This article was published in January 2015 at www.rodlampard.com shortly after the Islamic terrorist attack against the office of Charlie Hebdo magazine.

Reading C.S Lewis’ essay, ‘Blimpophobia, 1944’, resulted in me sifting through the 1956 autobiography of satirist David Low.

Reading C.S Lewis’ essay, ‘Blimpophobia, 1944’, resulted in me sifting through the 1956 autobiography of satirist David Low.

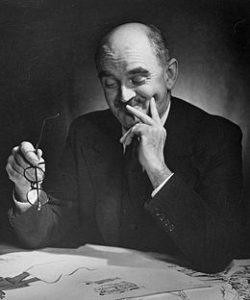

Low was born in New Zealand, later moving to Britain, where he became an influential newspaper cartoonist.

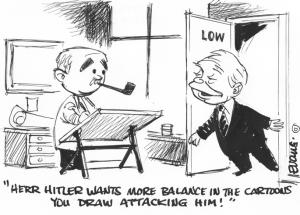

The following quote is a reflection he gives on a cartoon which he drew that featured Mohammed, among others.

Based on the reference to Cricketer, Jack Hobbs, in the text, the date these events took place is 1925.

It’s worth pointing out, then, that this is 90 years old. Given the recent events, I consider its sharp relevance to be poignant and of significant importance to current debates.

With such primary information it is harder for ‘strategies of evasion’[i] to be employed by an esoteric anti-Americanism hell-bent on pushing denial in a blame game that seeks to disempower opposition and further advance the lordship of an overbearing ideological agenda. This point is identified by Jean Bethke Elshtain’s analysis of responses to her attempts to reasonably engage with Muslims and the Western-Left about the harder questions, such as: whether or not there is an embedded relationship between Islamic terrorism and genuine Islam.

Low’s generalisations aside (since not all Muslims would have been in an outrage about it at the time), his experience almost perfectly parallels recent events. It is not something easily overlooked.

Although I get that Low is lamenting a poor decision, I’m not completely sympathetic with him at the end. This is because there are negative ramifications against freedom of speech brought about by these arbitrary responses.

‘Jack Hobbs, the famous cricketer, had touched a high point in his career in equalling Grace’s batting record. I celebrated the event in a cartoon entitled ‘Relative Importance’ depicting Hobbs as one of a row of statues of mixed celebrities, in which his towering figure overshadowed Adam, Julius Caesar, Charlie Chaplin, Mohammed, Columbus and Lloyd George.

It was a piece of mere facetiousness, meaning nothing, but since the public interest in Hobbs was strong the Star gave it an importance it did not deserve by printing it twice the usual size.

It brought a large number of letters, eulogizing and applauding, which surprised me, and an indignantly worded protest which surprised me even more from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Mission, which deeply resented Mohammed being represented as competing with Hobbs, even of his being represented at all.

The editor expressed his regrets at the unintentional offence and regarded the whole thing as settled.

Two weeks later cables from India described a movement in Calcutta ‘exhorting Muslims to press for resolutions of protest against the Hobbs cartoon which shows a prophet among lesser celebrities. Meetings will be held in mosques.’

An additional complication arose. Not only one prophet but two had been profaned because Muslims reverence Adam also.

Bitterness and fury were redoubled.

To quote a Calcutta correspondent of the Morning Post:

“The cartoon has committed a serious offence, which had it taken place in this country, would almost have led to bloodshed. What was obviously intended as a harmless joke has convulsed many Muslims to speechless rage…An Urdu poster has been widely circulated throughout the city, calling upon Muslims to give unmistakable proof of their love of Islam by asking the Government of India to compel the British Government to submit the editor of the newspaper in question to such an ear-twisting that it may be an object-lesson to other newspapers. The posters have resulted in meetings, resolutions and prayers.”

The British Government was unresponsive, for we heard no more.

It is not without a twinge of regret that I reflect upon the loss to history of a picturesque scene on Tower Hill, with plenty of troops, policemen and drums, on the occasion of my unfortunate editor having his ears twisted on my behalf.

When I was talking with Mahatma Gandhi some years later, he deplored the insufficient number of cartoonists in his country and suggested that the well-known appreciation of satire possessed by Indians might make it a congenial place for me to spend some time professionally.

I refrained from comment.

The whole incident showed me how easily a thoughtless cartoonist can get into trouble. I had never thought seriously about Mohammed. How foolish of me. I was ashamed – not of drawing Mohammed in a cartoon, but of drawing him in a silly cartoon.’[ii]

Lewis used Low’s cartoon of the infamous Colonel Blimp as a critique of both over-enthusiastic nationalism and hyper-moralist pacifism.

It’s probably not all that detached from relevance to conclude with his indictment against having a permanent home-guard and the invitation to disaster that total disarmament would bring:

‘My present purpose is not to settle a question of justice, but to draw attention to a danger.

We know from the experience of the last twenty years {1924-1944} that a terrified and angry pacifism is one of the roads that lead to war.

I am pointing out that hatred of those to whom war gives power over us is one of the roads to terrified and angry pacifism…

A nation convulsed with Blimpophobia will refuse to take necessary precautions and will therefore encourage her enemies to attack her’[iii]

This article was originally published at http://www.rodlampard.com/

Sources:

[i] Elshtain, J.B. 2008 Just War Against Terror, Basic Books, Kindle Ed.

[ii] Low, D. 1956, Low’s Autobiography, Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp.123-124

[iii] Lewis, C.S. 1944 Blimpophobia in Walmsley, L. (Ed.) 2000, C.S.Lewis Essay Collection Harper Collins Publishers

Image: David Low (Wikipedia)