Originally published at Occidental Observer.

Jason Cannon

I suppose, after me, all the shits came in? — Phillip Roth

Australia was one of the last holdouts in the West in policing and restricting the publication, importation, and distribution of pornography and other forms of obscenity. Where censorship regimes in the USA and UK had already collapsed by the mid-1960s, as late as the year 1971 vice squads in police forces around Australia still ran raids of bookstores believed to be selling obscene literature. Political leaders of the era such as the formidable Vice-Premier of the state of Victoria, Sir Arthur Rylah, and his counterpart in the state of New South Wales, Sir Eric Willis, still possessed the vocabulary and conviction to resist the mass sexualisation of society and provide a defence to the Christian morals of the Australian people. The prohibition of obscene publications is now a politically dead issue, but opposition to it, the anti-censorship cause as it was known, once occupied an incredibly important front in the wider cultural and sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s that set countries like Australia onto a path of cultural and demographic ruination. Every country in the West has an infamous piece of literature or film that either put a foot in the door for the entrance of pornography or otherwise resulted in the breakdown of obscenity laws and controls in their respective countries, often as a result of a much-publicised legal trial. In the United Kingdom, this was works such as Lady Chatterley’s Lover (first unexpurgated version in the UK in 1960) and Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964). In the United States, the film The Pawnbroker (1964) saw the end of the power of the Motion Picture Production Code, a set of industry guidelines on content that was imposed on the film studios of Hollywood. But in Australia, this ignominious title is given to Philip Roth’s most famous work, a now iconic Jewish book by the name of Portnoy’s Complaint (1969).

As this essay will uncover, the story of the end of obscenity law and censorship controls in Australia—events that subsequently caused the flowering of the sexual revolution—is one of a cultural and political push teeming with Jews. Although not intended to do so, the recently released book The Trials of Portnoy [1] by Australian journalist Patrick Mullins exposes the key Jewish role in this undertaking, showing the deeply involved nature of Jewish ideas, activism, and money, and how crucial Jewish literature was in breaking down the laws that served as a bulwark against the advance of the sexual revolution and the permissive society. Throughout the book, Mullins identifies the major pre-Portnoy victories for anti-censorship that led up to the decisive final battle over Portnoy’s Complaint. Each subsequent victory served to embolden the anti-censorship cause and its supporters, who were convinced the march of progress was on their side, and conversely weaken, embarrass, and enrage the defenders of sexual mores and the moral virtues of Australian society. At the conclusion of this came Portnoy’s Complaint, which was prosecuted for obscenity in courtrooms around the country in the most widely publicized and debated censorship trials since World War II. After Portnoy, it was no longer possible for an obscene publication to be banned in Australia.

Legal Framework

These events will be explored in turn, but a brief digression is necessary to understand the structural basis of the obscenity laws and other legal restrictions that operated throughout the country. In the pre-internet era, the Australian legal framework for the restriction and prohibition of publications deemed to be obscene was contained in federal law jointly under the Customs Act and the Post & Telegraph Act, which took their inspiration from the UK Obscene Publications Act of 1857. Together these Acts gave broad powers to the Federal Customs Minister and customs officials to proscribe “blasphemous, indecent or obscene works” onto a banned publications list and restrict the importation and local distribution of such banned works. This included the power to search through the luggage of arriving travellers from overseas. Further state laws existed, with some variations on a state-by-state basis, to police obscenity on a local level. These were the laws utilised to, for example, fine a bookstore caught selling obscene literature or people caught in possession of a federally prohibited import.

The legal definition of obscenity used in Australia was established under common law precedent by English case law in Regina v. Hicklin 1868, which entrenched what came to be known as the Hicklin Test of obscenity. Central to the Hicklin Test was the question of whether the publication under consideration had “the tendency to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.” As such, the focus of the Hicklin Test of obscenity rested not upon the impact of the publication on mature and law-abiding adults, who were considered morally upstanding enough to recognise the obscene work and handle it appropriately, but on those such as children, a group seen as particularly susceptible to the corruption of obscene literature due to their still-developing minds and therefore far more in need of strong laws to restrict its dispersal throughout society. The Hicklin Test did not require obscenity to be established in the context of the publication as a whole. Instead, a publication could be prohibited even if only a few passages in the entire text were found to be obscene. In the era before the sexual revolution, it was exceptionally rare for the law to confront the types of obvious pornography that are commonplace now. Instead, works deemed obscene were those of a sexually explicit or indecent nature, those exhibiting particularly graphic violence, or works that contained egregious attacks on religious beliefs.[2]

