a fierce and charismatic man, had moved his party closer to the Communists, and by extension Moscow. Socialists took to the street in mobs to break into prisons and free those who had been involved in the Asturias rebellion.

The army and the police forces (especially the urban-based elite Assault Guards) were purged as much as possible of “political undesirables”. Franco was too influential to get rid of and so was sent out to the Canary Islands in a kind of exile.

Positions inside the Socialist party began to be filled by doctrinaire Soviet-line Communists with Largo Caballero’s blessing. Largo preached publicly of the inevitable revolution that he believed was imminent and that would lead Spain into a bright new future of equality as it had in Russia. Trotsky, writing from exile himself, agreed. Most on the left worldwide, as well as here in Australia, believed that the Soviet Union was on the right side of history, and that Spain and all other nations would eventually and inexorably wind up at that destination. It was only a matter of time.

After their failure in the election, the centre-right parties lost tens of thousands of members, especially amongst younger men, to the previously inconsequential far-right Falange movement. The blue-shirted toughs may have had their flaws, but in the eyes of an increasingly alarmed populace, they were seen as at least being willing to fight back against the Communists in the streets.

The far left was not going to allow another election victory by the right to derail their “progress”; they had learned their lesson. All over Spain, leftist police and military officers began training and arming Socialist militias for the inevitable revolution. One such man was the Assault Guards officer José Castillo.

José Castillo was a former military man and veteran who had been selected by the government as an Assault Guards officer because of his reliably leftist politics. His affiliations were no secret; he was a member of the “Republican Antifascist Military Union” and in his spare time trained Socialist Youth Militia groups in military skills and tactics in preparation for the revolution to come.

In April 1936, he commanded the Assault Guard unit which attacked right-wing mourners at the funeral of a policeman murdered by Communists. Unsurprisingly, this did not make him extremely popular in right-wing circles. He and his wife began to receive death threats in the mail. On the evening of 12 July, Castillo left his home in central Madrid to go to work. On the pavement outside he was killed by four unidentified men with revolvers.

Early next morning a group of socialist militiamen, Assault guards, leftist police and even a bodyguard of Socialist Party leader Indalecio Prieto pulled up in trucks in front of the house of Monarchist politician José Calvo Sotelo, the man who had now become the main opposition leader of the right in the wake of their 1936 electoral drubbing. They informed the elected Member of Parliament that he was under arrest. Sotelo kissed his wife goodbye and went with them.

As a deputy in the Cortes, Sotelo had constitutional immunity from arrest, so he must have known what was coming. He must have known that although they had no right to arrest him, if he had not gotten into the truck the leftists would have murdered him in front of his family. He bravely stepped in the truck knowing he would not be stepping out, and he didn’t.

Sotelo was shot in the back of the head as he rode in the truck by Luis Cuenca, the bodyguard of the president of the Socialist Party. His body was dumped outside a graveyard and his murderer went directly to the offices of the Socialist Party Newspaper El Socialista to boast about what he had done.

The government launched an inquiry that found no-one at fault. Despite everyone knowing the names of the murderers and that they were nearly all serving Assault Guards, no charges were ever laid. As Sotelo was buried, fighting between the leftist Assault Guards and blue-shirted Falangists broke out in the streets surrounding the cemetery of Madrid, resulting in four deaths.

For conservatives, this was the last straw. The Communists and Anarchists had been burning cathedrals, killing priests and monks, murdering and torturing anyone who stood in their way and stealing the property of anyone who didn’t. The “mainstream” leftists were now seemingly willing to put these thugs in uniform and let them kidnap and assassinate members of parliament they disagreed with. They couldn’t even bury their dead in peace.

There were many generals in the military that had been planning for this moment. Like Franco, they had been sidelined or demoted by the republican government. Like many of the devout, they had been appalled at the desecrations of religious sites and the murder of clergy. Personally, they were outraged at the deliberate shrinking of the Army in what looked like a planned strategy to make them too weak to resist a Bolshevik-style coup. Now finally they had the furious support of mainstream conservative public opinion and saw their chance.

Both José Castillo and José Calvo Sotelo were buried on July 14. Three days later on July 17, the main body of the army rose up in Morocco and declared a coup.

The War begins

The Civil War had begun.