The Hicklin Test also implicitly acknowledged a fact that is ignored by pornographers and other liberal opponents of obscenity laws, namely that once an adult can legally and freely access something, it is then not difficult for it to fall into the hands of a child. Even if an age-restricted product can only be purchased in a store by an adult, from that point onwards, any control over its future readership or viewership is entirely down to the prerogative of the purchaser, or simply a matter of chance. No amount of age-restrictive laws on purchase or distribution could, nor can, stop a pornographic magazine/videotape or a violent video game from being discovered hidden under a bed by a child, or from being given by a careless 18-year-old to a younger sibling. Put simply, one cannot effectively protect children from pornography without also restricting it for adults.

The Hicklin Test was also introduced as the definition for obscenity in America in Rosen v. United States (1896), where a New York Jew by the name of Lew Rosen was found guilty of using the postal service to send an obscene publication. Hicklin was later overturned in the US in favour of a ‘community standards’ test (also known as the Roth test) in the landmark Supreme Court case Roth v. United States 1956, where yet another Jew, publisher Samuel Roth, was convicted for selling erotic literature.

OZ Magazine

Early rumblings of change came in 1963 with the founding of the magazine OZ, the premier satirical publication of the 1960s counterculture in Sydney. Established by three students at the University of Sydney, all of whom later went on to prominent positions in Australian cultural life, OZ grew out of the libertarian subculture of the “Sydney Push” and took its cue from Jewish satirists Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, the British magazine Private Eye, and the satirical BBC television program That Was the Week That Was. OZ sought to expand published counterculture in Sydney beyond the limited confines of the student press, prominently Honi Soit at the University of Sydney and Tharunka at the University of New South Wales, and established itself as a literary focal point for the growing forces of the New Left. Alongside its opposition to censorship, OZ was a trailblazer in Australia for a number of other political causes that would soon become major left-wing policies, from the anti-Vietnam War effort, to the dismantling of the White Australia Policy. The founders of OZ magazine, as well as the other leading members of this subculture (Wendy Bacon, the former editor of Tharunka, was another prominent anti-censorship activist) were deeply influenced and indebted to Jewish psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Reich. Reich’s works in particular formed the basis of much of their anti-censorship critique attributing sexual “repression”—including the proscription of sexually obscene literature—as a root cause of social, economic and political ills in society, as well as providing a seemingly scholarly basis for their belief in the abnormality of Christian morality.

Publication of the first issue of OZ in April 1963 met with immediate outcry. The magazine featured a series of interviews with an abortionist and young women who had procured abortions, as well as a tongue-in-cheek article about the history of chastity belts—intended as a metaphor for Australian sexual norms being “locked in the past.” The founders pled guilty to charges of obscenity levelled against them by the NSW government and were fined 20 Australian Pounds. Unrepentant, the founders of OZ were again charged and found guilty of obscenity for Edition 6 of the magazine in February 1964, and even harsher penalties were imposed, including a prison sentence. Wanting to take a stand against censorship, outraged by the severity of the charges and realizing that the magazine would not survive its infancy much further with repeated convictions, they lodged an appeal against the decision. The case was heard by the Jewish Appeals Court Justice Aaron Levine, a known progressive justice, who bucked public outrage by overturing the obscenity charges, ruling that OZ was satire and that the prosecution had failed to identify any real examples of people that would be corrupted or depraved by the publication, and had to point to more than “a theoretical group of unidentified persons”[3]—a stark redefinition of the Hicklin Test.

Levine’s progressive credentials would solidify in 1971 when he adjudicated in R. v. Wald[4], a case which effectively legalised abortion in the state of New South Wales. Justice Levine provided a defence to abortion on economic and mental health grounds so broad, that legislation to de-criminalize abortion was not taken up in NSW until nearly 50 years later in 2019. The founders of OZ later relocated to the UK, starting London OZ in 1967, and the cover pages of the magazine became progressively more pornographic and LSD-influenced, owing to use of that drug by the editors. The May 1970 edition, Schoolkids OZ, written by and aimed at high school teenagers, was the subject of one of the last major obscenity trials in the UK.

The Trial of Lady Chatterley

Infamous in the history of UK literary obscenity, the unexpurgated publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover had been banned in Australia since 1929 due to its erotic passages. The issue had lain dormant in the country until 1964, following the UK publication of The Trial of Lady Chatterley, an account of the famous court case four years earlier (R v. Penguin Books Pty Ltd) that broke UK obscenity laws. For including the offending passages, The Trial of Lady Chatterley was also subsequently banned in Australia. A rescue mission for The Trial would come in the form of a trio of liberators, who formulated a daring approach to flout Australia’s obscenity controls. This trio was led by Jewish entrepreneur and property developer Leon Fink, conspiring with Alex Sheppard, the Secretary of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties (CCL), and a local bookshop owner and tenant of one of Fink’s properties, to secretly publish a local edition of the book. With Fink bankrolling the illegal enterprise, a copyright was obtained from UK publisher Allen Lane, and Fink had torn up sections of the book sent to Australia through the post by friends overseas. Using the smuggled pages, 10,000 copies of the book were printed in secret, and distributed to select bookstores around the country in April of 1965.[5] Once the books were in place, Fink and Co. notified the Australian government of their act in an attempt to pressure them to rescind the ban. Prosecution of bookstores selling the book was attempted by Arthur Rylah in Victoria, but the stunt was an embarrassment to the federal government, who promptly gave in and removed Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the Trial of Lady Chatterley and a number of other works from the prohibited list.

The incident exposed the need for a uniform approach to obscenity across all states, as the anti-censorship activists were now getting bolder with their approach. Amendments were made to the Customs Act to tighten up procedure, to close the loophole for local editions of banned works, and a new Board of Review was established to act as a higher review authority than customs officials, which was given the ability to exempt from restriction works that were of “literary, artistic or scientific merit.”[6] This flimsy strengthening of obscenity law was utterly undone however with the landmark High Court of Australia case Crowe v. Graham (1968), an appeal against a conviction of obscenity in relation to two self-published magazines. Despite upholding the obscenity convictions, Justice Windeyer overturned the Hicklin Test in Australia, specifically citing Roth v United States in his decision, and formulated a new Australian test for obscenity based on the Roth Test: whether the publication would “offend the modesty of the average man or woman in sexual matters.”[7] The shift was subtle at the time, but it had far-reaching implications for the Portnoy’s Complaint battle that was soon to come. Thereafter, a publication declared obscene only had to answer for an offence against broad “community standards” (a community acknowledged to have a “new frankness regarding matters of sex”[8]) not against the category of “those whose minds are open to such immoral influences”—that is, primarily young people whose minds were still being formed. The two magazines in question, Censor and Obscenity, were amateurish publications, designed to do little more than thumb disapproval at obscenity laws, and contained a hodgepodge of pornographic images and selections from banned literature. Existing sources are unclear on the identity of the culprits, but they are likely to be more members of the same Reich-influenced university milieu as OZ and the university press; OZ advertised for both magazines within its own pages.

American Hurrah

A performance of the play American Hurrah at a Sydney theater became the scene of another victory for the anti-censorship cause, where a complaint from a local grandmother, who mistakenly attended the performance with her grandchild, led to threats of legal action from deputy leader of the State Government, Eric Willis. Her complaint was directed at a series of obscenities scrawled on the walls of the set during the third act of the play, a set piece intended by the playwright to shock the audience. Written by Jewish playwright Jean-Claude van Itallie, American Hurrah premiered in New York in 1966, directed by Jews Jacques Levy and Joseph Chaikin and critically explored the themes of consumerism and American involvement in the war in Vietnam. The play had gone largely unnoticed until the complaint, but the theater company agreed to remove the offending portions of the set from all performances henceforth. In response, a group of outraged intellectuals conspired to stage a free performance of the play with the offending set pieces included. Willis placed police into the audience, in order to shut down the free performance should they discover that the offending parts were included. The organizers, the “Friends of America Hurrah” which included Jews Cyril Pearl and Harry Seidler, watched on as the free performance degenerated into a pornographic spectacle:

“Two actors dressed as dolls simulated sex, wrecked the set, and drew on the walls the words fuck shit, and, a big cock up my juicy cunt. As police all over their theatre leapt to their feet, the actors jumped into the audience and made for the side doors.”[9]

Later performances of the play were restricted but the perceived heavy-handedness of Eric Willis’s approach was taking its toll. The anti-censorship cause won more converts, who felt that the mere presentation of “four-letter words” was no longer sufficient grounds for legal action.