All over Spain, the Army marched out of their barracks and attempted to take control. In every large city and in wide swaths of the countryside they were beaten back by well-armed and well organised Marxist and Anarchist militias, joyfully proclaiming that the time of the revolution had arrived.

The centre left was swept aside as the far-left took the driver’s seat. All over the countryside the Red Terror reigned. Before it was over, up to 170,000 people would be killed. This number included 6800 members of the clergy. Overall, 13% of the priests and 23% of the monks in Spain, as well as 283 nuns, were killed, many of the last being badly tortured.

The stories are horrific.

The parish priest of Navalmoral was put through a parody of Christ’s Crucifixion. At the end of his suffering the militiamen debated whether actually to crucify him or just shoot him. They decided on shooting.

The Bishop of Jaén Manuel Basulto y Jiménez and his sister were murdered in front of two thousand cheering and celebrating socialists by a special executioner, a woman nicknamed La Pecosa, the freckled one.

The priest of Ciempozuelos was thrown into a corral with fighting bulls, where he was gored into unconsciousness. Afterwards one of his ears was cut off to imitate the feat of a matador after a successful bullfight.

In Ciudad Real, a priest was castrated and his sexual organs stuffed in his mouth. Clergy were forced to swallow rosary beads or were thrown down mine shafts. Priests were forced to dig their own graves before being buried alive.

On the night of 19 July 1936 alone, fifty churches were burned. In Barcelona, out of the fifty-eight churches, only the famous Sagrada Familia Cathedral was spared, and similar events occurred almost everywhere in Republican Spain.

The religious of Spain, including many generals, had been outraged by the murder of eight monks in the Asturias. One could probably assume they were a little bit more upset than that now.

With the help of Germany and Italy, the Nationalists managed to land the battle-hardened army of Africa on the Spanish mainland. Regular versus irregular warfare is usually easy to bet on and this was no exception. In the first few months after the landing, the reds were uniformly beaten back.

They fled like rats, leaving the smoking remains of the churches they had burnt and the bodies of decent citizens they had murdered behind as the true army of Spain advanced.

The Nationalists were not in a mood to be merciful. The White Terror eventually killed even more than the Red Terror had.

Overall, the war led to the deaths of 600,000 people, the majority of which were executed or murdered outside of combat. The left had believed that their violent revolution was inevitable for so long they hadn’t really thought about what would happen if the right fought back. While the terror carried out by the reds was the work of disorganised fanatics, the responding terror from the Nationalist side was very organised and methodical indeed.

Why we should care today

The history of Spain, as well as our current age, teaches us one important thing: the extreme left never stops; it never slows down and never relents. It pushes forward with all the fanaticism of a true believer who sees paradise perpetually behind the next hill of corpses. Nothing is sacred, no victory is ever enough. We see in Australia today that ideas that even leftists scoffed at a decade ago are now dogma morally defensible by mob violence.

There will never be a successful compromise, never a time when they will say, “OK, we’re happy now.” Unless the sane in society push back against them, fight the implementation of their mad fever dreams and flush them out of society like the toxins that they are, then civil war or societal collapse is sooner or later the inevitable outcome.

Because they won’t stop. They were getting what they wanted in Spain but over-reached because it wasn’t fast enough. They weren’t content to let the conservatives slowly get used to whatever changes they were implementing, everything was too slow, and even anyone on the left who objected to their violence was suspected as a traitor. Eventually their murderous impatience drove the middle ground into the arms of the generals, many of whom were only too willing to ride the tide of public opinion. The far-left in our country feels like it can beat people in the street for disagreeing with them, and for the most part the more mainstream leftist establishment agrees. Our top university even prints how-to books promoting leftist terrorist groups. How long until they feel safe committing murder?

The leftists doing violence on our streets and teaching in our schools follow the same ideologies and carry the same flags as those who carried out the Spanish Red terror. They hold up those murderous totalitarians as heroes. The lesson from history is that it is better to confront them now, to drag them squealing out into the disinfecting sunshine and show the public what they are up to, than to have to fight them later.

Civil wars are not nice. Anyone who has visited the poignant Valley of the Fallen in Spain can tell you that massive monument to the dead of the war is not a place of celebration but of commemoration and sorrow. If the extreme left is not fought now, they will eventually drive us over the cliff edge and down into the abyss.

After all, they’re on the right side of history. It’s just inevitable.

Photo by Catedrales e Iglesias