Dennis Altman’s Suitcase

Justice Aaron Levine made another appearance in a legal case bought by Dennis Altman and the CCL in 1969, appealing the act of a customs official who seized two copies of banned literature from Altman’s luggage on a return trip from the USA—Sanford Friedman’s Totempole and Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckenridge. Altman saw the opportunity to try the strength of the revised Customs Act in the aftermath of the backdown on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and another prominent censorship case made its way before Justice Levine. Like the Jewish homosexual protagonist in the novel Totempole, Altman was also a Jewish homosexual, and would later become Australia’s foremost gay rights activist, soon to publish his iconic but now forgotten work Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation in 1971. Levine ruled that Totempole was not obscene and should be returned to Altman and upheld the ban on Vidal’s Myra Breckenridge, but as Levine was delivering his judgement, greater efforts to bring down Australian censorship laws were fermenting in Australia and abroad.

Portnoy’s Complaint

“What I’m saying, Doctor, is that I don’t seem to stick my dick up these girls, as much as I stick it up their backgrounds—as though through fucking I will discover America. Conquer America—maybe that’s more like it.” — Alexander Portnoy.

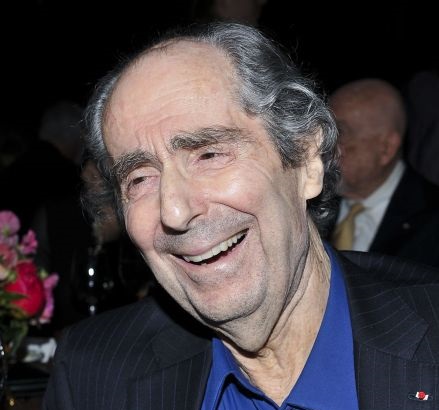

Portnoy’s Complaint was first published in New York in February 1969 and was an immediate sensation. Before it even hit the bookshelves, the film rights had already been sold to Warner Bros. for $250,000 USD.[10] The novel, by Jewish author Phillip Roth, is written in the form of a monologue delivered by the titular character Alexander Portnoy, who exorcizes the lurid details of his sexual life and guilty conscience to a Jewish psychoanalyst and ruminates on the frustrations of being a modern Jewish man. Much of the themes of the book likely went over the heads of non-Jewish readers who have not studied the peculiarities of this group of people—the overbearing Jewish mother and timid Jewish father, the lusting after non-Jewish women (“shiksas”), the pangs of Jewish assimilation, and the unique complications of being a Jewish minority in a Christian society. But the significance of the book as an honest presentation of the Jewish psyche (many consider Portnoy to be an author insert for Roth himself) was not lost on the more conservative Jewish leaders. Roth’s earlier works had caused a stir with the American Jewish community, who labelled him a self-hating Jew for failing to follow the dictum that Jews must never be portrayed negatively, only positively. Negative reviews of Portnoy’s Complaint appeared in Commentary magazine, the mouthpiece of the America Jewish Committee, and the religious leaders in the Australian Jewish community were similarly perturbed. Local Rabbis worried that the book was “very dangerous from a Jewish point of view” and “not good for the Jews.”[11]

Of Portnoy’s Complaint, Israeli philosopher and kabbalist Gershom Scholem declared that the book was more disastrous to Jews than The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and was “the book for which all anti-semites have been praying.”[12] With this critique, Scholem likely had in mind the numerous passages where Portnoy ridicules the “stupid goyim” or Portnoy’s cognizance that his lust for sleeping with gentile women (schtupping the shiksas) was almost a political act; by defiling their daughters, Portnoy was getting revenge on the WASP anti-semites who mistreated his father at work. Portnoy is, as E. Michael Jones writes, “a Jew right out of Mein Kampf,”[13] another Messiah who has come to liberate the gentiles, in particular the shiksas, from the binds of their Christian morality:

“To save the stupid shiksa; to rid her of her race’s ignorance; to make the daughter of the heartless oppressor a student of suffering and oppression; to teach her to be compassionate, to bleed a little for the world’s sorrows.”

Portnoy’s shiksas, each given a disparaging nickname (The Monkey, The Pilgrim and The Pumpkin), become the vehicle for his revenge-saturated sexual fantasies, but all three are eventually discarded when they fail to meet his expectations as sex objects. The archetype of the Jewish man indulging his fantasies—often revenge motivated—by having sex with the Christian girl, would become a common theme in the so called “golden age” of pornography, the pairing of Harry Reems and Linda Lovelace in the film Deepthroat being a famous example. It also played out in real life throughout the history of Hollywood, the #MeToo scandal being the latest iteration, where Harvey Weinstein and a cast of other famous Jews were caught out taking liberties with the shiksa on the casting couch. Aside from the screeds against gentiles, the most offending passages, and the ones read aloud the most in the obscenity trials, were undoubtedly the frequent descriptions of masturbation and the objects that accompanied Portnoy’s lewd ritual, from chopped liver to a sister’s item of underwear. Whereas Lady Chatterley’s Lover is embarrassingly written Pagan eroticism that is now quaint to read, Portnoy’s Complaint is fully fledged Jewish obscenity that has not lost its shock value. Even to a modern reader such as this writer, having been fully exposed to the depravities of sexual modernity, the masturbation passages are still viscerally repulsive and generally unpleasant to dwell upon.

In March 1969, an advance copy of Portnoy’s Complaint was sent to the Australian customs office by Tom Maschler, the Jewish literary editor of Jonathon Cape (Roth’s UK publisher), for approval to export the book to Australia. The book was identified for the prohibited list but conscious of the stir it caused in America, it was sent to the National Literature Board of Review for a final decision. Despite conceding literary merit, the board agreed that the presentation of obscene sexual themes outweighed any such merit and Portnoy’s Complaint was duly prohibited. Declaring the book to be “one of the most important literary works we have published in the last 10 years,”[14] Tom Maschler was outraged and vowed to fight the ban, turning to his colleague Graham C. Greene, the managing director of Jonathon Cape who had connections in Australia, to deal a death blow to Australian obscenity laws. Anti-censorship and sexual liberation ran in the blood of the Greene Family. Graham Greene was the son of none other than Hugh Carleton Greene, Director-General of the British Broadcasting Corporation from 1960 to 1969. With Hugh Greene’s support, his tenure at the BBC oversaw the arrival of the sexual and cultural revolution onto British television screens, decisions which led to his arch nemesis Mary Whitehouse’s campaign against the BBC. Greene was the BBC’s Berlin correspondent throughout the 1930s and it was here in 1936 that Graham was born, to the first of Hugh Greene’s four wives. Hugh Greene’s time under the National Socialist regime left him with a dislike of any form of censorship, equating Mary Whitehouse’s crusade against sex and obscenity on British television with the events of National Socialist Germany—comments for which Whitehouse won a successful defamation suit against Greene.

In Graham Greene and Tom Maschler, the Australian anti-censorship cause now had two heavyweights of the English publishing industry on their side and Greene began corralling the forces of the anti-censorship vanguard, seeking their advice on the specifics of the Australian situation. Greene voiced his criticism of Australia’s obscenity laws during his visit to Australia in October 1969, publicly threatening that Jonathon Cape would publish an illegal edition to flout the law. Various local publishers offered to run expurgated editions of Portnoy’s Complaint, but Maschler and Greene held to their aims (Maschler explicitly refused to allow an expurgated “Australian edition”), and saw an opening in a censorship system that was on increasingly shaky grounds. They found a willing publisher in Penguin Books Australia, who agreed to illegally publish the unexpurgated edition and struck a deal with Jonathon Cape for the publishing rights, agreeing to pay progressive royalties, depending on how many copies were sold. Following the model set by Fink and Co., 75,000 copies were printed in secret, reproduced via photo offset of smuggled copies, and by late August 1971, copies had been surreptitiously distributed to willing bookstores around the country. Word got out on August 30 and crowds of customers lined up to purchase a copy. Amongst them were the detectives of police vice squads.

In the ensuing chaos, the Australian government held firm in its support of the ban and legal action was taken against bookstores around the country, but defenders of Australian morals watched in dismay as the supposedly iron-tight response broke down around them in a mess of contradictory and disparate outcomes. Almost immediately the anti-censorship forces found a victory in the state of South Australia, where Don Dunstan, the then still closeted homosexual Premier (at the time still with his Jewish wife), announced that there would be no prosecution of the book in his state and that Portnoy’s Complaint would be free and legal to purchase for all adults. In Tasmania, the ban was upheld but no court cases ensued; in the state of Victoria, the book was declared obscene by a judge and the ban upheld; and in Western Australia, a trial centred around a bookstore in Perth owned by the Communist Party of Australia. The book was declared legal for sale on literary merit due to more liberal legislation in the state.

In Queensland, a court case saw a token fine imposed on another Communist bookstore, but the key battle came in New South Wales, Australia’s most populous state, and the location of the most important Portnoy trials. An impressive prosecution against bookstore chain Angus and Roberston was led by Jack Kenny QC, who outlined the impact a not- guilty verdict on the book would have not only on obscenity law but on wider moral virtues in the country, and attacked the concept of literary merit. Nevertheless, the defenders of Australian sexual mores found no respite, as two back-to-back court cases in NSW ended in a mistrial. Both juries were unable to come to a verdict.

Portnoy’s Aftermath

Following the second mistrial in NSW, Australia’s censorship system was in tatters. A third trial against Portnoy’s Complaint was out of the question. The country-wide mechanisms to police obscenity had been thoroughly broken. A different legal situation existed for Portnoy’s Complaint in every Australian state; in some it was still banned, and in others it was completely legal for purchase and possession. Or it was subjected to otherwise ambiguous legal outcomes that resulted in the book’s effective legalisation. As Mullins notes:

Where the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint figures most in the history of the end of book censorship is in its scale and scope. It was an unprecedented undertaking. In all the opposition to censorship in Australia, no other act of defiance was as bold. It was the first occasion where one book was used to test every channel of the Australian Censorship system.[15]

The Australian government, weary of the continual losses on this front, finally gave in on June 15, 1972, and Customs Minister Don Chipp rescinded the importation ban on Portnoy’s Complaint and a number of other previously proscribed books. Two final scuffles over obscenity ensued during the latter half of 1972, one over The Little Red Schoolbook and another over Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, banned since 1966, where a local publisher threatened to redo the tactics of The Trialand Portnoy’s Complaint with an illegal local edition. However, by this stage it was not only the censorship system that was in tatters, but also the governing Liberal Party of Australia. The election held in December 1972 swept the Liberal government out of office for the first time in 23 years, replaced by the Labor Party and Gough Whitlam as Prime Minister. A kindred soul to the anti-censorship cause and the political embodiment of the coming to power of the New Left in Australia, Whitlam promptly dismantled the censorship infrastructure under the Customs Act, removing all books from the importation ban list and removing powers from the Department of Customs to search for banned publications. The legal apparatus for dealing with obscene works shifted to the function of “classification” of publications based on age limits, and in 1974 the Whitlam government oversaw the introduction of a new federal classification scheme, which for the first time allowed pornography for sale and outright prohibited only publications which advocated for, or incited, crime, violence or the use of illegal drugs.[16] At the conclusion of the short-lived Whitlam Era in 1975, the concept of obscenity and the words “tendency to deprave and corrupt” had all but disappeared from the Australian legal system.

All told, Tom Maschler correctly identified the book as the ideal battering ram to bring down Australia’s obscenity laws. Just as Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker was the perfect mix of nudity and a “culturally important” holocaust tale that broke down the Catholic-based Production Code in Hollywood, Portnoy’s Complaint was the perfect mix of obscenity and celebrated Jewish literature that gave it all the leeway to exploit the fractures in the Australian legal system.

A Question of Literary Merit

Moving back to the Portnoy trials, the concept of literary merit was the common point of contention throughout all the criminal cases brought to trial in the Australian states. It all came down to whether or not Portnoy’s Complaint had literary merit, and if this merit overruled—where it had been successfully established—the obscene nature of the book. As Jack Kenny QC, counsel for the Crown during the NSW Portnoy trials outlined to the jury, the term literary merit has no accepted definition, being inherently vague resulting in it being utterly up to the interpretation of the numerous individuals professing to be literary experts who were called as witnesses for the defense.[17] In practice, literary merit is established as soon a book is published by a reputable publishing firm and given positive reviews by book critics in papers of record. In other words, Portnoy’s Complaint is literature for the same reason “Piss Christ” and Duchamp’s “The Fountain” are considered art—because it is in a museum, or in this case, because it was published. Once a piece of writing has passed these gatekeepers in the publishing firms and newspapers, any number of witnesses can be dredged up (as they were in all the Portnoy trials, and similar obscenity trials in the UK and USA) to declare a work as having literary merit. There were as many different interpretations of the term offered during the trials as there were people declaring to be literary experts. When it comes to Portnoy’s Complaint then, who were these gatekeepers?

By now the answer should come as no surprise to readers. It was published by Random House, Jewish Chairman and co-founder Bennet Cerf personally presenting Roth with a contract and an advance payment,[18] and the book received early positive reviews from Jewish critics Josh Greenberg at the New York Times, Albert Goldman at Life magazine and Alfred Kazin of the New York Review of Books. Portnoy’s Complaint struck a deep chord with second- and third-generation Jewish immigrants in America, who at the time were becoming entrenched in the publishing houses and in the wider literary culture of America. It was a time when the older concerns about how Jews were to assimilate into America were subsiding to the realization that American culture itself was becoming Jewish. As underscored by Edmund Connelly:

Roth began writing in the midst of what we can think of as the “Jewish American literary onslaught,” as Jews practically took over publishing fiction in America, and Jewish authors shouldered aside non-Jewish writers. Any English student at an American university from 1970–2000 or so would be familiar with the names: Abraham Cahan, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Joseph Brodsky, Henry Roth, Bernard Malamud, Chaim Potok, Saul Bellow, E.L. Doctorow, J.D. Salinger (half), Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag, … Erika Jong, Cynthia Ozick and so many others.[19]

The idea of literary merit, if it ever had a concrete definition, comes from a time before Jews took over the reins of the major publishing houses and the direction of American (and therefore Western) culture; a time when it could be expected that the people at the helm of publishing houses would hold the fort against obscenity and not allow blatantly obscene works to be published.

Bibliography

[1] P. Mullins 2019, The Trials of Portnoy, Scribe Publications, Australia.

[2] For a while seditious works were also prohibited in Australia.

[3] Mullins, op. cit., p.30.

[4] The defendant Wald was Jewish abortionist Louis Wald, a practitioner at the Heatherbrae Clinic in the suburb of Bondi, at the time the largest illegal abortion clinic in Australia.

[5] Mullins, op. cit., p.40.

[6] Mullins, op. cit., p.45.

[7] High Court of Australia, Crowe v Graham Judgement, retrieved from: https://staging.hcourt.gov.au/assets/publications/judgments/1968/078–CROWE_v._GRAHAM–(1968)_121_CLR_375.html

[8] Mullins, op. cit., p.147.

[9] Mullins, op. cit., p.32.

[10] Mullins, op. cit., p.62.

[11] Australian Jewish News, Portnoy—A Series of Complaints, 30 September 1970, p.11.

[12] Mullins, op. cit., p.64.

[13] E. Michael Jones, 2008, Chapter 30 The Messiah Arrives Again. In: The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit, Fidelity Press, USA, p.974.

[14] Mullins, op. cit., p.69

[15] Mullins, op. cit., p.261.

[16] Commonwealth of Australia, 2011 Review of the National Classification Scheme: achieving the right balance, Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, p.30.

[17] Mullins, op. cit., p.197.

[18] Ibid., p.62.

[19] E. Connelly, 2018 ‘Harvey Weinstein: On Jews and the Shiksa’, The Occidental Observer, retrieved from: https://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2017/10/18/harvey-weinstein-on-jews-and-the-shiksa/